Albert Estrada-Rius

The correct weight of coins, a matter of public order

Rulers have always claimed the power to guarantee metrological public order for the benefit of the common good. This means that it has traditionally been the authorities that have compulsorily established the system of weights and measures in force in transactions. This responsibility has been discharged with regulatory provisions that materialized in standards that, kept in the hands of the city council, were the original official models according to which measures, weights and scales had to be made for use in everyday life. It was necessary to control their quality and punish offenders; in fact, fraud in scales and weights was already being condemned repeatedly as a pernicious practice in the Bible. To this end the municipal post of weights and measures assayer existed in the principal medieval and early modern cities.

The scope of metrology is enormous and it has also had an important specific use in the field of coinage. Not for nothing, coins have in themselves traditionally been a system of measurement, being an official means of exchange and payment, as well as a convention for establishing the value of goods and services and a means of accumulating wealth.

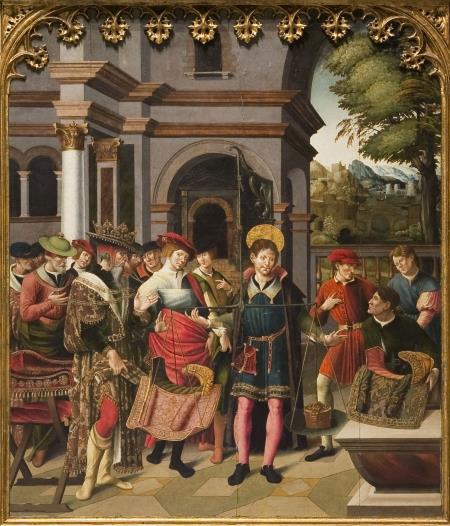

Manufacturing scales and weights for weighing coinage is an ancient practice. Weighing scales were already used normally for checking the ingots or pieces of gold and silver used as a measure of value in Antiquity, before coinage was invented. The Roman allegory of Coinage – the goddess Juno Moneta – was shown holding a pair of scales in her hand – something that has also become the symbol and attribute of Justice.

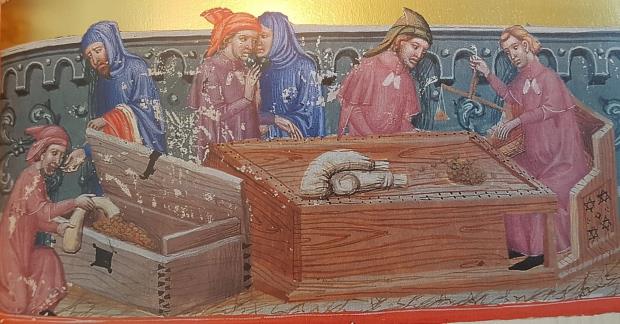

The valuable metal in coins has meant that their weight has throughout history been a fundamental constituent element that must be checked. The use of small scales and monetary weights to make this verification is well attested in the medieval Catalan tradition, in which they were called trabuquets. Thus, we have a record of scales and monetary weights in notarial inventories, in some artistic representations, and, of course, in the archaeological record. We even know that in late medieval Barcelona there was a public weigh master of gold florins in the Llotja de Mar, available to those who did not have their own scales or trabuquets.

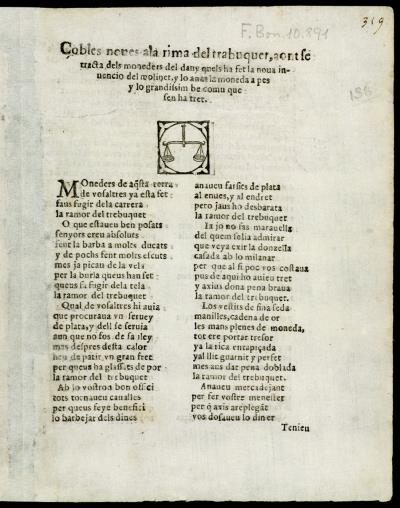

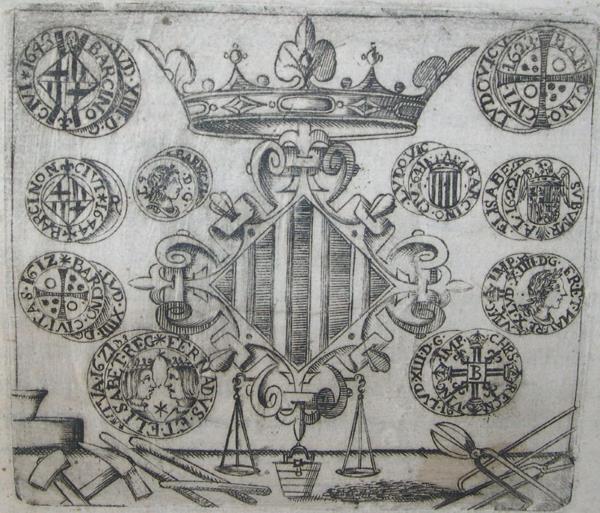

This use spread far and wide during the centuries of the early modern age to counteract the scourge of clipping gold and silver coins, and we see it in the many depictions of moneychangers in Flemish and Dutch painting of the 16th and 17th centuries. Even in the gravest moments of the crisis of falsification and manipulation of the coinage that Catalonia suffered in the reign of Philip III, some rhymes, cordel literature, were sent to the printing press in 1611, in honour of the scales used to verify the proper weight of coins in circulation.

Bourbon Barcelona, a centre of production of scales and monetary weights

If we focus our attention on the context of the coins entering the museum with the Tarradell donation, we have to start with the Bourbon reforms after the Decree of Nova Planta (1716). As a consequence of the abolition of Catalonia’s own coinage and the introduction of the Castilian monetary system, the outstanding, obligatory production of new scales and weights arose, as a result, above all, of the monetary edict of 1734.

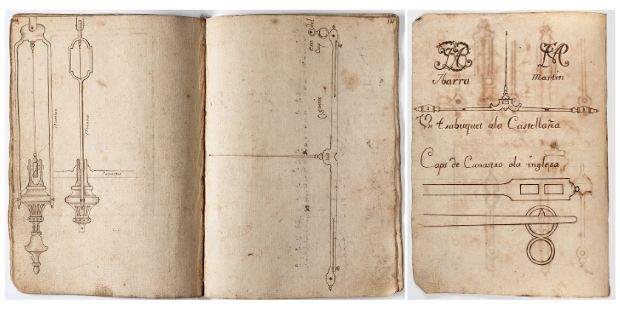

From this moment we can trace the appearance of a series of surnames, among which the Farriols family soon emerged, belonging to a group of master locksmiths specializing in the manufacture of these so peculiar pieces, part of a very large production of steelyards and other types of scales. In their work locksmiths used brass, wrought iron, silk cords, wooden boxes and labels printed in Spanish with the instructions for how to use the scales. The end result was the boxes that they sold and which the assayers hallmarked with a punch. In that period scales from Barcelona were exported all over Catalonia and beyond. This production lasted until the last quarter of the 19th century. Production was so great that even today it is not uncommon for many Catalan families to conserve a set of weighing scales handed down from their ancestors.

Metrological public order remained the competence of the new Bourbon city council, which, in this aspect, followed the model prior to the Decree of Nova Planta. In Barcelona, those charged with manufacturing weights and measures were an integral part of the locksmiths’ guild. In the city the guild brought together and regulated entry in the profession and the production to which it was dedicated, and it established the manufacturing prices. Moreover, the council appointed assayers who were responsible for verifying and hallmarking the coins minted. As a testimony to and guarantee of their verification, they punched the weights or the scales checked with a mark stamped next to the city’s coat of arms. The model continued throughout the 19th century despite the transformation of the guild system in the interest of free access to economic and professional freedom.

In Barcelona in the 18th and 19th centuries there were several firms manufacturing small weighing scales or trabuquets, made specifically for weighing coins, among other types of pieces, steelyards, weights and scales of all kinds. The surnames Barbarà, Crusats, Deops and Farriols refer to the assayers of measures, but also to the locksmiths with a manufacturing workshop and a shop open in the city. They were families of craftsmen with workshops in which they produced the scales and weights that they subsequently sold in the shops, and who also had their own shops, which became perfect showcases of their own products. Moreover, as a result of the guild system under the old regime, very much a closed shop, many of them ended up related to one another by marriage.

The conservation in the material from the Tarradell workshop of some pieces and documents from the old Farriols workshop, such as books of standards, accounts books and other materials, will enable us to reconstruct and evoke in detail a now forgotten system of production and working methods. The gradual end of the circulation of gold, replaced by banknotes and the spread of fiduciary money, saw the old weighing scales falling into disuse, ceasing to be made and falling into oblivion.

Related Links

Barcelona, a manufacturing centre of weighing scales / 1

Gabinet Numismàtic de Catalunya