Francesc Quílez

It goes without saying that due to its characteristic subjective nature aesthetic appreciation generally gives rise to unexpected responses that often alter our established perceptions and prejudices. In the case of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya’s collection there is a painting, Public Exhibition of a Picture, by the painter Joan Ferrer Miró (1850-1931), which calls into question the opinion and the judgment of the experts, since the enthusiasm it arouses among the public is at odds with the scant canonical recognition that the work has merited among art historians.

Portrait of Joan Ferrer i Miró, Pere Borrell. Private collection

Although we may find it surprising, since it is merely a work by a local artist, and therefore little known outside Catalonia, it is one of the most consulted works in the Modern Art collection on the museum’s webpage. This indicator enables us to quantify and appraise the attraction the painting exerts on the nonprofessional public.

Without intending to be controversial, in my case I continue to find it baffling that a composition, apparently so banal, which radiates rather too much sugary sentimentality, arouses such an empathetic response and has become one of the most valued creations of all those that can be seen on the long tour of the rooms of the Museu Nacional’s permanent collection.

On the following pages I shall attempt to decipher some of the reasons that, in my opinion, could explain the gulf between the positions defended by public opinion and the critics. Perhaps, by trying to understand some of each side’s motives and reasons, I may help to close the gap that tends to separate both sides. Reality, even though we may refuse to accept it, is stubborn; it often tears down the most elaborate theoretical constructs and demolishes all beliefs and dogmatic principles.

A work that transmits a very “good vibe”

To begin with, to enlarge on the idea that I expressed above, one cannot underestimate an incontestable fact: the majority of people who view the work tend to extol it, to consider it an attractive, praiseworthy composition. In short, it is a painting that people usually like a great deal. Generally speaking, it generally arouses a very positive emotional reaction because it is pleasant to look at and above all because it transmits a feeling of calm and tranquillity and produces a very beneficial psychological effect. It is what we might call, in colloquial language, a picture that transmits a very good vibe. The subject is neither disturbing nor unsettling. On the contrary, in general terms the dominant atmosphere is very satisfactory, balanced. The principle of harmony between all the parts is sought, with a mise-en-scène that combines the panoramic view with the liking for detailed description, captured with care and seeking the aestheticist effect, without committing the sin of excessive colour, artificial embellishment or a tendency to cultivate a disproportionate virtuosic preciosismo.

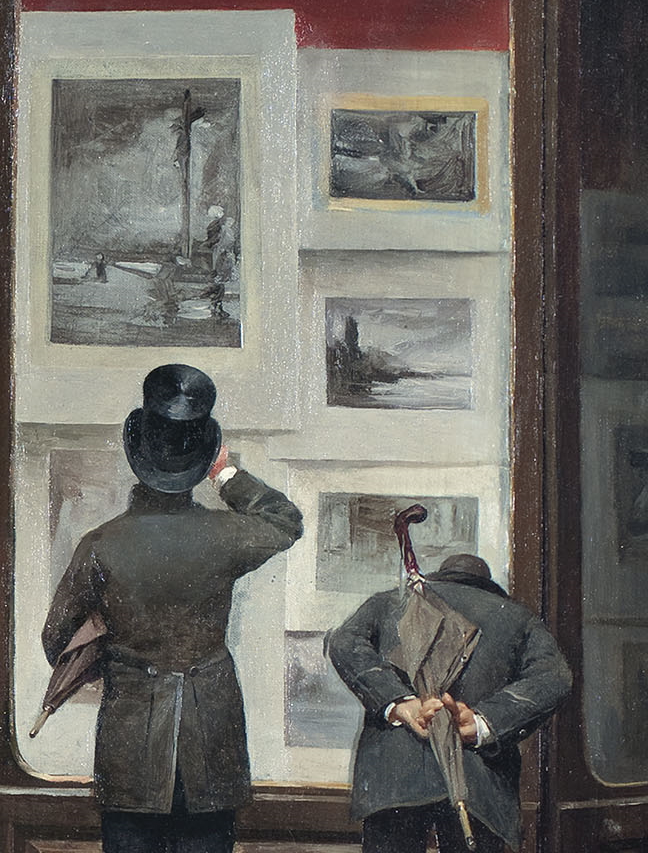

Public Exhibition of a Picture, Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

In fact, I believe that what the observer appreciates the most is the picture’s appearance, so natural. Although it is merely a deceptive feeling, the fact that the painting reflects reality takes us close to a model in which nature, despite having been embellished, retains a feeling of authenticity, of poetic truth in which the fictional game requires the acceptance, on the part of the viewer, of visual conventions that under no circumstances eclipse or take anything away from the end result. The trompe l’oeil that the painted image forces upon us requires a predisposition, an attitude in which it is necessary to allow ourselves to be captivated by the deceit of the three-dimensionality of the spaceand obliges us to distinguish reflection, which involves an intellectual exercise, from the more automatic, more instinctive response, considered a more intuitive and spontaneous urge.

This kind of reaction entails the need to eschew the influence of the visual baggage, to observe things disregarding the way in which logical thought works. In this respect, looking requires of us an attitude free of prejudice, it obliges us to jettison all the formative, cultural tools that limit the scope of our vision and do not allow us to see the world through more virginal, less contaminated eyes, since pre-existing experience continues to weigh too heavily in our attitude to things.

In any case, it would be too pretentious, on my part, to speculate about the reasons why a work, apparently so simple, far removed from the parameters of sophistication and complexity, has become such an important piece of the popular imaginary, so much so that it has become one of the most iconic works in the Museu Nacional’s collection. At the very most, what I can do is exercise my imagination and attempt to decipher some of the iconographical and visual clues that, in my opinion, might explain the aura that surrounds the painting. This kind of analysis will help us to better understand the context in which it was made, get to know its stylistic and formal characteristics, ponder the value and the merit of its contributions, and penetrate the cultural ins and outs, the originality of a motif and an iconography not really touched upon by the Catalan painters of the period.

Nevertheless, it must be said that, in general, the viewer’s positive appraisal does not usually take any of these historical aspects into account. Nor does their judgment appear to be conditioned by any of these characteristics that we might call meta-literary, which lie hidden beneath the layer of a supposed iconographical superficiality and simplicity.

The capturing of an instant in a world in apparent equilibrium, a magnet for viewers

In this respect, the image is highly persuasive, it evokes an instant, capturing a moment in which the action in the scene seems to be frozen. The protagonists, actors occupying the scene, have been captured standing still in a break from doing different things. One of the painting’s virtues is unquestionably its power to magnetize, because the characters act naturally, without adopting artificial poses. We could say that they had been surprised as they were strolling along the street, doing everyday activities and living immersed in a genuine reality.

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

To achieve this goal, the painter uses visual resources with skill and intelligence, because he projects a familiar world, a fragment of the reality that takes place in the streets of a big city – whose identity is unknown – and he does so without frills or unnecessary embellishments that could distract the viewer. This is not an obstacle to creating a balanced artefact, in which there is a highly studied mise-en-scène and an effective combination of light, colour, atmosphere, figurative elements, a balanced setting, creating a very harmonious and balanced whole. The end result is effective and in the conceptual approach one perceives the possible influence of a technique, photography, which the painter uses as a model seemingly to gain inspiration in order to copy the photographer’s behaviour, the view from a camera lens that captures the frozen instant of a fragmentary reality. Although we do not know whether Ferrer Miró was familiar with photography, it cannot be denied that the painting owes a great deal to it and its aesthetic seems to show signs of the impact that the emergence of photography had on the development of painting.

I mentioned above that one of the possible reasons for the pleasure and the attraction that this image aroused could have been due to the fact that it presents a world without conflicts, without inequalities, in which the social classes put their differences to one side and are able to live together harmoniously. Talking of the social classes, it is clear that the painting’s main protagonist is the bourgeois gentleman, an archetype of that class and, by extension, the affirmation of a worldview that transmits a particular scale of values. These include the cultivation of practices and pastimes in which art and the consumption of artistic products emerges as a novelty that confers prestige and fame in equal measure.

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

As well as reflecting these more intangible values, to which I will refer again below, we also discover other aspects that help to create a stereotyped image of this social type. The clothes worn by these figures evidently enable us to appreciate their liking for the latest fashions, the wish to foster elegance, refinement, luxury and all the elements that announce a person’s high purchasing power. These outward signs, the hat, the Cuban cigar and the fine clothes, become icons, badges, of a social class that shows itself to be proud of belonging to a group that exhibits its demeanour and distinction unabashedly, flaunting its identity and its upward social mobility.

Epiphany Eve, Joan Ferrer i Miró. Private collection (left); Public Exhibition of a Paicture, Joan Ferrer i Miró. Private collection (right)

Looking at Paintings, Joan Ferrer i Miró. Private collection

All this visual repertoire ties in with pictorial language in which elements stand out that confirm the role played by a bourgeois clientele that likes to see itself reflected in artistic compositions that become sumptuary goods, objects destined to adorn the interiors and lounges of bourgeois houses. This style, to which Ferrer Miró’s work belongs, can be identified with the movement known as narrative painting, which emerged in the political period of the Bourbon Restoration and, in the case of the city of Barcelona, the setting for the famous novel by Narcís Oller (1846-1930), La Febre d’Or (Gold Fever, 1890-1892), reached its maximum apogee in the 1880s. The year 1888, when the Universal Exposition of Barcelona was held and the painting we are discussing was made, constitutes the high point of the success of this type of painting, in which the work of art contains an ideological message and becomes a vehicle for transmitting the system of values of the ruling class.

The painting is also a protagonist

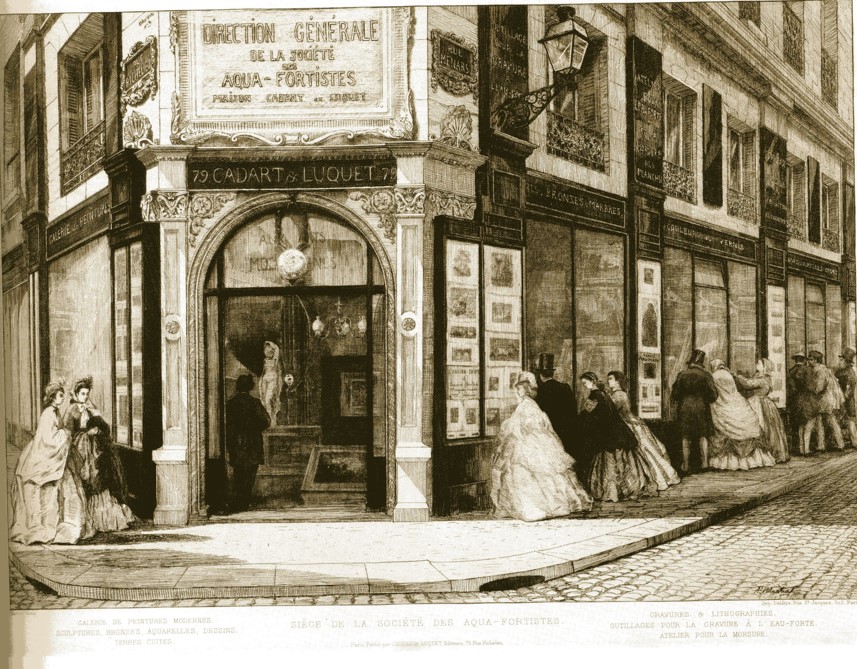

Le Siège de la societés des aquafortistes, Adolphe Potemont Martial

With respect to the content, I wish to broaden my interpretation and talk about some other aspects, which I have mentioned already, in greater detail. To begin with, the painting conceals a reference to the classic cliché of the painting within a painting, the famous expression that was coined by the historian Julián Gállego; that is, the painting takes a self-referential look, since the main motif of the composition, the core of the narrative, is the painting, and more specifically, the public exhibition of one. Far from persisting in one of the habitual commonplaces – alluding to the picture as the expression of a high level of culture – in this case it is rather a way of advocating both the importance of the artistic phenomenon and all that is meant socially by the appearance of an art market. Besides the commercial value it gives rise to this also generates new dynamics, including the appearance of new rites, such as that of the pastime of being able to enjoy the possibility of amusing oneself by looking at the work of artists. This latter activity undoubtedly leads to the appearance of a new liturgy that entails a substantial change in the process of appreciation. It goes from being a private activity, exclusive to elites, dealers, or customers who privately commission works, in which the scope of the aesthetic pleasure is limited, to the socialization of an activity that opens the doors to an experience that is more democratic and more available to everybody, with a supposed inter-class horizon.

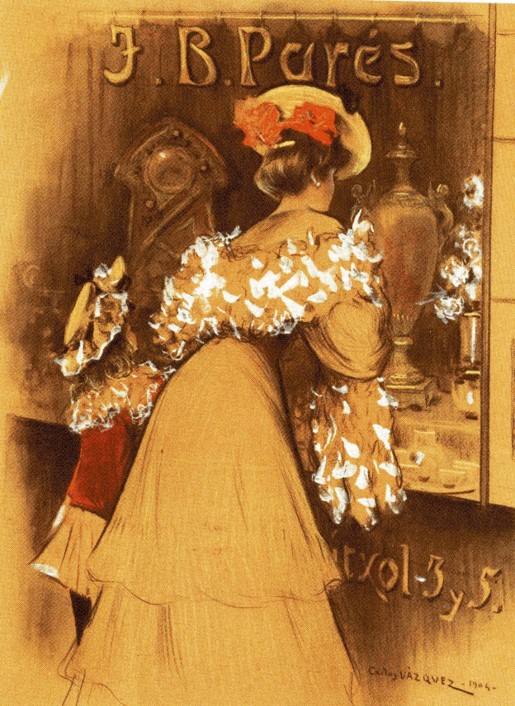

Original poster for the Sala Parés. Carlos Vázquez Úbeda. Private collection

The proof is that, as can be seen in the picture, the act of displaying the painting arouses unusual interest, high expectations among the people looking at the work through a window. We however are unable to share in the experience, since these same figures act as a barrier and prevent us from knowing the identity of the real protagonist, its physical and thematic characteristics. We can only guess that it is a large-format work, because we can see part of a large frame that, moreover, we sense is very ostentatious.

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

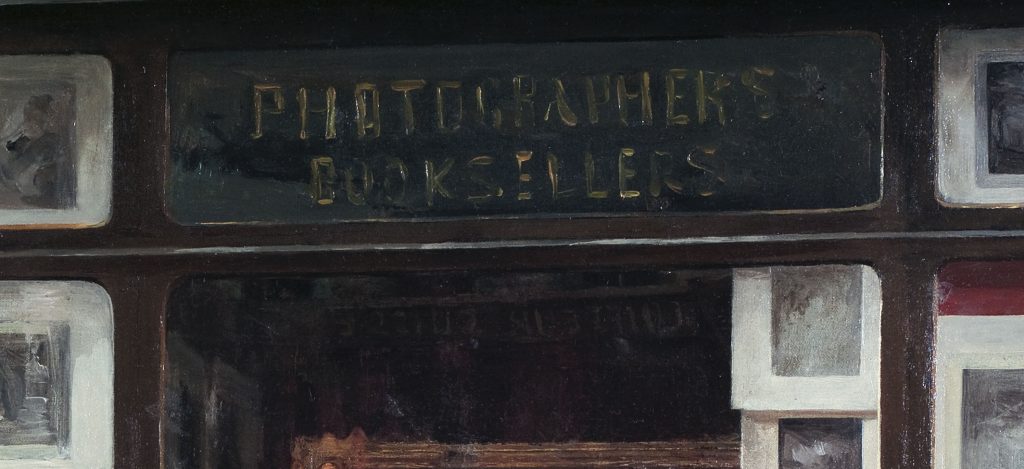

The group of people is looking intently at the gallery window, which also includes a varied representation of artworks, most noticeably a large number of prints, a more economical and affordable kind of artwork. In fact, the sign, written in English, that appears at the top of the window tells us that it also sells books and photographs; it is obviously a sort of second-hand shop, or an antiques shop, selling all kinds of things.

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

With respect to the protagonists, the painter is evidently interested in depicting a mixed group of people, in which he finds room for different social classes. Among them we see a woman with a baby, stereotyping motherhood and objectifying the social role of women; a young man who personifies curiosity and the desire for learning and knowledge; finally, we also see a painter, since we recognize him by the implements he is holding in his hands (a painter’s easel, of the kind called campaign, a paint box, a rolled-up canvas and a stool). Although – and this is not just speculation – who knows, he could be an apprentice in the process of being trained who admires other colleagues who are already enjoying the opportunity to be able to exhibit their creations, an opportunity to which he also aspires; or he could be a painter who is starting out in his career and aspires to be equally famous.

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

The democratizing role of the art gallery / The importance of shop windows

Public Exhibition of a Picture (detail), Joan Ferrer Miró, circa 1888

Art galleries played a very outstanding role in this historical process of democratization of the aesthetic experience, since they acted as the intermediary between the artist and the public. Moreover, in this case the gallery opens its doors, metaphorically speaking, to the people strolling along the streets who, spellbound, watch the presentation of new paintings as if it were a show. To strengthen this function galleries had strategic resources, among them the shop window, which made it possible for things to be seen from the street outside without it being necessary to enter the place. It contributed to the task of dissemination by allowing the principle of transparency to triumph over concealment. In this way, the fact of prying, of satisfying one’s curiosity without being dismissed as a busybody acquired a legitimacy that it had previously lacked. By way of the glass display case the shop window even made it possible to break down the barrier that separated the public from the private realm. In this respect, it was not even necessary to open the door to desecrate a private space, because the gallery owner, who wished to advertise his wares, preferred to exhibit them, to bring them closer to an extensive selection of passers-by ranging from onlookers and enthusiasts to connoisseurs or experts.

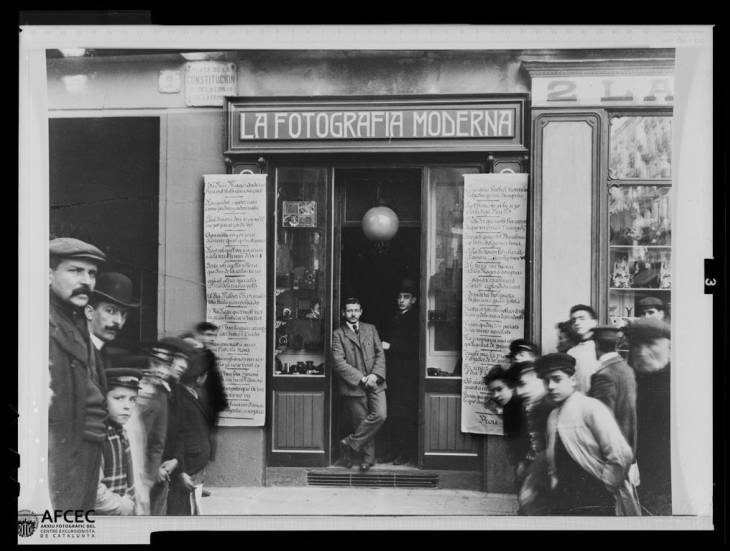

La Fotografia Moderna Shop. 1910-1915. Archive of the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya

Unquestionably, the shop window, together with the aisles inside – conceived, as Walter Benjamin rightly said, as veritable underground cities, built artificially, in the manner of meanders or tributaries flowing into a wide river, formed by a network of overcrowded streets, in which an anonymous multitude was moving in the direction of the current – constituted one of the great cultural contributions of the nineteenth century. In the end, unlike outdoor public places, the functioning of this submerged city was not determined by natural laws, as the opening times were not governed by daylight, but they took advantage of new inventions, like the one represented by the installation of gaslight. All these new conditions crystallized in the appearance of fantasy places, artificial paradises that helped to consolidate historical optimism and faith in the transformative capacity of mankind. In itself, this set of ideas was a landmark in the process of eradicating the ideal of nature. Nature ceased to be contemplated as a model to be followed and became an adversary that had to be subjugated. These transformations indubitably set the pace and marked the life of modern cities that worshipped technological progress, thanks to which they began to catch sight of the possibility of successfully materializing a futuristic utopia.

Looking in the Window, Manuel Cusí Ferret. Private collection

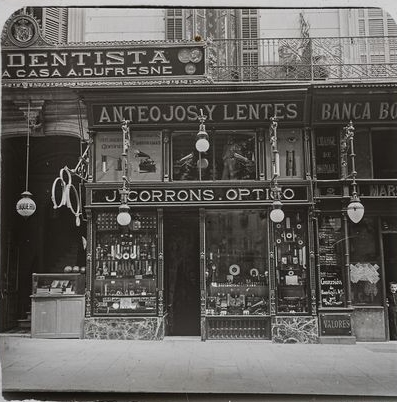

In the case of Barcelona, on a lesser scale and without ever reaching the level of propagation that took place in the Paris of the grand boulevards, in the last decades of the nineteenth century shopkeepers imitated the same model and plotted a strategy to cater for an increasing demand for artistic goods. In this they met the needs of a bourgeoisie that aspired to live comfortably without renouncing the adornment of interiors that were decorated with furniture, mirrors, ceramic panels, paintings, bibelots, and so on. In this respect, the city experienced increasingly transformative activity that, logically, also affected the changes in the habits of consumption and the creation of commercial arteries. This was the case of, among others, Carrer Ferran, in which the shop owners came up with ideas for catching the eye of potential consumers. Many of these shops did not hesitate to incorporate the shop window as a necessary resource for showing customers the wares, for opening up to the outside world, arousing curiosity and stimulating the desire to purchase things.

Shop window of the Corrons optician’s. 1900. Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

The so-called Gold Fever was the best breeding ground in which businesses could flourish and meet the ostentatious sumptuary needs of a class with high purchasing power.

It is moreover obvious that the aestheticism of these shop windows helped to reinforce a system, capitalism, that underpinned its existence using a type of stratagem in which artistic goods appeared as a lure, a decoy to grab the passer-by’s attention. In actual fact, in the medium term they heightened the process of social alienation, since the owners played with the fiction of the closeness of objects that seemed to be within everyone’s reach, when in reality they were only affordable by the minority that had the necessary purchasing power to buy them. In this respect, nineteenth-century aesthetics widened the gaps between the social classes, as it incentivized the economic value of beauty to the detriment of its formative or social dimension. In any case, we must not make the mistake of lessening the transformative capacity of art and increasing the influence of political control of the state that could have been seeking ideological indoctrination or paternalism aimed at neutralizing, through subjection, the power of rebellion contained in the artistic experience.

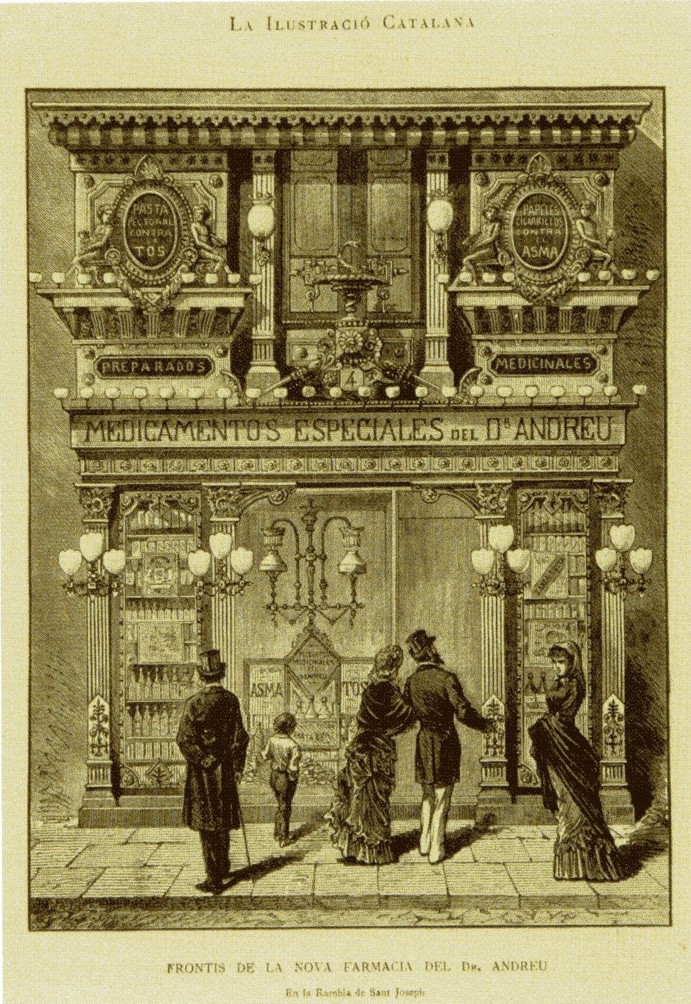

Façade of Doctor Andreu’s new pharmacy. La I·lustració Catalana, Barcelona, 1882

This last reflection is interesting because it describes the existence of a supposedly public model, when it was in fact private, as it turned works of art into merchandise, products whose ultimate purpose was to be bought and which, therefore, legitimated the principle of private property. It is no less true however that in spite of its obvious limitations, and due to the absence of public services, for example the nonexistence in many cases of heritage facilities – in short, public museums addressed to cultivating aesthetic education – the appearance of these private galleries helped to raise the public’s awareness of the important social role of art. In that period, the last third of the nineteenth century, a number of art galleries flourished in the city of Barcelona, the best known and most popular one being the Sala Parés, founded in 1877 by Joan Baptista Parés (1848-1926). More modest in nature, we cannot forget the appearance some years earlier of the gallery founded by Francesc Bassols in Carrer Escudellers. In the same year it opened, 1875, the street began to enjoy the advantages of gas lighting. Even so, the previous model was in opposition to a second one, that of the public museum, the heir to the enlightened tradition based on other principles and values. In some ways, the latter aimed to eradicate the market value in order to focus all the interest on the social value of art objects.

Public Exhibition of a Picture in context

The above considerations help to frame and understand the context in which a painting such as Ferrer i Miró’s was created. Beneath this layer of superficiality, of visual appearances, very effective in artistic terms, in which a moving iconic image predominates, we discover the existence of an entire social and ideological network, in which the practice of art occupied an important place, since it performed a function of legitimization that contributed to rearming the interests of the ruling class.

The proof that the painting came to satisfy the dominant criteria of taste is that its maker won a prize after presenting it at the Universal Exposition of 1888. The gold medal, awarded for the work, attests to its adaptation to the standards, the conventions, the models and the subjects that gained the approval of critics and public alike. In this respect, we cannot forget the success of a painting of which a second version was made in 1890, with some variations and in a larger format, and which established the painter as a conspicuous representative of the narrative genre; a genre that was a mirror in which the bourgeoisie could look at itself and be comforted upon seeing its reflection.

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats