Camposanto monumentale, Pisa. Foto: Kaho Mitsuki, via Wikimedia Commons.

Restorers, but also architects, engineers, physicists and chemists, conservators of collections, politicians, members of the church and managers, participated in the latest congress about European cathedrals which is held annually in Pisa and that, in its fourth Edition, was dedicated to the conservation of pictorial heritage. Organised by the Opera della Primaziale Pisana, the emphasis was placed on mural painting by taking into account, on the one hand, the extraordinary heritage of mural painting from all periods conserved in Italy, and, on the other hand, the process of restoration of the frescos of the Camposanto de Pisa – an exceptional experience due to their complexity and their reach that we will comment on below. The promoters of the event understand in this way that the restoration is a critical act and an ideal methodological moment for the recognition of the work of art in all its dimensions, just as the most famous theoretician of the discipline, Cesare Brandi wrote in the 1950s.

Conference brochure.

Experiences presented (among others)

■ the restoration of the frescos of the high basilica of Assisi after the earthquake

■ the experience of the frescos of Luca Giordano of the Escorial and that of the Renaissance angels of Francesco Pagano and Paolo of San Leocadio which were discovered under the Baroque vault of the greater chapel of the cathedral of Valencia

■ the restoration of the paintings in the cathedrals of Florence, Orvieto, Basel, Strasburg, Cologne, Peterborough, and Albi

■ the intervention in the cycle of mural paintings found in the lower church of the cathedral of Siena, that some people have already called “the discovery of the century”

■ the pictorial series of Giotto in the Santa Croce of Florence

■ the exemplary maintenance of the celebrated cycle of the chapel degli Scrovegni de Pàdua

■ the changes planned for the air conditioning and illumination of the Sistine Chapel

Only two invited museums went, the National Museum of Belgrade (Serbia), that possesses an important collection of copies of medieval frescos, and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, which has conserved, since the beginning of the 20th century, a series of original mural paintings from the 11th and 12th centuries.

The restoration of 1,500 m2 of pictorial space in the Camposanto de Pisa

The talks about the various case studies will be published later on in the form of proceedings, as was done in previous editions, but I would like to highlight the work done in Pisa in the nearly 1,500 m² of pictorial area of the Camposanto, an extremely important monument and barely known by the tourists, who do everything they can to be photographed alongside the famous leaning tower, but these tourists rarely visit the immense Gothic cloister of marble, just a few steps away. The Camposanto was originally dedicated to the worship of the dead and in the 19th century was to become one of the first public museums of Europe. The galleries were full of graves and mausoleums with sculptures from different periods and interior walls which were decorated with frescos from the Trecento and from the Quatrocento, by painters such as Buonamico Buffalmacco, Andrea Bonaiuti, Antonio Veneziano, Spinello Aretino, Taddeo Gaddi, Piero di Puccio and Benozzo Gozzoli.

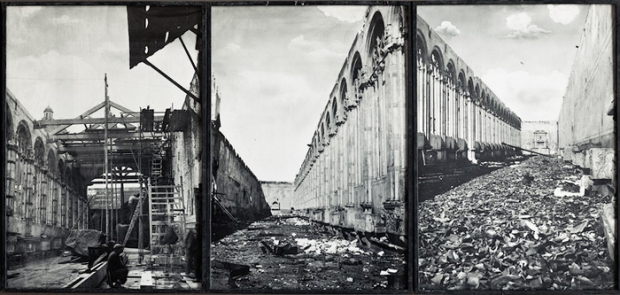

State in which the monument remained in 1944. Photo Foto Art in Tuscany.

Towards the end of the Second World War, in the summer of 1944, a grenade fell in the cloister and caused a fire that lasted for three days. As a result, this led to the destruction of the roof and caused irreparable damage to the paintings on the walls. A few years afterwards, the remains were removed, and were transferred to a new support and were cleaned so as to collocate them again on the walls with the roof reconstructed. In the post-war years it was difficult to find some materials and as a rigid support for paintings fibre-cement which contained asbestos was used, a product that was later to be shown to be carcinogenic.

Leonetto Tintori, director of the restoration works of the Camposanto Monumentale, Pisa, 1949. Photo: Laboratorio Tintori.

The current restoration macro-project didn’t begin until 2008, which was foreseen to be completed in 2016, and that has included a new removal of frescos to eliminate and replace both the existing support, as well as the adhesive that fixed the painting. For this operation micro-organisms have been used, specifically some “trained” bacteria for eliminating a certain substance, in this case the calcium canseinate that no longer had adhesive powers. The restoration process has been complex, full of innovations and exemplary due to its interdisciplinary methodology, which has mobilised many professionals from technical, scientific and humanistic fields, and which has been closely followed internationally within the ambit of cultural heritage.

In 2010 the Museu Nacional invited some of its protagonists to Barcelona for them to explain the case to the professionals in a seminar and now the people of Pisa want to get to know the Catalan experience more closely: the work of the removal and transfer of some paintings also with calcium canseinate in which it hasn’t been urgent to intervene in such a drastic way due to the fact that they have been conserved in a museum.

Conclusion

Throughout the Congress the worry was manifested regarding the reduction of resources, both economic and human, and in the Italian case, the political rigidity in matters regarding the contracting of staff and also due to the lack of autonomy in terms of deciding on the themes for study and research. Everyone expressed in one way or another the difficulties and the responsibility that the interventions of restoration signified for the professionals and the need to share and discuss results in a collective and open way, so as to improve and enrich the new proposals.

Italy has known how to protect the work of conservation-restoration and has been able to export it in a magnificent way all around the world, and it has done so well while obtaining a deserved reputation, influence and prestige. In this field, we still have a lot to learn from Italy.

Related links

Il restauro del Camposanto monumentale di Pisa danneggiato durante la seconda guerra mondiale (PDF)

Conservació preventiva i restauració