Joan Yeguas

In the current exhibition Maternasis, curated by Àlex Mitrani, and which can be visited at the Museu Nacional until 25 September 2022, you can see a Virgin of Good Hope. The work has been chosen as a symbolic and explicit representation of the gestation of the Virgin’s pregnancy, a subject little known by the general public and which highlights the biological act of being a mother (in this case it is also a divine act, as she is to become the mother of God). The painting is in tempera on wood and its dimensions are 120 x 76.5 cm. It is dated to the first quarter of the 16th century, and is usually kept in the storage rooms. As to the authorship, different historians such as Leandro de Saralegui (1932), Elías Tormo (1933) and Chandler R. Post (1935) have pointed to an anonymous artist situated in the circle of Roderic d’Osona (Valencia, circa 1440-1518), considered to be one of the representatives of Valencian painting at the beginning of the Renaissance period.

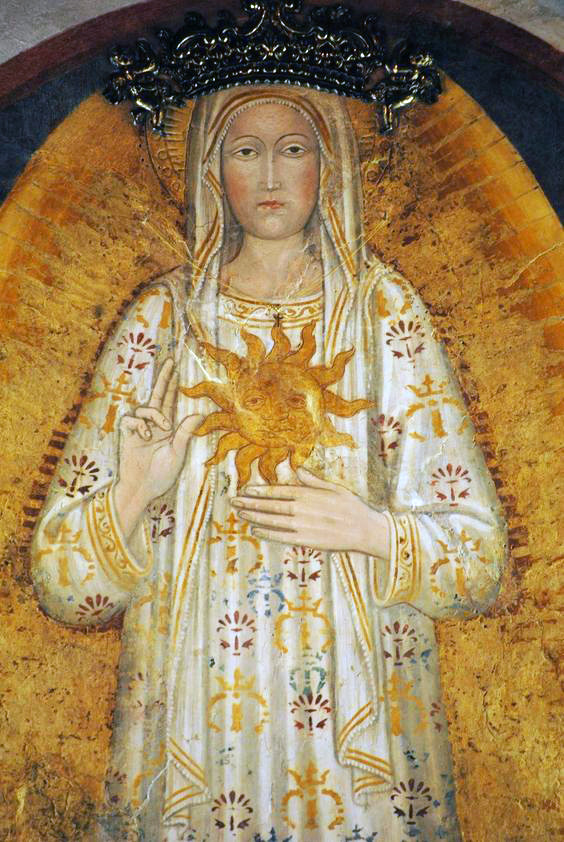

Circle of Roderic d’Osona, Our Lady of Good Hope, first quarter of the 16th century ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The work was purchased in 1923 from the brothers Sebastià and Carles Junyer Vidal, the former a painter and the latter an art critic, and both of them collectors. Their reputation has been tarnished over the years, given that their workshop faked some paintings (Gothic ones especially), carrying out abusive restorations with a wish to deceive. The purchase of this work was agreed at a meeting of the Board of Museums of Catalonia held on 15 June 1923, at which it was proposed “to purchase from the Junyer brothers a panel by the Valencian school, from the early 16th century, depicting the Doubt of Saint Joseph, and for which they are asking 3,500 pesetas, for 3,000”. Despite the delicate condition of the painted surface, and after several tests (infrared reflectography, X-rays and Ultraviolet photography), it has been possible to observe isolated retouches due to slight losses of polychromy – one of the areas is the Virgin’s left eye as the spectator looks at it – and other interesting aspects, related to the artistic creation and the underlying drawing, which will be analysed at some time in the near future.

Ultraviolet photo of the panel of Our Lady of Good Hope by the circle of Roderic d’Osona ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The composition depicts the figure of the Virgin seated on a cushion, with her hands raised in an act of prayer and admiring contemplation. Mary’s womb is slightly swollen, suggesting that she is pregnant, a fact that is certified with the image of the naked Child standing, holding the orb and wrapped in sunbeams. The Virgin is wearing a crimson tunic and a golden cloak decorated with a floral pattern, and she is behind a lectern with an open book on it. In the background, Saint Joseph appears asleep, with his eyes closed and reclining, resting his head on his left hand. This detail refers to The Dream of Saint Joseph, a test of faith to which Mary’s husband was subjected, in which an angel appears to him in dreams and reveals to him that she had been made pregnant by the Holy Spirit (Matthew 1:19-24), something that generated doubts in him. The scene is often also called The Doubt of Saint Joseph, and here I link up with the name the work was given when it was purchased in 1923. Finally, in the top right-hand corner, an angel holds a phylactery without any writing on it, while in the top left-hand corner there are some curtains. The action takes place inside a dwelling, where we see the tiled floor, whose lines are projected into space in an attempt to give the feeling of geometric perspective.

The infant gestating inside the Virgin’s womb, detail of the panel Our Lady of Good Hope ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The Virgin appears pregnant in some episodes that are echoed in works of art. One is the narrative and group painting The Visitation, in which we find her next to her cousin Elizabeth, also pregnant with Saint John the Baptist. The other one is a devout image of the Virgin, beyond her role as a protective figure of Jesus, in which her maternity is highlighted. This version is named the Virgin (or Our Lady) of Good Hope or of the Expectation, because she is expecting the Nativity of the Son of God (in a Catholic context, there is a record of festivities celebrating the maternity of Mary since the 6th century AD, but it was not established dogmatically until the Council of Toledo in 656). In some places, Our Lady of Good Hope is also called Our Lady of the “O”, due to the ovoid shape of her womb. In Italy there is Our Lady of Childbirth, and also of Desires.

Pere Mates, Visitation, 1536, currently on long-term loan to the Museu d’Art de Girona ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya /Gregorio Fernández, The Immaculate Conception, central figure in the altarpiece of the Immaculate Conception in Astorga Cathedral, 1627-1630.

The depiction of the pregnant Virgin has its origins in the woman in Revelation (Revelation, 12:1-5): “And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars: And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered. […] And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron”. A woman dressed as the sun, that is, who gives off divine light with sunbeams. It is a prefiguration of the birth of Christ, the son of the woman in Revelation. In this case, however, what catches the spectator’s eye is the Child gestating inside the Mother’s womb, a sort of resplendent full colour ultrasound scan of the holy embryo. The fact is that the Virgin is fertilized and allows the fruit of her womb to be seen, and Jesus appears with a halo as if he were the personification of a radiant sun.

Andrea di Bartolo di Jesi, Our Lady of the Sun, 1471, Belvedere Ostrense

The relationship between light and divinity (or truth) is a term much-used throughout history, and, on the contrary, its opposite (darkness or shadows) is the sign of evil and bad things. The iconographical explanation should be interpreted as an allegory of the light that has to illuminate the world, often based on a prophecy by Malachi (Ml. 4:2): “unto you that fear my name shall the Sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings”. A text that should be interpreted as the second coming of the Lord, in which he will impart justice, the reason why he is often called the Sun of Justice, protecting and illuminating all the good people.

Anonymous, Our Lady of the Sun, early 16th century, Mosque of Cordoba / Master of the Dresden Prayer Book, Our Lady of Good Hope, circa 1486, Monastery of El Escorial (Manuel Trens, La Virgen en el arte español, 1952).

Manuel Trens, in his great monograph on the iconography of the Virgin (1952), states that this model first appears at the end of the 15th century; to be precise he mentions a miniature in a “Book of Hours” painted in 1486 and kept at El Escorial (with illustrations attributed to Gerard David and the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book). But before this date there is already a record of the altar of Our Lady of the Sun in the Mosque in Cordoba (although the painting is from the early 16th century), in which we find a resplendent Christ, and Mary with her hands raised as well. Another Virgin that can be related to this is a Virgin of the Sun holding the sun in her arms, painted by Andrea di Bartolo di Jesi in 1471 and located in the town of Belvedere Ostrense (Ancona).

Francisco Rizi, Our Lady of the Expectation Appearing to Simón de Rojas, circa 1650, British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum / Anonymous, Our Lady of the Expectation, second half of the 17th century, Archbishop’s Palace, Lima

This iconographical resource was considered indecent after the Council of Trent (1545-1563), and it disappeared in most of Europe. However, it was revived in Madrid at the beginning of the 17th century, thanks to the actions of the Trinitarian Simón de Rojas at court, who promoted the cult of Our Lady of the Expectation, due to a supernatural vision that he had had when he gazed upon the pregnant Virgin, with the figure of the Child Jesus blessing the world inside her; an episode reflected in a drawing by Francisco Rizi conserved in the British Museum in London. Rojas ordered an image from the sculptor Juan de Porres, now lost but known through some paintings and prints, like one that is conserved in the Archbishop’s Palace in Lima (Peru), with poetic quotes by Fra Luis de León, something that helped to spread the iconography in Hispanic America.

Devotion to the light has to be associated with ancient sun worship, based on the natural cycle of the seasons. The Roman deity of Sol Invictus was a sun that defeated darkness after the winter solstice, the reason why it was celebrated after 21 December, when the days began to lengthen. Curiously, the Son of God was also born after the solstice; the word Nativity comes from the Latin nativitas, meaning birth, applied first to the birth of the light and then to the Nativity of Christ.

Sol Invictus, altar dedicated to the god Malakbel in Palmyra, 2nd century AD, Capitoline Museums, Rome / Antonio Sarti, badge of the Company of Jesus, detail of the high altar, 1841-1843, church of the Gesù, Rome

The iconography of a Christ Child wrapped in sunbeams was simplified to the mere depiction of the Sun, as in the painting by Joan de Sarinyena from the Carthusian Monastery of Santa Maria Porta Coeli in Valencia, dated to about 1603 and now conserved in that city’s Museum of Fine Art. With the same background, the iconographical derivations can be infinite, like the badge of the Company of Jesus (the Jesuits), which reproduces a radiant sun and inside it the initials IHS (the monogram of Jesus’ name).

Joan de Sarinyena, Our Lady of the Expectation with Angel Musicians, circa 1603, Museu de Belles Arts de València