Núria Prat i Pere de Llobet

What lies beneath the visible polychromy?

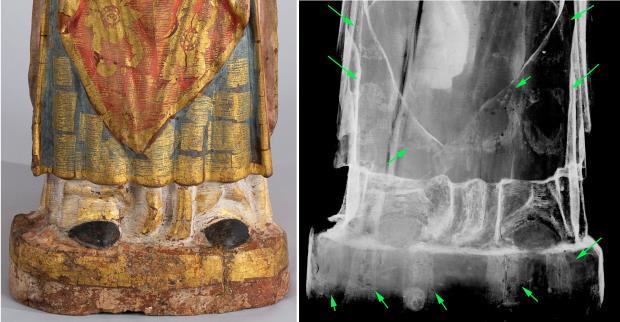

The carving is of Saint Nicholas of Bari, dressed in bishop’s robes, with mitre and chasuble. With his right hand he is blessing and in the other hand, now lost, he was most probably holding the crozier. The carving is Gothic, while the polychromy we can see is later; it appears to be Baroque, with floral decorations and sgraffiti on gold. The original polychromy might well have been damaged, because it was completely re-polychromed and we do not know why. The whole sculpture was re-plastered – over the Gothic polychromy – and polychromed as we see it today. Through close observation of the gaps on the bottom of the carving, it can be deduced that there is another layer of polychromy underneath, as the X-ray image confirms for us.

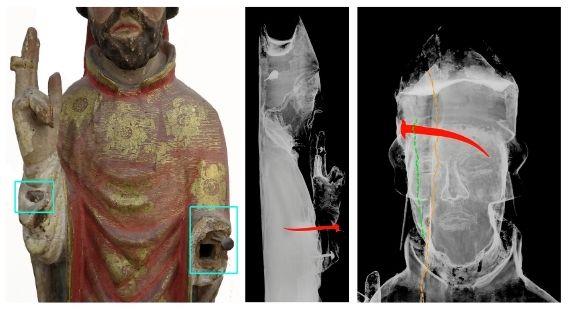

The forged nails in the carving

The main body of the carving is one single solid block of wood, and the arms were separate pieces attached to it. X-rays reveal to us that the carving has five forged nails, two of which served to attach the hands to the trunk.

The other forged nails inside the carving. What is their purpose? Were they repairs? The third nail is in the head. Could it be the result of some previous work? We think so, that it was done when the work was made, to stabilize a crack in the support.

Two more forged nails can be found in the right hand, in the middle and index fingers. As in the previous case, we think this could have been done when the piece was first conceived.

The interpretation made upon seeing these forged nails inside the carving, is that a block of wood was chosen that was cracked to begin with. The carving work was done and the forged nails were inserted to strengthen the support. Then the carving was plastered, polychromed and gilded. The use of cloth has not been detected.

The carving of Saint Nicholas presents a crack that runs vertically from the head to the base.

The back of the carving is flat and was not polychromed or hollowed out; therefore, the most usual thing in this kind of work would be to see the bare wood, but this is not the case, while it is for the carving Deacon Saint, which has also been loaned for the same exhibition, North & South, but only in Vic. The entire surface of the back of the carving of Saint Nicholas was covered with granular mortar (composed of a glue/adhesive and an inert load with a considerable particle size), which notably increases its weight. The carving measures 98 x 24.5 x 14.8 cm and weighs 9.1 kg. It is not known when this mortar was added, but everything suggests that it was refilled to minimize the effects of the crack in the support. Notwithstanding that, over time, the crack in this added putty has got longer, although the work is structurally stable

The process of cleaning the carving

The process of cleaning the polychromy and the gilt was carried out very carefully, first using various aqueous mixtures (only on the polychromy), and in the second stage using mixtures of different solvents.

The Polychrome doors or tables

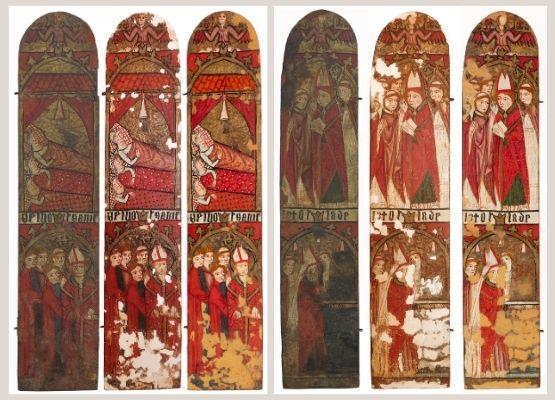

The surviving panels depict different scenes in the life of Saint Nicholas of Bari, and, unlike the carving, they still have the original Gothic paintwork, but with large gaps and repaints.

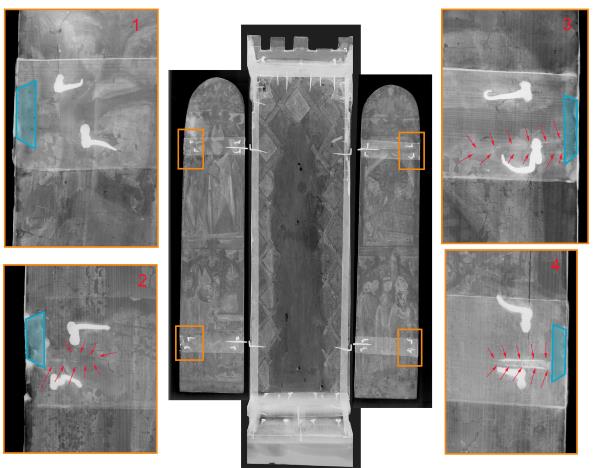

Did the tabernacle-altarpiece have double doors or panels?

This was the question we were asked by the museum’s Medieval Department. Now, only the two side panels are conserved and it did not look like there was any continuity. We had to find some signs on the edges of the doors to show us that the system of fastening the front wings, which closed the tabernacle, went there.

The X-ray study was crucial! In a previous intervention (not documented), some grafts or pieces of wood were placed in the edges of the panels, coinciding with the crosspieces, and in this way, all trace of the points where the front doors were fastened was hidden. The X-ray shows that, apart from the grafts, inside the panels, some gaps in the wooden support appear, and inside, the remains of the iron can be seen. It is showing us that, in the past, there were some iron elements, that is, the fittings holding the hinges in place. It was these that made it possible to open and close the lost doors

The restoration of the doors: before and after

The polychromy and the gilt on the doors were covered by a dirty, brownish layer of resin. Large areas of the painted scenes and the gilded backgrounds had been lost. In a previous intervention (not documented), these gaps were rather carelessly stuccoed and repaired. For example, putty was applied, in some places leaving a rough surface that covered more than the gap, and the original paintwork, which over the years had darkened, was painted over. In the process of restoration these repaints have been eliminated and the stucco that was not conserved in a good condition has been adapted or removed

It was decided, to begin with, to fill the largest areas of lost colour with a plain neutral dye. A trial was carried out and it was observed that the neutral colours became too important and interfered with the appreciation of the work. Eventually, therefore, some vibrant neutrals were made using different shades and were superimposed using glazes and dots. The repaint was done with powdered pigments agglutinated with retouching varnish.

Temporary exhibitions often make it possible to rescue works from ostracism, as is the case here with this Tabernacle-altarpiece of Saint Nicholas.

The X-rays were taken by the museum’s X-ray team (A.Comella, A. Masalles and V. Martí).

Related Links

From the storeroom to the display cabinet: the recovery of the Altarpiece-tabernacle of Saint Nicholas /1

North & South. Mediaeval Art of Norway and Catalonia 1100-1350

Medievalia. Revista de Estudios Medievales, Vol. 23, Núm.1

“Una torre per a un bisbe universal”, Favà, Cèsar. North & South : medieval art from Norway and Catalonia 1100-1350 / editors: Justin Kroesen, Micha Leeflang, Marc Sureda i Jubany. [2019] [exhibition catalog, p. 123-125, cat. núm. 14 fig. P.123. ].

Pere de Llobet

and

Restauració i Conservació Preventiva