The Darcawi Holy Man of Marrakech. Front and back prior to the treatment.

More than a conventional watercolour, The Darcawi Holy Man of Marrakech, by Josep Tapiró (Reus, 1836 – Tangier, 1913) is a water-based painting, very richly worked, that doesn’t leave you indifferent. The circumstances, however, had led it to a such a deficient state of conservation that the aesthetic potential and technical quality had become lifeless. Its inclusion in the museum and the imminent monographic exhibition dedicated Tapiró meant that it was the ideal occasion to tackle the restoration.

Just the removal from the frame, the numerous oxidation stains and two blue strips on the sides of the clear background made us suspect that something had happened, beyond just the aging. For this reason a prior study was required that would give us answers as to how Tapiró had painted the watercolour and what had happened to it over the years.

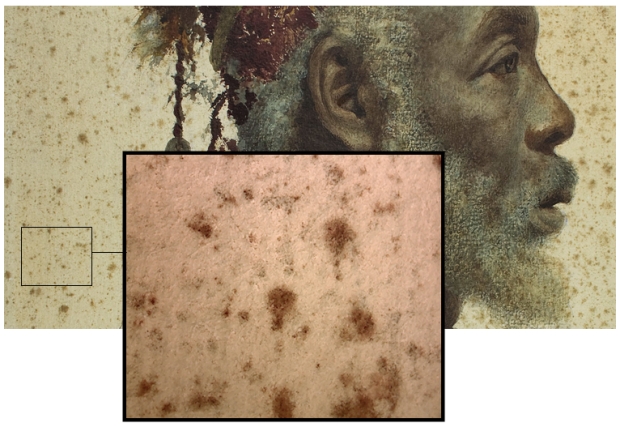

Foxing spots seen with ultraviolet light and transmitted light.

Detail of the blue colour that is conserved on the sides of the work.

The effects of a previous intervention blanching, the excess of light and acidity

Different analyses (measurements of pH, chemical analyses of the pigments and of the paper and the examination with ultraviolet light) corroborated what we suspected with the naked eye, that the background should have been as blue as the margins, and that it had become discoloured, who knows if it was after a chemical treatment for improving the aesthetics. The blanching treatments of the paper, with products such as bleach or something similar, were very common among restorers in the last century. The problem is that they could leave very reactive residues, capable of continuing to act over time. If we add to this an excessive exposure to light of the treated parts and an environment of the work of acid and damp, the discolouring effect could continue and the spots could appear again, more violently and darker. This was the main cause that explains why a watercolour done with such good quality materials was now stained and with a whitish background.

Detail of the foxing spots.

The restoration process. Treatments prior to the damp cleaning

First of all, it was necessary to removed the remains of the gummed paper, which at another time had been used to subject the work to another old mounting.

Removal of the gummed paper from the back, with rigid aqueous gel, PhytagelTM.

The next step consisted of reducing the intensity of the surface stains on the back, especially those which were on a layer of starch glue, that covered the painting. To define the exact point on which it was necessary to act, it was very useful to have a perforated template, with different sized holes, which allowed us to adjust to the diameter of the stains.

Cleaning stain by stain, with methylcellulose gel, rubber and scalpel.

Detail with the first results.

Damp cleaning by steam and absorption

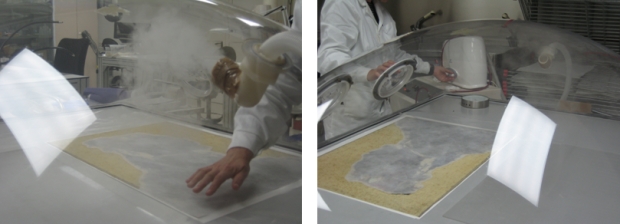

In works on paper, the effective way of dissolving impurities and acids tends to be by cleaning with water. As this operation places at risk the watercolour and gouache, two techniques used in the portrait, we have used water but only in the form of steam. The steam penetrates the paper with smaller particles as if it was done in liquid state. This is the key to moisturising and conserving the solidity of the painting.

Once the work is impregnated, we put it on a suction table and in contact with another paper, wetter and more absorbent. Slowly, the impurities were dissolved and the residues moved from the work to the contact paper. We repeated the procedure with slightly alkalized water vapour, so as to reduce, even more, the intensity of the stains and to provide an alkaline reserve.

Chamber of induced steam. Cleaning and de-acidification, by contact and suction, once the work is damp.

Although this is the most delicate operations, it is also the one that provides more benefits, given that it leaves the paper chemically stable and improves the luminosity of the watercolour.

Images of the end of the intervention, with diffused light (left) and ground light (right).

Now that The Darcawi Holy Man of Marrakech is once again on display in the rooms, I am thinking about the way in which Tapiró painted and how he achieved similar effects to oil on canvas, with water colours on paper. It is true that the technical complexity that this requires hasn’t facilitated its restoration, but for those of us who have had the opportunity to participate, it has been quite a discovery.

Restauració de paper