Albert Estrada-Rius

We are approaching the conclusion of the exhibition Stories in Metal: Art and Power in European medals. Today we shall be talking about the 300th anniversary of the death of the Sun King, remembered through medals.

This autumn France has carried out several initiatives to commemorate, with all pomp and splendour, the 300th anniversary of the death of one of its most famous kings. Exhibitions, a television series and various publications have reminded us that Louis XIV the Great –the Sun King– breathed his last on 1st September 1715 at his most beloved home, The Palace of Versailles, which he had had built, involving all the arts, on deserted marshland. The king died ensuring his perpetual memory, thanks, among many other things, to the striking of almost 300 medals commemorating the exploits of his reign and also to the book that was published, his story in metal. The French Revolution was able to destroy the many equestrian statues of the sovereign throughout the kingdom, but it could not eliminate the huge amount of medals in circulation all over Europe.

The legacy of the king’s very long 72-year reign is huge and varied. Louis was the king of France and Navarre (1643-1715), but we must also remember that as a small child, upon the death of his father Louis XIII and while the Catalan Reapers’ War lasted, he was also temporarily the count of Barcelona (1643-1652). Moreover, as a result of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), he definitively annexed to his kingdom what is now known as North Catalonia – the county of Roussillon and more than thirty villages in the county of Cerdagne.

It is well known that the king made the most skilful and intense use of all the arts at the service of his absolute power and was the patron of many great collaborators who excelled at music, drama, literature, gardening and, in general, all the plastic arts.

All the arts were promoted to praise the king and France, as can be seen, for example, in the plot of the film Le roi danse (The King is Dancing, 2000). History also played its part and the sovereign made sure that the main events of his reign would be well remembered through various works of art. At Versailles, for example, painters immortalized some of these events on the ceiling of the Grande Galerie, or Hall of Mirrors, and in other areas too. The king’s story woven in a series of sumptuous tapestries in the Gobelins royal workshops was also very ambitious. However, no medium proved more useful for propaganda purposes than medals.

Indeed, a most interesting exercise is to compare some of the events dealt with in the three media referred to – paintings, tapestries and medals – in order to see how they were depicted respectively. To capture the message of the buildings, the monuments, the paintings or the tapestries, though, one had to be standing in front of the pieces. Because of their format, medals, like prints, travelled far and wide: everywhere they went they spread the king’s image at a fraction of the cost.

![Claude François Menéstrier, Histoire du roy Louis le Grand par les medailles [...] París, 1693, Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona](https://blog.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/Claude-François-Menéstrier-Histoire-du-roy-Louis-le-Grand-par-les-medailles-...-París-1693-Reial-Acadèmia-de-Ciències-i-Arts-de-Barcelona-1.jpg)

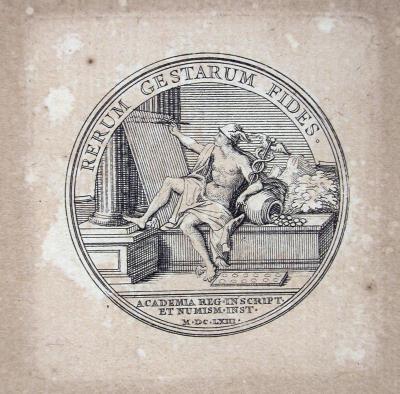

Striking a metal disc to turn it into a medal was an act that secured transcendence and immortality. The format of medals was timeless; proof of this was the Roman coins that were retrieved intact, while only fragments and ruins survived from the rest of the ancient world. The invention of the fly press in medal making made the endless multiplication of copies possible, and, in short, it turned the medal into a mass-produced art form akin to the chalcographic print. The series of medals made with fly presses in different metals could be used as diplomatic gifts. These heavy bronze presses, which in themselves are a work of art too due to their allegorical reliefs, are still conserved at the Paris Mint. To make them more realistic, while the event to be remembered is shown on the reverse, the king is shown on the obverse at the age he was when it took place. We can therefore see the changes in the king’s appearance from the tender age of four until his final years in a dozen different portraits.

Frontispiece of the book Medailles sur les principaux evenements du regne de Louis le Grand, París, 1702. Paris, 1702. An allegory of the story it contains about Louis XIV is depicted. In the background we see a fly press. CRAI-Barcelona University Library, from the Library of the Convent of Santa Caterina in Barcelona

The king decided to go down in history through the production of a series of medals in which each one performed the function of what would now be a still from a film. It was a long-term project and so he created a small academy to which he entrusted the supervision of the iconographies, the inscriptions and the plastic representation of everything. Very soon, though, his enemies, such as William of Orange and Charles VI of Austria, were forced to counteract these effects by striking their own series of medals. War through medals had come into being at the service of diplomacy and political propaganda.

Following the series, through the struck medals and the books that feature the engraved images and a printed explanation, allows us to learn about a great variety of events: births, marriage alliances, deaths, treaties, truces and diplomatic events, military victories, inaugurations of public works are all part of the thematic repertoire. Among them, linked directly to Catalonia, we can find the events referring to the above-mentioned Reapers’ War, the Nine Years’ War and, finally, the War of the Spanish Succession. The treatment is usually highly academic and classical with allegories and a constant recourse to mythology. At the same time, behind it we can also see a task of historical, geographical, etymological and heraldic research. Thus, Barcelona is alluded to through Hercules, its mythical founder, holding the coat of arms of the Ciutat Comtal, or the site of Tortosa on the banks of the river Ebre, to mention but two examples present in the exhibition.

Copies from the series in different diameters are also conserved in some Catalan museums, and by reviewing the old collections we can also discover individual pieces. In short, Louis XIV’s story in metal is no exotic exhibit; it has longstanding ties with Catalonia that the exhibition in the Museu Nacional helps to recover in the more general context of stories in metal as a unique European cultural manifestation, now virtually forgotten.

Gabinet Numismàtic de Catalunya