Lluís Alabern

Opening the museum to the community, incorporating the gaze of others, rethinking the organization of museums in several languages, generating a multiplicity of proposals at a time when there seems to be neither a predominant discourse nor model to resort to. The debate is open in many of our museums – and in this one too.

Tracing a transverse axis between public programmes, museum organization, the collection, educational links. Building bridges between so-called mass culture and “high culture” without giving rise to stereotypes or clichés. There are more questions than answers:

- what links should be established with the non-academic arts, with graffiti, documentary photography, performance and comics, among others?

- how should the story be told so that the general public perceives that a museum such as ours is a collection of unexplored stories, of iconographies with which to conquer new narratives, and that its public duty is to be an archive at the service of the citizenry?

In search of links between art produced by consensus and refugee art

The new display of Modern Art that the museum proposes in its permanent collections, in some of the temporary exhibitions, and in quite a few of the activities formulated in its programme, is attempting to begin to provide answers to these questions.

Comics are a printed cultural artefact closely linked to the mass media, and perhaps for this reason they are often kept out of the museum’s rooms. We in the institutions have yet to open our storerooms and spaces to this century-old cultural phenomenon.

Perhaps, as Ana Merino notes in her precise study of El cómic hispánico /The Hispanic Comic (Cátedra, 2003), this may be due partly to the difficulties comics have in finding their own space: “so that comics may survive being hounded by other media they first need to acknowledge their place in the cultural history of modernity”. Museums have a lot to say on this matter. It is time to catalogue, to document this recent history, to open up the museum to an idiom whose mass, popular dimension is undeniable. We have to seek the links between art approved by consensus in the circles of the official history, and the surreptitious, art that has taken refuge in the districts of popular culture.

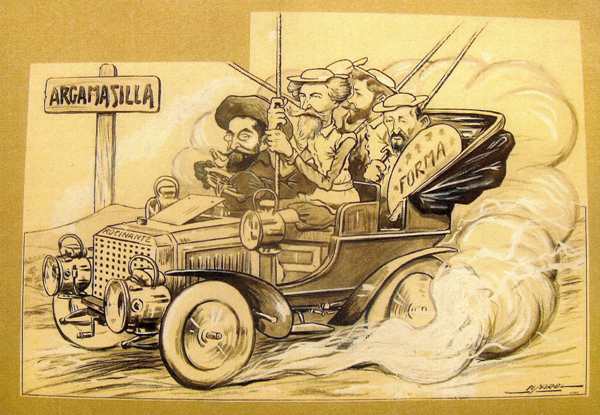

The Museu Nacional’s collection of drawings, prints and posters

Our museum has a large collection of drawings, prints and posters that includes originals by almost all the draughtsmen of the turn of the last century – often displayed in the presentations of the permanent collection and in different temporary exhibitions – and the principal publications that witnessed the birth of what we might call an artistic precursor of what we now know as the comic. To a large extent the satirical press of the 19th century advocated the world of comics. It is something, however, that museums seem to have forgotten, and which remains virtually unknown to the young readers of comic books and graphic novels. Experts such as Josep M. Cadena or institutions like the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc have for years been presenting the connections between drawing, the popular arts and high art. However, nobody has yet decided to conduct a deep analysis to establish the criteria and spaces that correspond to comics, and their relationship with the rest of the arts.

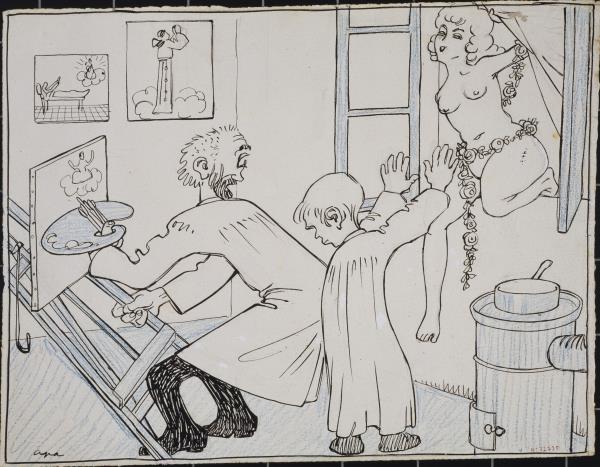

In our cultural environment a connecting thread can be drawn that begins with draughtsmen such as Manuel Moliné, Josep Lluís Pellicer, Josep Costa Picarol; magazines such as ¡Cu-Cut!, L’Esquella de la Torratxa, La Campana de Gràcia, Gil Blas, La Tomasa, Papitu, etc.; it includes masters of the popular graphic arts such as Apel·les Mestres, Joan G. Junceda, Ramon Casas, Xavier Gosé, Feliu Elias Apa or the great Ricard Opisso, Pere Ynglada, Lluís Bagaria, Josep Mompou, Emili Freixas, Ramon Calsina … precursors of the artists of TBO, of the post-war comics, of the collections published by Bruguera, of Cesc, Perich, El Roto, of the political publications of the Transition, underground comics, Nazario, Makoki, El Víbora.

Ramon Casas, Ciclista. L’anada (Cyclist. The outward trip) and Ciclista. La tornada (Cyclist. Return trip). First and second part of a comic strip published on l’Almanac de l’Esquella de la Torratxa (1890, p. 110 and 111). You could read a caption of the illustrations: “Al montà a la bicicleta -per emprendre un passeig llarch-, deya: Avuy de quans me vegin, l’atenció tinch de cridar” and “Y amb l’aparato fet a trossos y un gran nyanyo al mig del front tornant a burro… en efecte, -cridava molt l’atenció”.

The Comic Fair enters the Museu Nacional

It seems logical, then, that the museum should build bridges with the world of comics, and what better way to do so now than by inviting the Comic Fair and Santiago García and Javier Olivares, winners of the Premio Nacional de Cómic (in Spanish) with their magnificent graphic novel Las Meninas, to present some of their work.

In one of the spaces that the museum has decided to devote to incorporating the gaze of others, to joining forces educationally to enable us to reach the least likely type of visitor, we present a small sample entitled García/Olivares: Vignettes. We can see some sketches, discards, graphic processes, published works along with unpublished ones, by the duo formed by the scriptwriter and the artist, all of them, breaking down barriers between comics, literature and art.

We furthermore invite the writer, cultural journalist and scriptwriter Jorge Carrión to reflect on the admission of the comic to the museum. It is a first encounter between comics and the museum, but there will be more. The collaboration agreement between the Comic Fair in Barcelona and the Museu Nacional augurs continual proposals and projects.

Mediació i Programació Cultural