If there is one thing that the museums of Catalonia are noted for it is being the result, not of ancient royal collections, as is the case with the Belgian royal museums, or, closer to home, the Prado Museum, but of private collections that have been purchased, bequeathed, donated or ceded to the Museums Board or to the museums themselves. The museum has recently held a symposium with a very intriguing title: Collectors that have made museums. It is not just an intriguing title, but also a very suitable reflection if we think in terms of the museums in Catalonia.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Barcelona enjoyed great cultural wealth, accentuated thanks to the good work of the Museums Board of Catalonia (created in 1902 and with the incorporation of the Diputació de Barcelona [provincial government] in 1907) and the Association of Friends of the Museums of Catalonia (1933).

It was in this context that the role of private collectors began to stand out, patrons who, since the industrial revolution, had acquired financial power that enabled them to build up large collections. Some of them are among the names that were spoken about in the symposium: Enric Batlló, Lluís Plandiura, the politician Francesc Cambó, and artists, far removed from the corridors of power and economic circles, like Eusebi Valldeperas or Josep Pascó, who were almost certainly moved by a more erudite motive.

Whatever the case, their collections, built up over the years, whether due to a feeling of patriotism and of service to their country, an artistic ideal or a financial interest, or even due to their owner’s financial necessities, ended up, in the majority of cases, as part of Catalan museums’ collections.

The Plandiura Collection at the museum

The Museu Nacional would not be the institution it is today if it were not for the purchase by the Museums Board in 1932 of the more than 2,000 pieces in the collection of Lluís Plandiura.

Plandiura, without doubt one of the most important Catalan collectors of the twentieth century, corresponds to the definition of the typical industrialist. Throughout his life he collected thousands of art objects from all periods, creating a museum in his own home. Mireia Berenguer commented that he wished to turn his private collection into a public museum, breaking with the traditional reluctance of some art collectors and their privacy. He was proud and happy to be able to open his doors so that everyone could enjoy art, until in 1932 he sold his collection to the Museums Board.

Visual effect of one of the modern art galleries with and without the artworks of the collection Plandiura

Berenguer mentioned the great importance of this collection, not just because of its size, but for the quality of the works. “If we took all the works from the Plandiura purchase out of the museum’s rooms, the walls would be half empty.” This is because there are more than 1,300 works from this collection on the walls of the museum. As we have said, it is not just a large collection, it is also varied, and it enriched both the medieval and modern art collections, and especially the poster collection.

From the Middle Ages, there are the only “signed” frontals to be conserved in the museum: the Altar frontal from Gia and the Altar frontal from Cardet, both by Iohannes, made in a workshop in La Ribagorça, and as a curiosity a Virgin that an American lady was once determined to purchase from him.

Works so emblematic of the museum, and at the same time iconic, like Idle Hours, by Ramon Casas, or Terraced Village, by Joaquim Mir, also belonged to Lluís Plandiura’s collection.

Altar frontal from Cardet, second half of the 13th century

Joaquim Mir, Terraced Village, around 1906-1909

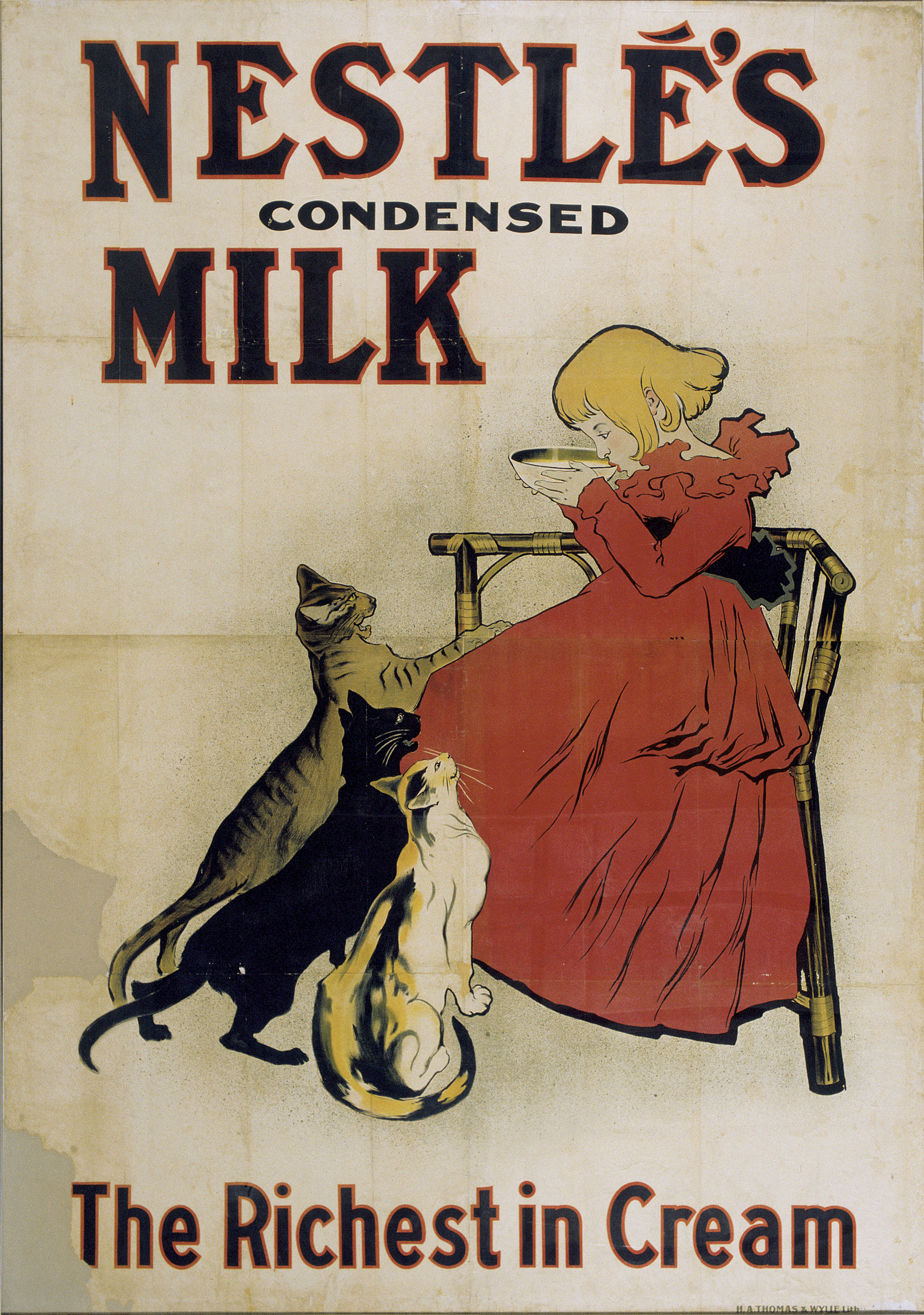

Especially worthy of mention are his posters which, together with those that entered the museum from the collection of Alexandre de Riquer, constitute the fundamental pillars of this collection. Two examples to mention are Nestlé’s Condensed Milk, by Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, and Thé Rajah, by Henri Meunier.

Enric Batlló, textile industrialist, after whom a majestat in the museum is named

Batlló was an industrialist, a member of the family that founded the Can Batlló textiles factory in Barcelona, which later became the Industrial School, and a very generous collector and patron of the arts with a highly eclectic profile. Therefore, with the organization of the collections of the museums of Barcelona, pieces from the Batlló Collection can be found in the Museu del Disseny, the Museu de la Música and the Museu Nacional, among others.

In 1914, as Bonaventura Bassegoda mentioned, this collector made the disinterested donation to the Diputació de Barcelona of more than 900 pieces, 118 of which are now in the collections of the Museu Nacional. They include works by artists as renowned as Ramon Amadeu, Joaquim Vayreda and Manuel Pereira, among others. The majority of the pieces from the Batlló Collection in the museum are in the Renaissance and Baroque Collections.

Despite this, the best-known piece is the Batlló Majesty, a Romanesque majestat (crucifix) from the mid twelfth century that is named after the collector who loaned it permanently it to the Diputació de Barcelona in 1914.

Batlló Majesty, mid 12th century

Maties Muntadas, another representative of the industrial world

Muntadas was the proprietor of La España Industrial, but like many members of the bourgeoisie of the time he was also an art lover who knew the most famous painters of the day.

One cannot talk about the Muntadas Collection without referring to the Republican Generalitat’s task of safeguarding the artistic heritage during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), as Yolanda Pérez Carrasco did in her paper. When war broke out many private collections were promptly confiscated by the Republican Generalitat, which moved them for their safekeeping. The Muntadas Collection was taken from Barcelona to Olot, Darnius and Geneva, along with the works in the museum, which were also stored in Olot and Darnius. After the war, the collection was broken up and we can only speculate about the original number of pieces in the collection. In that period, much of the documentation was lost or did not in fact exist in the first place since many of the works were not considered important enough to be recorded.

Despite these vicissitudes, the Museu Nacional has in its collections about 200 works from the Muntadas Collection. Although its greatest contribution is Gothic, and it includes the names of artists as important as Bernat Martorell (Martyrdom of Saint Eulalia), Bernat Despuig (Altarpiece of Saint Anne) and Jaume Huguet (Virgin), some of the best-known pieces of Renaissance and Baroque art in the museum come from this collection too.

Outstanding pieces include Saint Candidus by Ayne Bru, or Triptych with Christ on the Cross, Saint Anthony the Abbot and Saint Catherine, by the Master of the Von Groote Adoration, which will appear in all their splendour in the new display of the Renaissance and Baroque Collection, which is due to be inaugurated at the end of 2017.

Francesc Cambó, the collector responsible for one of the most valuable bequests to the museum

The politician and patron of the arts Francesc Cambó bequeathed to the museum 50 paintings by the great European masters between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although it is by no means the most numerous contribution that we have mentioned, it is the most valuable disinterested contribution that the museum has received.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Ill-Matched Couple, 1517

The early Italians show the passage from medieval Gothic art to the Renaissance. The technical perfection of the Cinquecento is displayed in the paintings by Sebastiano del Piombo and Titian. We encounter great moments in the exuberance of Rubens with Lady Alethea Talbot, Countess of Arundel, the protestant satire of Lucas Cranach the Elder with The Ill-Matched Couple, and humour in Tiepolo’s carnival scenes, among which there is The Minuet. Finally, the details of modernity arrive with the two portraits by Fragonard, Jean-Claude Richard, Abbot of Saint-Non, Dressed ‘à l’Espagnole’, and Quentin de La Tour, Pierre-Louis Laideguive, and by Goya, with Allegory of Love, Cupid and Psyche and Manuel Quijano.

Cambó built up virtually his entire collection in less than ten years, from 1927 to 1936, with the advice of experts such as Bernard Berenson and Joaquim Folch i Torres. But although we know a lot about him and his collection, Imma Socias throws down the gauntlet and invites us to continue researching: where he bought, who his vendors were … still a lot of questions to answer that will never exhaust the subject.

Camil Fabra, the collector “of good manners”

Laia Alsina spoke about Camil Fabra, a member of the Catalan bourgeoisie, from a commercial and banking background, and also a politician. At the jewellers’ shop “Can Masriera”, they remembered the Marquise of Alella as one of their regular customers, and the balls at the home of the Marquis and Marquise featured regularly in the newspapers. Not for nothing is she the author of a Código o deberes de buena Sociedad (Codebook or Duties of High Society) and one of the most outstanding figures in the social life of Barcelona at that time.

The passion for Barcelona led him to leave his collection of 120 paintings to the city’s museums, works by some of the most important artists of the day. Thus, the 90 or so works from him that we have in the Museu Nacional have, in the main, enriched the Modern Art Collection.

Names stand out such as Josep Benlliure, Modest Urgell and Romà Ribera, and two singular works, recently incorporated in the new display of Modern Art: The Woman on Stilts and Fisherwoman, by Jan van Beers.

Jan van Beers, Fisherwoman and The Woman on Stilts, 1878

Collectors and artists at the same time: Eusebi Valldeperas and Josep Pascó

Of the Valldeperas bequest to the museums of Barcelona, 600 archaeological objects, only three have been located. We know the rest of them through the drawings in an album conserved in the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints.

In the Museu Nacional there are 200 academic drawings conserved, which illustrate his process of artistic training, as Francesc Quílez stated.

“I wanted to study a collector and I discovered an excellent draughtsman,” added Quílez.

Pascó, a draughtsman, poster artist and decorator, was also an eminent art collector, especially of fabrics, and a brilliant art teacher. He even taught artists like Joan Miró.

He was one of the Museums Board’s regular bidders and, as the very meticulous man he was, with his bids he always handed over a card presenting the work with as much information as he had about it, as well as photographs of the work to accompany it.

Unfortunately, though, we have none of the works from his private collection in the museum.

We do however have examples of his artistic side, with 14 of his works, which entered the museum in 1911, from another of the collectors who have been most important for the formation of the collections: Raimon Caselles.

Josep Pascó, Decoration on a book jacket, cover or frontispiece, around 1890

By way of conclusion, we see that there is a lot of research work and documentation. We at the museum wish to pay tribute to these collectors who have been crucial for the patrimonial wealth of Catalonia.

Related links

The persistence of a millionairess for the “Virgin of Sallent de Sanaüja”, Mireia Berenguer