Artur Ramon

If we enter the Oval Hall – a huge ballroom without an orchestra – and go up to the next floor we come to the recently redesigned Modern Art collections. Here the discourse is both thematic and chronological. The MNAC is a museum of museums, like a Russian matryoshka doll. It is also the museum of Fortuny, and in the first room we find one of his masterpieces, painted in Rome: The Spanish Wedding. In it Fortuny shows us the scene of a marriage contract being signed in a Baroque church. The religious ceremony has finished and the bride and groom and the party of guests have gone into the rectory to sign. A procession of figures circulates, divided by social class: the upper classes accompany the bride and groom while those of more humble stock are seated. It is at one and the same time an apologia of costumbrismo and preciosity, a picture made up of fragments, of miniatures. This is how Fortuny created; in this register he felt comfortable, he was a painter of small and medium-sized formats. That is why he failed when he accepted the commission to paint a canvas measuring nine metres high by 30 metres long: The Battle of Tetouan. This painting is the story of a failure, as Fortuny was incapable of finishing it even after ten years, and the painting remained unfinished in his studio, hanging like a large tapestry.

The Spanish Wedding, Marià Fortuny, Roma, 1863-1865

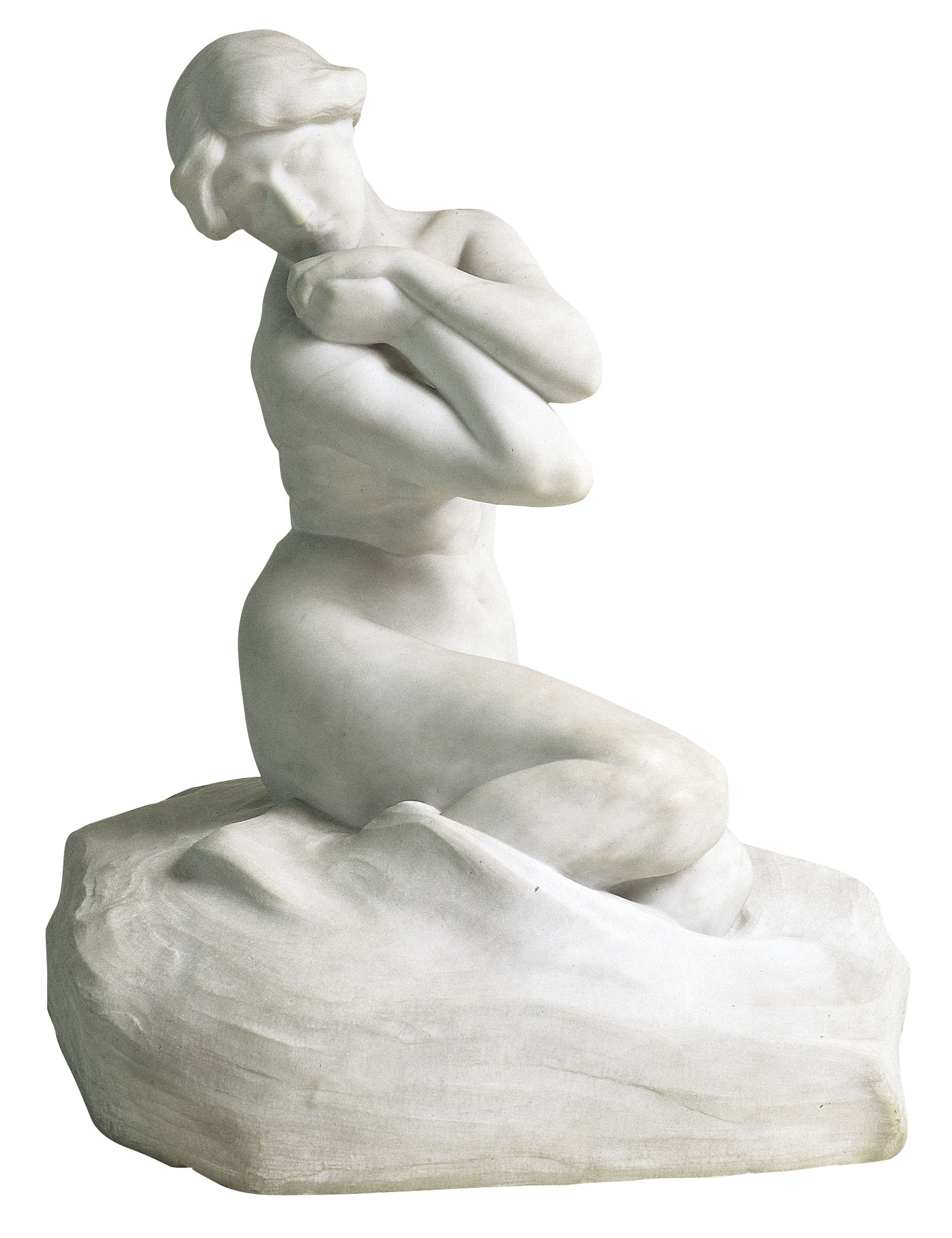

Going into the modern part of the museum is like travelling in time. We observe the different trends that make up nineteenth-century art. Orientalism had enormous influence over artists such as Fortuny, Tapiró and Signorini, who painted in Africa and sold the paintings in London and Paris, where there was a clientele crying out for this kind of art. After the Industrial Revolution, towards the end of the century a unique generation of artists appeared, the great masters of Catalan painting around the year 1900. In addition to the Modernista generation that featured Rusiñol and Casas in painting, and Llimona, Clarà and Clarasó in sculpture, a new generation burst on the scene, grouped around Els Quatre Gats, Pere Romeu’s tavern in Carrer de Montsió. There was Nonell’s miserabilism, his sad gypsy women painted in vibrant nervous brushstrokes, Mir’s landscapes full of fury and colour in Mallorca and Tarragona, and the nebulous ladies that go out into the night on the boulevards of Paris, by Anglada Camarasa, among others. Apart from the great masters of the turn of the century, there are valuable painters such as Francesc Gimeno and his bold painting; Marià Pidelaserra with his pointillist views of Montseny; Nicolau Raurich and his “matter” paintings that anticipate Miquel Vilà and Antoni Tàpies, and the delicate interiors of Pere Torné-Esquius, with a nod towards Vincent van Gogh and Félix Vallotton, among others. And we cannot overlook the designers of Modernisme, Gaspar Homar or Aleix Clapés, Gaudí and Jujol aside.

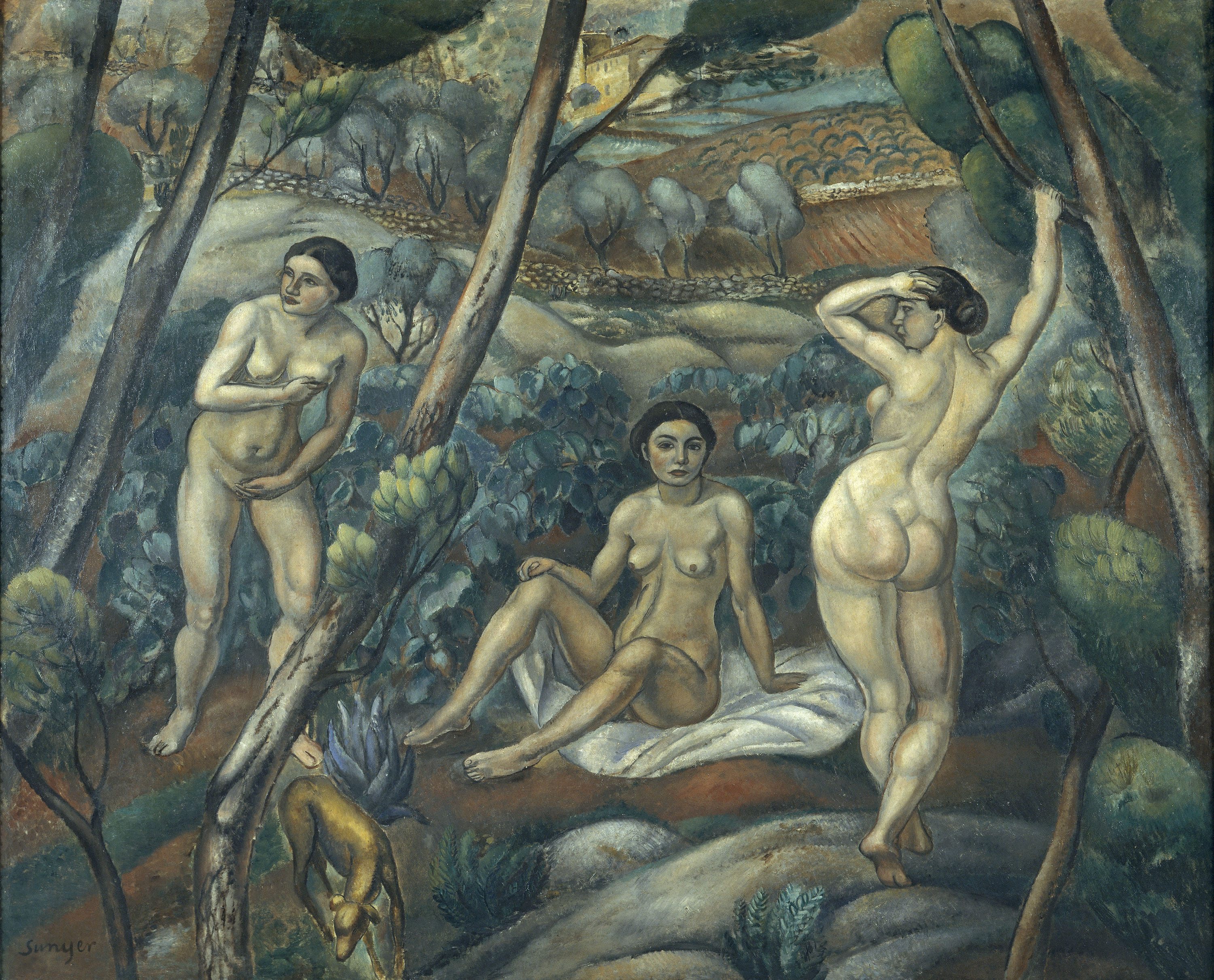

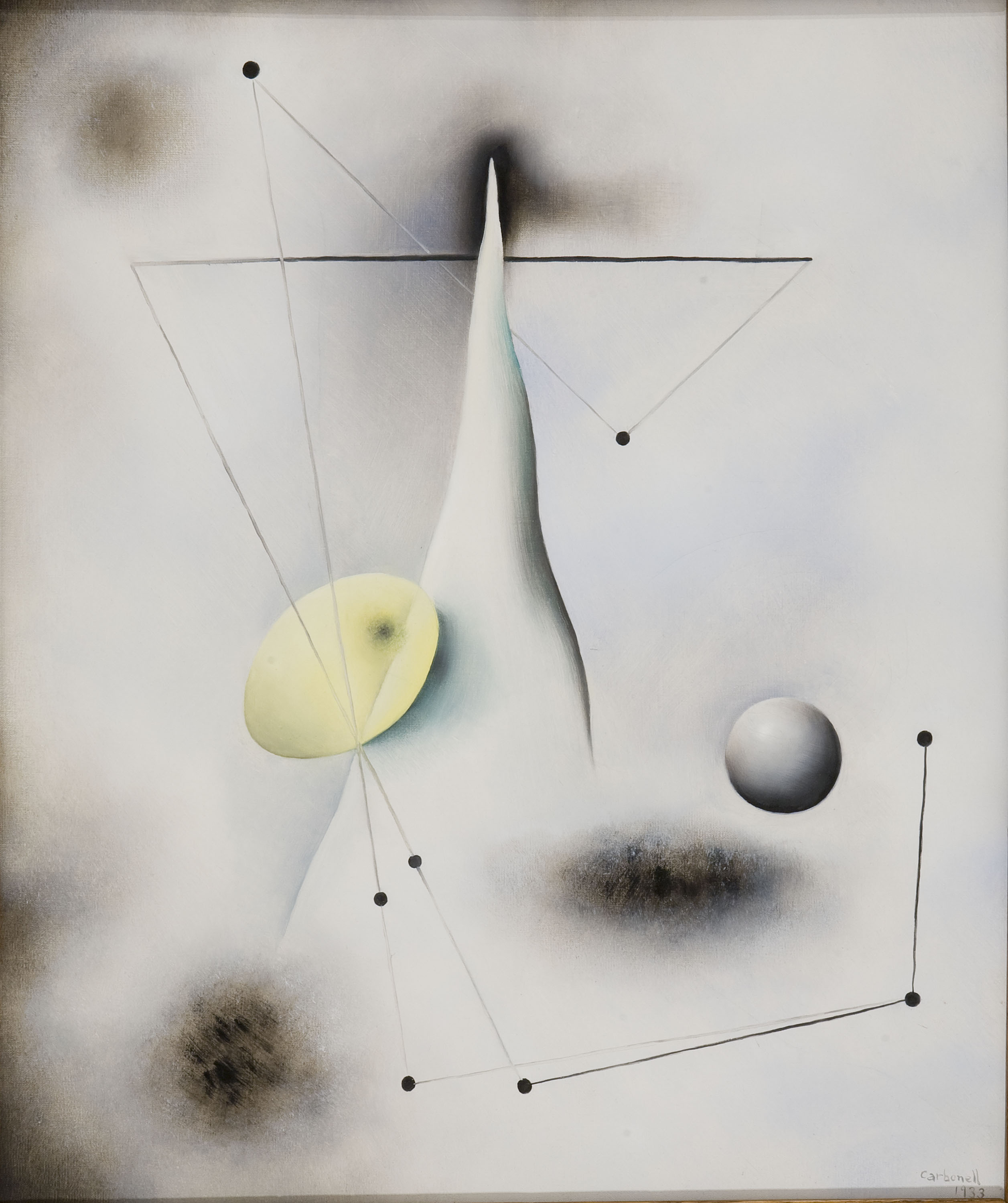

The reaction to the impressions of these artists would be the relaxed gaze of Noucentisme, the return to order and balance. Sunyer would be our Cézanne and Xavier Nogués the ideologue of a Mediterranean Catalonia, cultured and happy, expressed through his delightful satirical caricatures. The history of Catalan art is a contradictory toing and froing of action and reaction. After the calm of Noucentisme came the avant-garde movement, in the shadow of Surrealism. The group ADLAN imposed itself in the 1930s and created a dreamlike and poetic world with the abstract and geometrical compositions of Artur Carbonell, among others.

The Civil War, so well captured in the photographs of Agustí Centelles, closes a cycle in our art. After it nothing would be the same again. We end our brief visit with the portrait of Marie-Thérèse Walter, Woman in Hat and Fur Collar, by Picasso, which ties in with the memory of the Romanesque art that the artist saw for the last time on 5th September 1934, a few days before our museum was officially inaugurated.

.

Woman in Hat and Fur Collar (Marie-Thérèse Walter), Pablo Picasso, 1937

Artur Ramon

This text, based on the book Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya: un itinerari, is part two of the article published in thecorresponds to the second part of the article published in the Revista del Foment, núm. 2.145.