Francesc Quílez

Only on very few occasions during his career as an artist did Fortuny develop the theme of the female nude. It is a genre towards which his attitude was always preventive and for which he felt no special predilection, except for two highly iconic productions that over time have become two of his most admired works.

The Odalisque: Fortuny’s first foray into the female nude

The first of them, The Odalisque, a work framed within his already well-known liking for orientalism, was made in Rome in 1861, and although it is an image that still arouses great critical unanimity and great admiration, it should not be forgotten that it met the artist’s formative needs. After all, the painting came into being as a reflex action, a compulsory response to the Diputación de Barcelona’s request for an example of the progress he was making as an artist, something to provide confirmation that the decision it had made, to award him a grant for his stay in Rome, had been worth it. Prior to that, in 1860, the Reus-born artist had made his first journey to Morocco and had begun working on, among others, the painting of The Battle of Tetouan.

It is important to bear this historical context in mind because, contrary to what one might expect, the painter’s approach to orientalism was to some extent disappointing. Far from avoiding cultural clichés and stereotypes, or approaching the subject without prejudice or literary indebtedness, his attitude was to blatantly emphasize the most conventional image, renouncing the cultural baggage that he had assimilated during this first stay in Morocco and which had very beneficial repercussions for his development as a painter.

Carmen Bastián, a disconcerting and enigmatic work

Ten years later, in the context of his work during his stay in Granada, Fortuny once again approached the theme of the female nude, and in the time that had passed the metamorphosis was complete. Literary references and the evocation of mythological or sacred types had been abandoned, and they had made way for an original work, disconcerting and at the same time complex because of its enigmatic nature. It is a puzzle that we still find hard to figure out; it poses a large number of questions for us, and also questions many of our own certainties about the painter, or about the way he approached a subject that was taboo in his day.

Carmen Bastián, due to its rarity and its exceptional nature, is undoubtedly an unclassifiable work. Is it a portrait, a costumbrista genre painting, or is it a provocation, a sort of extravagant divertimento?

To begin with, there can be no doubt that it is a painting that must be interpreted from the perspective of privacy, intimacy even, I would dare say, because it falls within the category of private artistic practices, intended only for the painter’s solace and entertainment. However, by becoming part of a public art collection, its permanent exhibition has put paid to the initial intention to keep it hidden, for the painter’s eyes only. This leaves the artist’s original idea in doubt, in suspense, and causes a problem of aesthetic reception, since it was never Fortuny’s intention for it to be purchased by a hypothetical customer, and I am sure he never imagined that this irreverent painting would one day hang on the wall of a room in a public museum.

The proof is that the family, unable to accept a work of these characteristics, as they considered it to be an aberration, turned it into a prohibited rarity, an object that it was necessary to hide from view because it evoked the ghosts of the past and even contributed to demythologizing the aura of respectability that had always accompanied him, his reputation as an honoured artist. It was necessary to exorcize this sinful “deviation”, by veiling the composition, hindering its contemplation, since it generated great embarrassment and was not easy to explain. Far from noticing its magnetic power, celebrating it as a real pictorial achievement, the family took a conservative view and decided not to share it, subjecting it to a moral judgment that condemned it eternally to the most absolute ostracism.

This appraisal would explain the existence of a legendary tale that was told, which helped to shroud it in mystery; it mentioned the existence of a curtain that prevented it from being seen, and it was only possible to gain access to it after drawing back this curtain. In some ways, the family’s behaviour with the covered image showed certain similarities with the famous private cabinets of kings, whose purpose was to hide prohibited images of naked women, which were uncovered on special occasions. In this case however, for this behaviour there was a sacred or mythological pretext that allowed the mystery to be unveiled and shared with, as you might expect, a male elite.

The vulgarity of Carmen Bastián in the midst of a moralistic and class-based society

Although it no longer scandalizes us, we must admit that it is a disconcerting work, extraordinary almost, difficult to read and interpret, and it cannot be denied that, apart from certain stylistic aspects, it is hard to recognize in it the characteristics that define its creator. The fact is that the supposed eroticism of the image is toned down and even neutralized by the vulgarity and the impertinence with which the sitter displays her sex, with no qualms at all, no sensuality. Nor is it a misogynistic, voyeuristic or lascivious exercise, since the woman, with her uncouth pose, is not contemplated as an erotic or sensual object that might be capable of arousing men’s erotic urges.

Far from objectifying the image, or establishing codes shared and recognized by the viewer, Fortuny apparently allows himself to be intoxicated by the banality of the image, offering no moral judgment of the sitter’s behaviour. Nevertheless, in the representation there does seem to an underlying desire to highlight the unprejudiced pose of a woman who does not allow herself to be influenced by either customs or conventions, or by the moral values of bourgeois society. In this respect, the painter merely shows, with a rather classist attitude –paternalistic and condescending even – the image of a woman who is guided by principles that could be described as primitive, and who responds to impulses and instincts that have not been subjugated or corrected by bourgeois manners and morality.

In some ways, without intending to, the artist adopts an attitude of moral superiority, since he congratulates himself for being able to gaze upon and show this free, disinhibited pose. At the same time, however, he does not hide the need to make it quite clear that he belongs to another social group; a group in which this kind of action, considered vulgar and coarse, has no place because it is untimely and irrational.

These class prejudices could also be extended to the painter’s social circle. In all his closest friends, a work of this kind would have produced a logical reaction of incomprehension and dismay. We will surely agree that if we could travel back in time and we had the opportunity to view it, our reaction would more than likely be negative.

A provocative work, without meaning to be

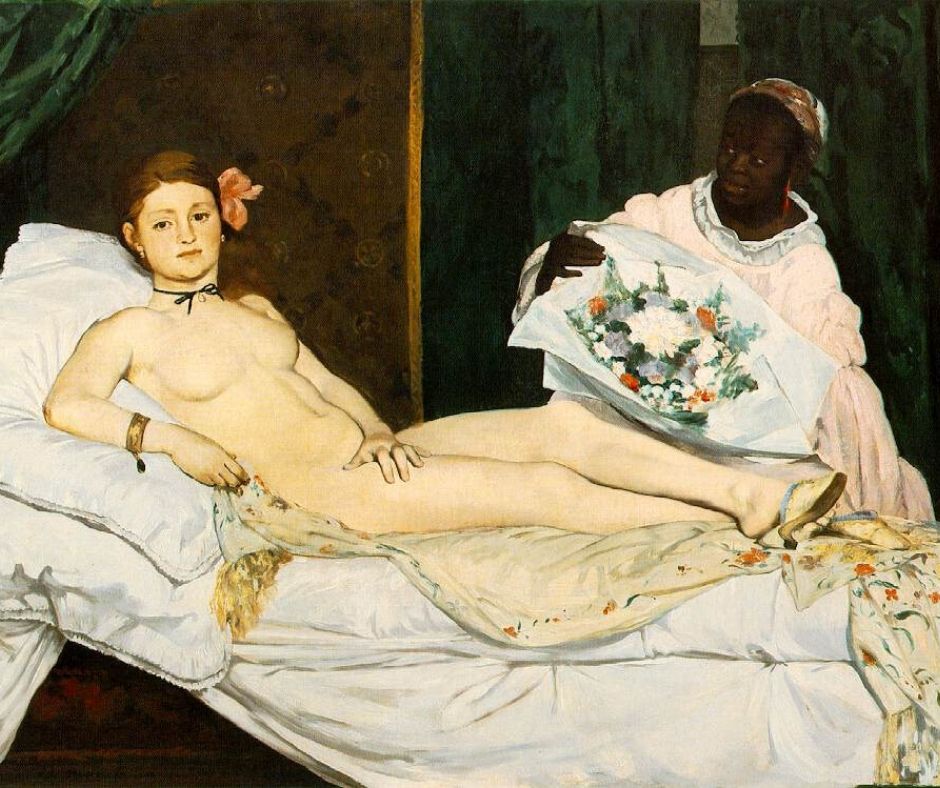

In my opinion, the above reflections would therefore cast doubt on the composition’s supposed transgressive intent, since the painting was under no circumstances designed to satisfy a desire to provoke, nor can it be framed in the context in which other contemporary works of a similar nature emerged, for example Manet’s Olympia, or The Origin of the World by Courbet, to which it has very often been compared. I believe that the similarities are exaggerated and gratuitous, because in the case of these two works, the artists deliberately set out to challenge particular social and cultural conventions, to which we should add, questioning the traditional role assigned to artistic genres, among other aspects.

However, despite what has been said, it is also no less true that observing the painting leaves no one indifferent, and it often makes a great emotional impact and even produces a logical reaction of astonishment. This is because, as I mentioned earlier, it is a work far removed from the painter’s sensibility, and although it may seem obvious it is an unusual, atypical product of his way of understanding the practice of painting, completely at odds with his worldview.

Carmen Bastián: An unfinished work by Fortuny

Without making any value judgments about the significance or the symbolism of such a surprising work, I would like to point out an aspect that is interesting because it enables us to connect with a leitmotiv very much present in all his work: that of the non finito. It is recurring feature that opens up a different perspective and poses the need to review certain historiographical stereotypes. Not for nothing, actions of this kind cast doubt on the artist’s supposed perfectionism and preciosismo. At the same time, they speak highly of him since it is a demonstration of weakness, doubt or hesitation that leads him unexpectedly to throw in the towel, to acknowledge his limitations, his frustrations, or even – speculatively – an intention to construct an alternative option to the canon.

The actual painting, although it is a paradoxical phenomenon, belongs to the category of works unfinished, left half done, which increases its aura of mystery even more. If we look closely we can see the disturbing presence of a figure, a resource common also in other paintings by him, drawn on the white wall that encloses the composition, roughly sketched, barely outlined, and which looks like a piece of graffiti perhaps, or a simple visual doodle.

It is a silhouette that is difficult to make out, because it has been done very schematically, with a brushstroke that outlines a half-done profile and which seems to draw, or vaguely sketch, a female form.

In any case, this is yet another visual reference introduced by the artist for an unknown reason, but which ends up adopting a ludic register, a transgression conceived as an enigmatic quote designed to provoke a disconcerting reaction in the viewer. In any case, the fact that the whole composition is unfinished allows one to speculate that this figure could also have been drawn for the same reasons, and that the artist had left it half done, despite the fact that the initial idea was probably to finish it.

Related links

Marià Fortuny: painting as the representation of a worldview

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats