Mireia Mestre

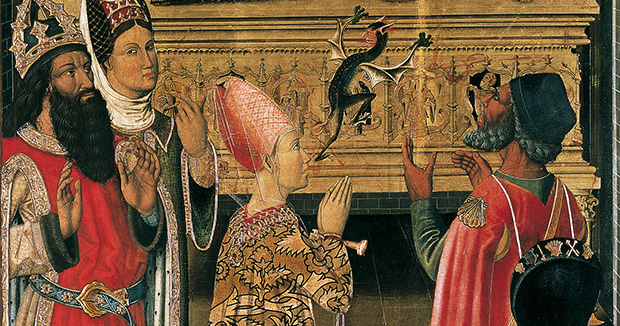

Detail of Princess Eudoxia before the Tomb of Saint Stephen, Vergós Group, 1495-1500

The properties of gold, the bright yellow colour, the ductility and the fact of it being immutable, have been ideal, not just for minting coinage, but also for its use in the arts of every civilization. It has always been a rare, precious, material, reserved for worship, associated with eternity and divine power, but also with ostentation and wealth.

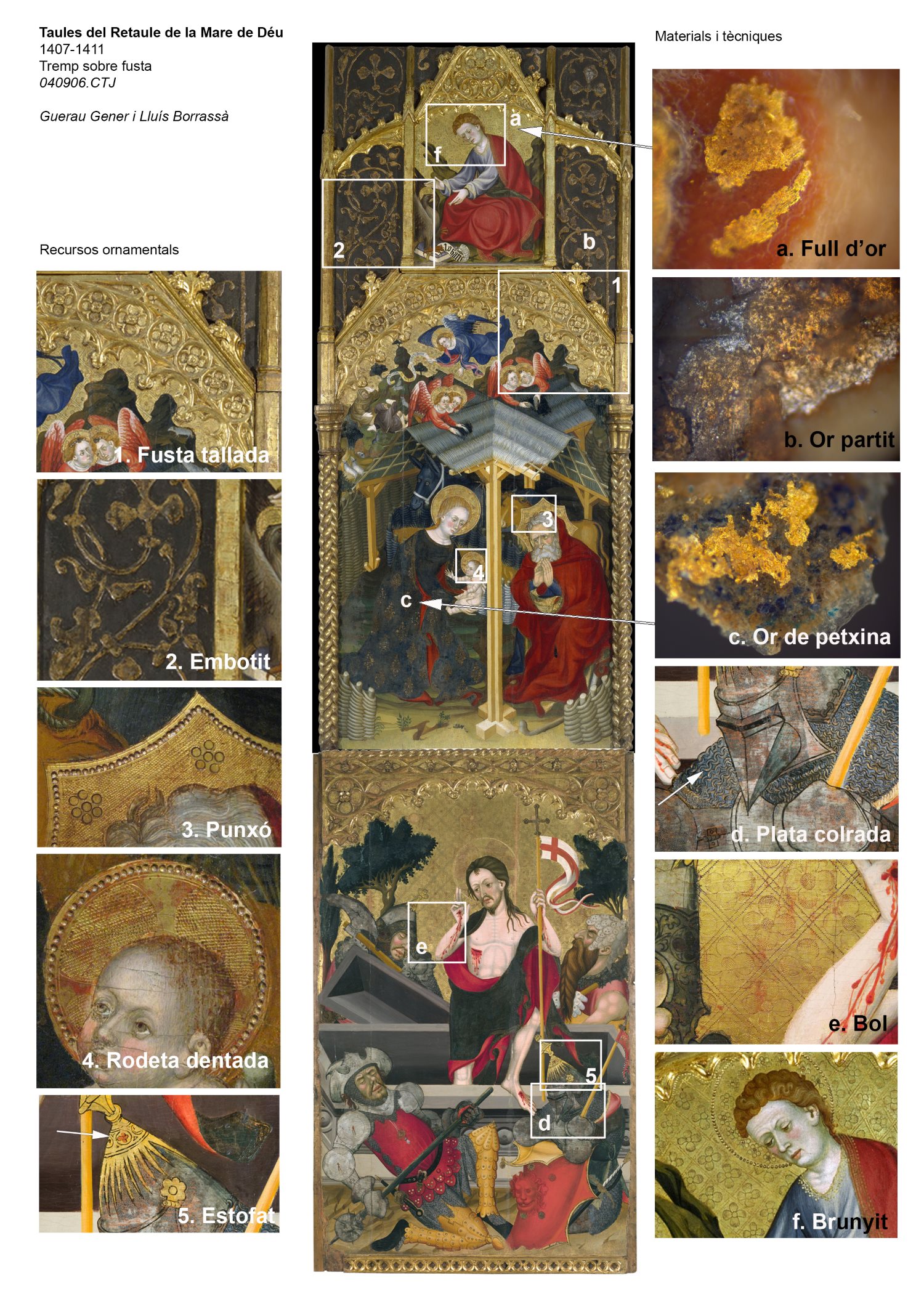

In painting, gold, and other metals too like silver and tin, are used in the form of very thin sheets that are stuck to the surface of the support, suitably prepared. Strolling through the museum’s medieval art rooms, and especially through the Gothic art collection, our attention is drawn especially to the constant presence of gold backgrounds on altarpieces. If we look more closely, we realize that the backgrounds, apparently of smooth gold, are finely worked with incised drawings, decorations painted with transparent coloured lacquers onto the sheets of metal, small repetitive ornamentation engraved in the gold (punching) and even decorations in relief, also gilded (inlay).

The haloes, crowns and mitres of many of the figures depicted in the compartments of the altarpieces are also gilded and direct our gaze towards the splendour that surrounds them. The most elegant and precious clothes have gilt ornamentation, sometimes applied over a layer of colour, at other times achieved by painting decorations of an opaque or transparent colour over the gold, or by scratching the superimposed paint to allow the gold underneath to show through. All this is to imitate the embroidered motifs and the fabrics with coiled silk threads of very thin sheets of gold and silver (estofat [quilting]), so highly prized in the period.

Types of sheet metals and the specifications of the contracts

In the Middle Ages, artists worked mostly by specific commission and the clients decided what materials they had to use. In general, painters purchased the most expensive materials that the commission they had been given and the contract they had signed would allow for, but they did not accumulate them due to the lack of sufficient spending power. Investment in this material when painting an altarpiece was usually considerable and the sheets of metal generally represented a substantial part of the total cost, as did the cost of the blue pigments such as azurite and, above all, lapis lazuli.

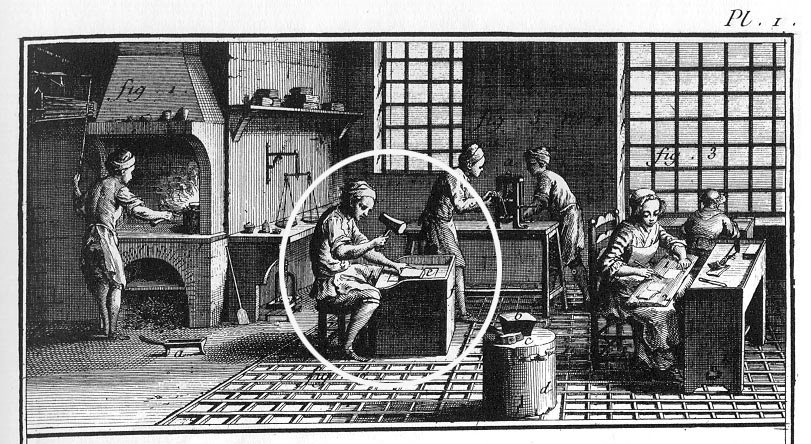

They were purchased from spice merchants or apothecaries. It was these shopkeepers who sold local or imported products, like for example drugs, spices and pigments of animal, vegetable and mineral origin. These retailers supplied the metal sheets, but they were made by specialist craftsmen, goldbeaters, beating the already flat metal with a hammer to obtain thin laminas, placed in between parchment, which they eventually turned into sheets.

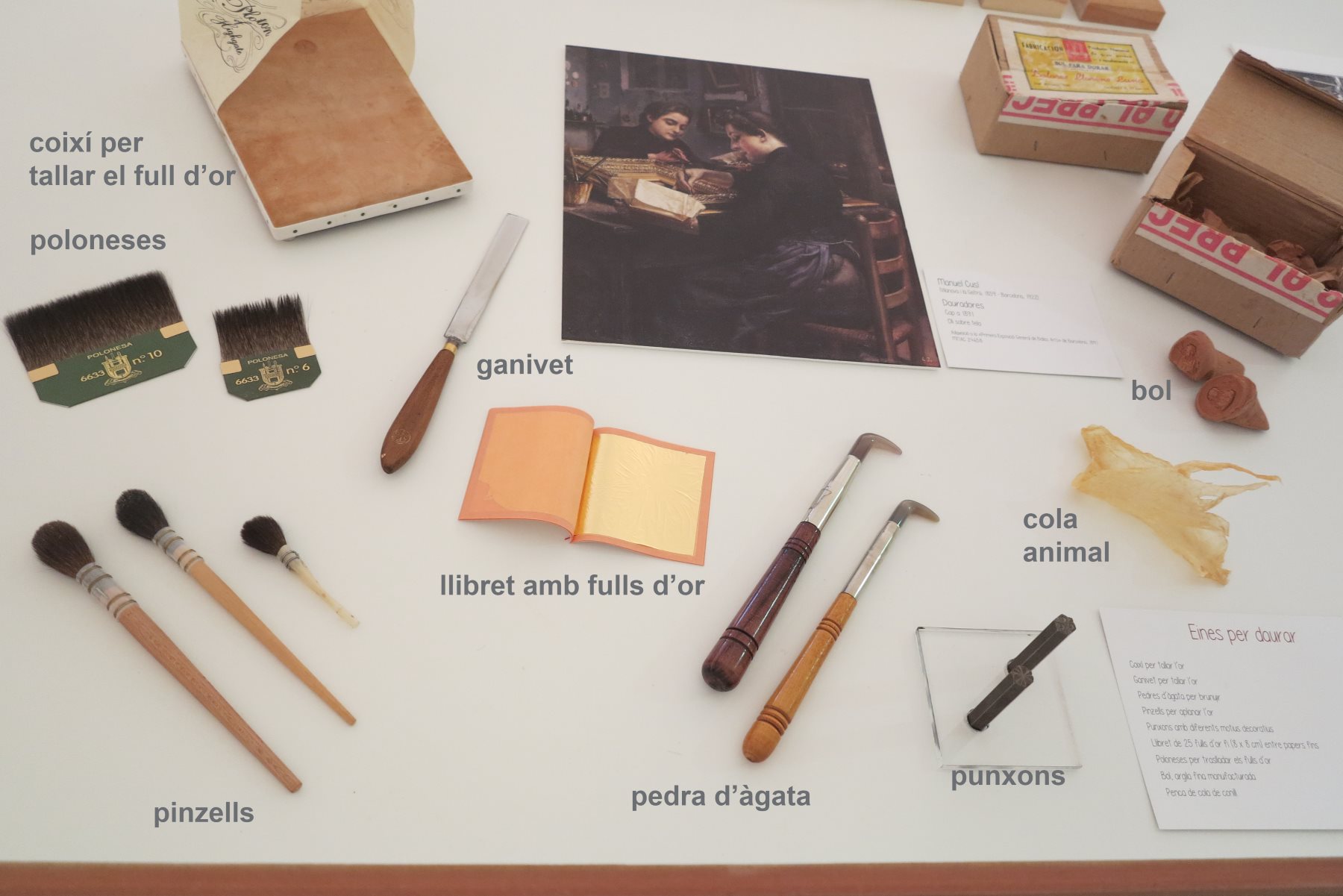

To obtain the effect of gold in painting on wood, painters used metal sheets of varying quality:

- Gold leaf was the most common. To ensure the quality of the gold, Catalan contracts often specified that it should come from Florentine florins, medieval coins of 24-carat gold – pure gold in other words – used quite widely in Western European countries. The gold leaf could be thicker and heavier, and then it was twice as expensive as the gold leaf most commonly used because it was more hardwearing and less vulnerable to surface wear and tear.

- Zwischgold consisted of a very thin sheet of gold beaten onto a sheet of silver, to which it was welded. It was a material that cost half the price of gold leaf because it contained less gold, it tended to turn black over time and it had to be varnished to avoid corrosion. The sheets were larger than those of gold leaf and somewhat paler in colour.

- Sheet silver could be varnished with yellow-tinted varnish, mecca gilded o corladura, to obtain a golden appearance at a more affordable price. It was applied especially in unimportant parts of the altarpiece. Sheet silver could be used without yellowing for soldiers’ armour, swords or silver-plated items of precious metalwork.

Print representing a goldbeater’s workshop. Source: Encyclopédie Diderot d’Alembert, 1784 (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Procedures for applying gilt

Some painters had an assistant specializing in gilding. When the wooden structure was ready, with several layers of preparation of plaster and glue, and the painter had drawn the composition on it that he wanted to depict, incisions were usually made that clearly marked out the areas that had to be gilded such as the backgrounds, the clothes or the haloes. Sometimes, the preparatory drawing was covered with a very thin layer of preparation, almost transparent, to avoid it showing through and being visible in the top layer of paint.

Materials, techniques and decorative resources for gilding (click the image to enlarge). Graphic: Paz Marquès Photos: Marta Mérida

When it was wished to add decorative motifs in relief (embotits), for example beads or floral elements, the plaster and the liquid glue was dripped from the paintbrush, and when this stucco applied on the preparation was dry, it was modelled with scraping irons, following a pattern. On other occasions decorations were stuck to it, previously obtained using moulds (a pastiglia), made with this same material.

Detail of the rotella of Nativity, Guerau Gener, 1407-1411. Photo: Marta Mérida

From this moment onwards, they could begin to apply the layers of Armenian bole, the thin yellowish or reddish clay that was mixed with a distemper of rabbit-skin glue in the areas that were to be gilded. The top layer could be polished to make it more impermeable. To stick the metal sheets to this cushion, it was first brushed with water – which regenerated the animal glue –and the gold leaf was set in place and adapted to the surface with the aid of a flat shorthaired brush to fix it properly. Then, the metal sheets could be polished or burnished with agate stone to obtain a shiny surface, and they could be decorated by pressing in small designs with the aid of punches and rotellas, following patterns.

When the metal sheets were painted with an opaque colour, wood or ivory tools with a blunt tip could be used to gently scratch the paint and reveal the gold, creating a gilt-polychrome pattern. To achieve effects of transparency on the gold, transparent coloured lacquers were applied with a paintbrush. This technique was not used to gild decorations on the paint layer; it was gilded with shell gold, crushed gold leaf, which was stuck on using some kind of agglutinant and applied with a brush.

For mural painting, however, treatise writers recommended sheets of tin that had to be thicker than those of gold or silver, as tin is more difficult to flatten. Whereas gold leaf was between 0.2 and 5 microns thick, a sheet of tin was between 6 and 8.5 microns. As it was thicker, tin could create relief on top of the plastered wall or other supports. Sheets of tin seem to have been sold with a gilt appearance, coloured with yellow, green or white colradura.

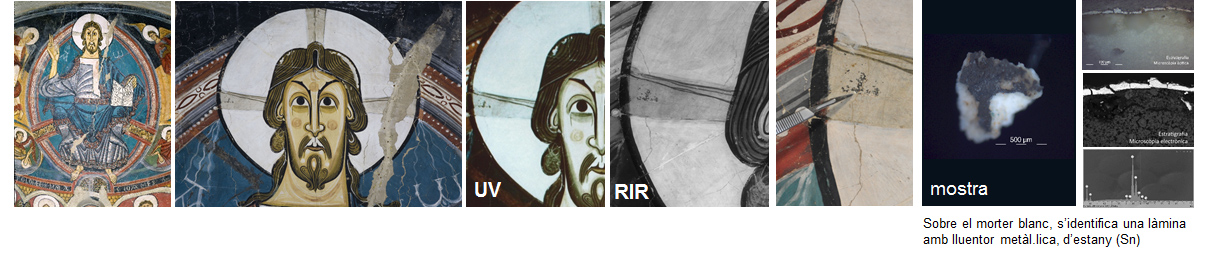

As a precedent, in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya’s Romanesque mural painting, traces of sheet tin have been found in the cruciferous halo of the Christ of Sant Climent de Taüll.

Apse of Sant Climent de Taüll, circa 1123. (Click the image to enlarge)

Example of an extract from a treatise: “Having now taught you how to paint in fresco, in secco, and in oil, I will tell you how to embellish walls with gilded tin, white tin, and fine gold. And take special care to use as little silver as possible, because it does not last, and becomes black on walls and on wood, but loses its colour quickest on walls. Use instead of it beaten tin, or sheets of tin. Beware also of alloyed gold (pro di meta) which quickly turns black.” (Cennino Cennini, Il libro dell’arte, 1390 Chapter XCV.)

With the project Exploring Gold, on display until 18 June, we have wished to show how artists used gold, and how the museum’s conservators-restorers have followed different criteria for working on gilt throughout our history. The project will remain available on the website.

Conservació preventiva i restauració