Francesc Quílez

This last year, those of us who love the work of the painter Marià Fortuny have been very fortunate. Two temporary exhibitions have given us the chance to contemplate the talent of one of the finest nineteenth-century European painters.

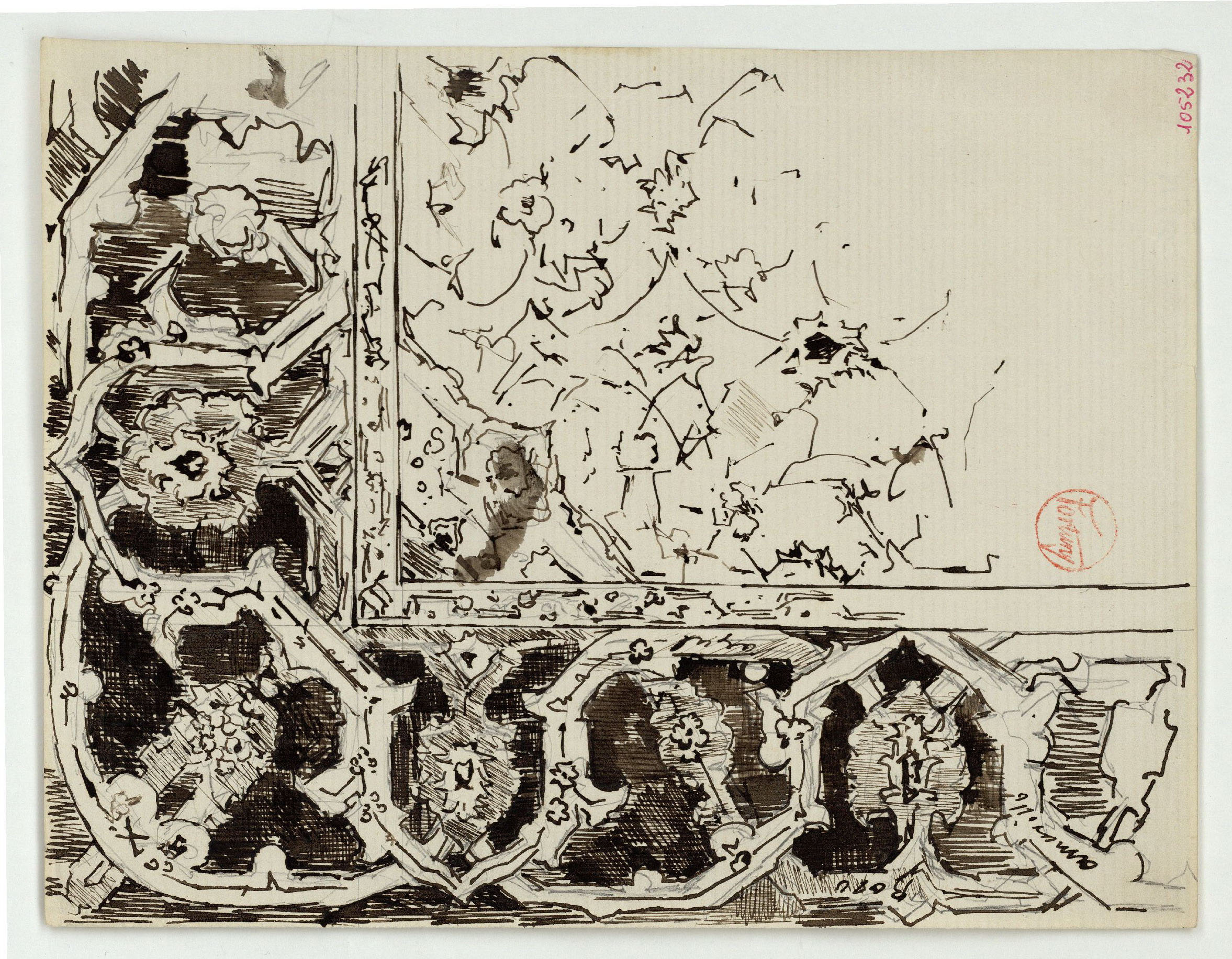

Marià Fortuny, Detail of a Muslim-style tapestry, circa 1870-1872

Since November 2016, the show A Time for Daydreaming. Andalusia in Fortuny’s Imagery has been travelling around Spain, and it is currently in Seville, after visiting Granada and Zaragoza. Produced by our museum, Obra Social ‘’la Caixa’’ and the Board of Trustees of the Alhambra and Generalife, the exhibition presents virtually all the work the artist did in Granada, giving pride of place to the extraordinary collection of drawings from this period of activity, many of them unpublished, that are conserved in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

The recent inauguration, in the rooms of the Museo Nacional del Prado, of a retrospective show of his work, constitutes a magnificent opportunity to revisit many of his most emblematic compositions, which continue to elicit an admiring response.

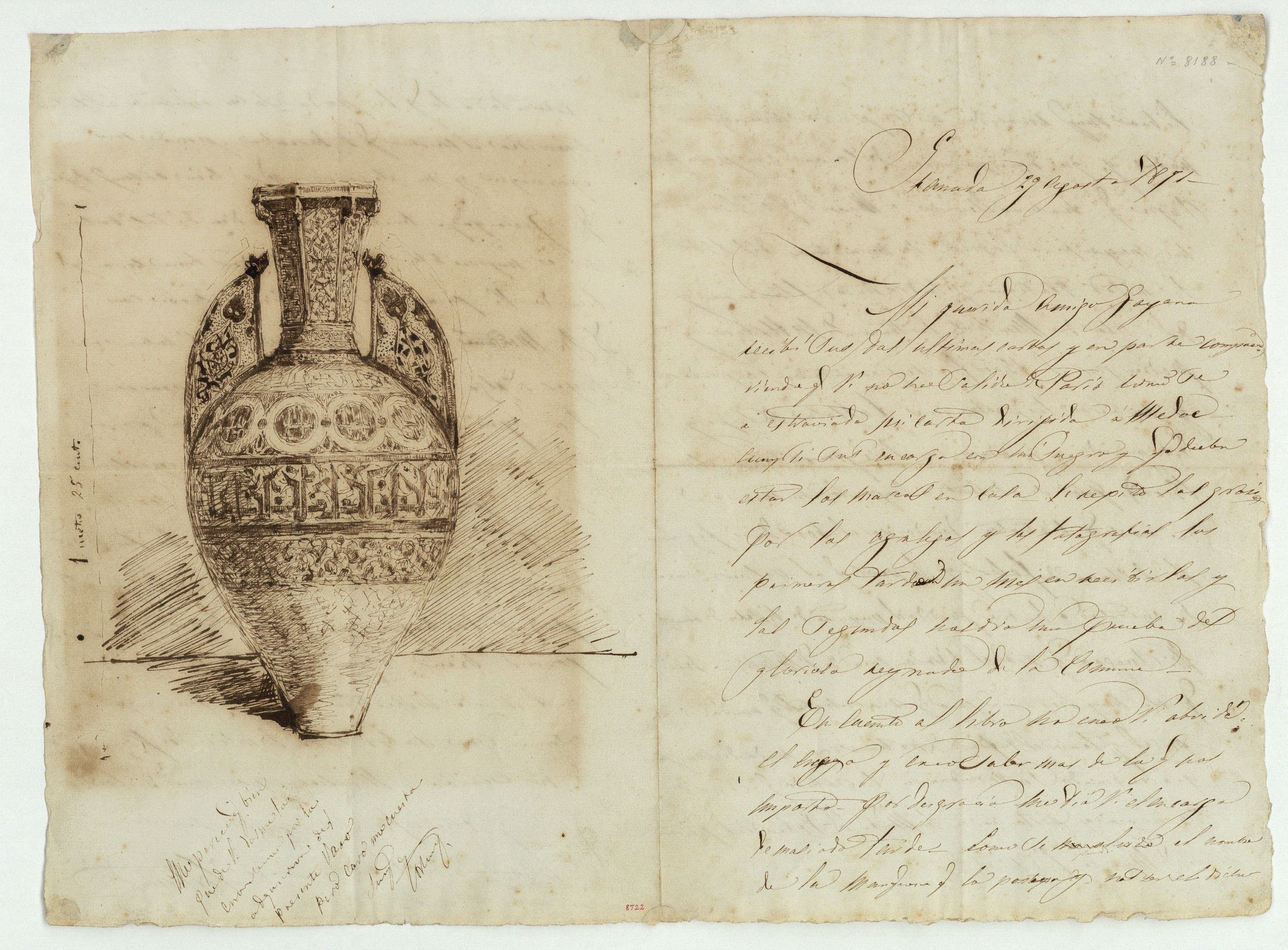

Marià Fortuny, Muslim-style vase, 1871

In the case of Fortuny, far from undermining the power of his seductive poetry, and despite their implacable hoary anachronism and their dangerous kitsch leanings, the historical circumstances, the antiquated nature of a nineteenth-century past enveloped in a whiff of outmoded perfume, surrounded by powdery wigs or luxurious, gleaming frock coats, in some way constitute an anecdote or a scenographic resource. In other words, despite this old-fashioned veneer the validity of his work is indisputable, and its modernity is also beyond doubt.

The proof of this is that Salvador Dalí always interpreted Fortuny’s creativity as modern, and he even expressed an open adherence to many of his aesthetic principles.

Painter and antiquarian, the two sides to Marià Fortuny

The painter’s vocation for being an antiquarian is common knowledge. The urge, which became an authentic passion, for collecting objects marked his life as a man and an artist profoundly. Indeed, an unbreakable link was forged between the two facets and neither of them could be understood without taking the other one into account.

Marià Fortuny, Muslim-style lamp, circa 1870-1872

Right from his first journey to Morocco, where he went for the purpose of undertaking the commission given to him by the Diputació of Barcelona (provincial government), to depict the epic exploits of the Catalan volunteers who, from 1859, served in the Spanish army fighting in the African War, the artist began to demonstrate a liking for this kind of work. In some of his works from that period we find the echo of the motivation that contact with North African culture awoke in him, more pronounced in the case of the drawings.

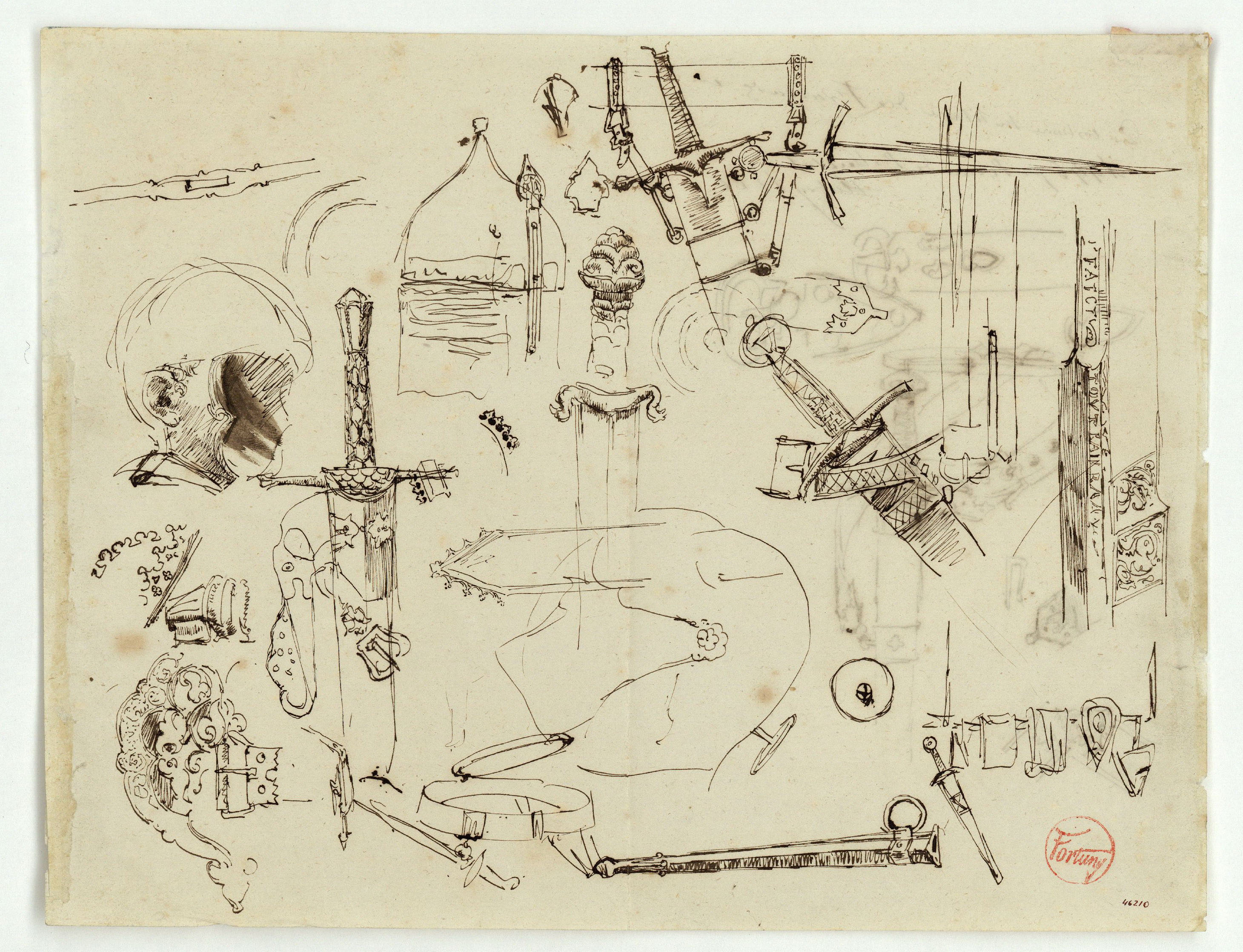

From this period there are rough drafts, sketches, as well as more finished compositions, made to depict objects classed as orientalist: muskets, lamps, carpets, utensils for everyday use and other types of small weapons, daggers for example.

Marià Fortuny, Swords, helmets and other objects, circa 1867-1872

The most significant thing, in my opinion, was the fact that all these material objects, besides fulfilling a desire to accumulate, also brought about a change in the direction his artistic creativity took. And it is here where we begin to discover the close connection established between his painterly temperament and his growing taste for collecting. I am referring to the wish the painter was to reflect in his work to outline an intellectual framework, which could help to make the historical scenes more credible.

The unfinished Battle of Tetouan constitutes a first touchstone for incorporating elements of narrative support that shape his need to adapt more thoroughly to the principle of verisimilitude. In spite of its evident failings, beginning with the inability demonstrated by the painter to comply satisfactorily with the conventions of history painting (maintaining certain precepts such as the epic and heroic significance of the actions, and respecting the exemplary and didactic nature of the account, among others), this monumental painting prefigures a set of ideas, a worldview, that evinces a profound knowledge of the historical sources.

Marià Fortuny, The Battle of Tetouan, Rome 1863-1865

All these principles crystallized in a highly emblematic work, The Print Collector. In its three versions he displayed a range of scholarly knowledge that enabled him to include many of the objects that were already part of his large and rich antiques collection.

Marià Fortuny, The Print Collector, Rome, 1866

As time passed Fortuny’s fame as a reputed specialist grew. In the opinion of his friend, the landscape painter Martín Rico, he was an expert whose sixth sense enabled him to distinguish between authentic and fake objects, and to recognize the value of the pieces that passed through his hands. In this respect, his time in Granada, from 1870 to 1872, consolidated his fame.

Among his outstanding achievements we find the Fortuny Tile (Instituto Valencia de Don Juan) or the Fortuny Vase (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg), a Hispano-Arab vase sold for a high price at the Atelier Fortuny auction held in the Hotel Drouot in Paris in 1875.

Marià Fortuny, The Studio of Marià Fortuny in Rome, Rome, 1874

The majority of the pieces auctioned can be seen in the photographs of his atelier in Rome. This studio also became a museum that helped to confirm its owner’s merit and to spread a highly iconic image. This type of large Atelier, indebted to French models, also helped to construct a series of myths around a figure whose untimely death, at the age of 36, set the course for nineteenth-century Spanish painting. Behind him he left a distinguished group of followers, many of whom, through the excessive use of repetitive and stereotyped formulas, contributed to blurring the original talent of the finest Spanish artist of the nineteenth century, after Goya.

Related links

‘The Battle of Tetouan’ of Fortuny. From the Trench to the Museum

Fortuny (1838-1874) Vídeo, 6:16

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats