Francesc Quílez

On the verge of commemorating, next year, the hundredth anniversary of the acquisition of a workas emblematic as The Spanish Wedding, purchased through popular subscription, the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya has recently enriched its collection of works by Marià Fortuny with a new acquisition that corroborates the close relationship that, throughout its existence, the institution has maintained with one of the most outstanding artists in the history of European art.

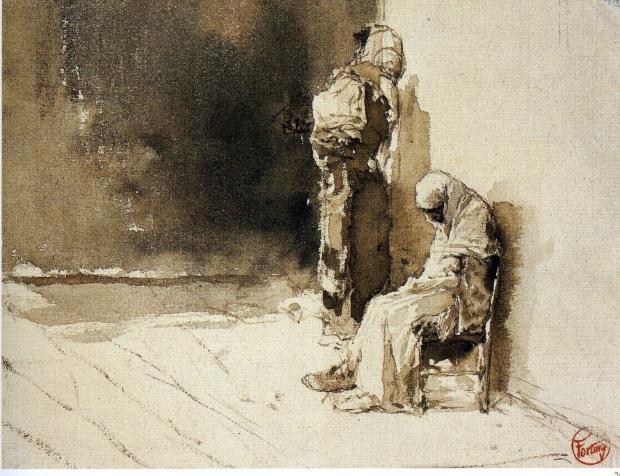

Two Beggar Women, a small-format work by Fortuny

The small-format painting Two Beggar Women confirms the characteristics of an exquisite method of working and an unequalled talent. In it the traits emerge that define a virtuoso style, that of an artist capable of promptly and effectively resolving any compositional challenge that he was faced with. The proof of his resolution can be found in his ability to generate beautiful optical sensations, of great preciosity even, and to do it most proficiently on a very small surface.

Although it may come as a surprise, especially to those not overly familiar with the artist’s work, the fact is that the size of this composition is nothing new. We know of a large number of works with this same peculiarity. After all, as I have previously pointed out on other occasions, Fortuny always felt most at home in small-format works that enabled him to display all his talents. In his case, without incurring in determinisms, or drawing hasty conclusions, the truth is that his creativity was usually channelled through tableautin compositions, those that most successfully embodied the figurative culture of a whole period and which best adapted to both the tastes and the aesthetic needs of a clientele which demanded that paintings should reproduce the luxury and the sumptuous ostentation that informed the system of values of the oligarchic bourgeoisie of the day.

In this respect, although it may seem paradoxical, it is useful not to forget that the artist was incapable of tackling the compositional challenges that, as in the case of the unfinished Battle of Tetouan, demanded a greater degree of exigency of him.

I had the opportunity to refer previously to a pictorial episode in which his capacity for resilience was put to the test and which ended, in canonical terms, in an obvious failure, since the painter was either unwilling or unable to complete the commission. Among the factors that I mentioned as a plausible explanation for this supposed lack of skill, I believe that his scant familiarity with productions of this kind crucially weighed heavily on him. In this case, a large-format painting always generated a discomfort in him that he could never overcome, and which culminated in a disjointed composition, comprising an assortment of isolated fragments lacking the necessary narrative unity.

Nevertheless, the work we are analysing here has to be framed in a different kind of group, as its nature is also different. Unlike some of his most popular paintings, for instance the abovementioned Spanish Wedding, or The Print Collector, these works seem to correspond more to a need for self-expression than to commercial reasons. It would therefore be an exercise for the painter’s own consumption, in which he would take the opportunity to give free rein to his most intimate creative urges, those that enabled him to channel his sensibility, to create and try out new ideas, focusing on motifs that, like the one depicted on the canvas, awakened a recurring interest in him throughout his career as an artist.

The Museu Nacional’s Fortuny collection, enriched

From this perspective, the already rich Fortuny collection conserved in the Museu Nacional is further enriched with a composition that, besides its originality, helps to diversify both the thematic representation and the physical type of the works. In this respect, the painting helps to reinforce an aspect that, unlike others, is not represented by many examples. As it happens, the museum has another painting of a similar nature that, while not completely unknown, has gone rather unnoticed, since it has enjoyed neither the success nor the prestige that the artist’s great iconic creations have. I am referring specifically to a small-format painting on wood entitled Moroccan Street, that both typologically and thematically shows a large number of elements similar to those in the work I am commenting on here.

Not for nothing, both works seem to correspond to the same objective, that of satisfying their creator’s interest in practising his ability to observe and depict what he is looking at, with his habitual mastery and naturalness. Moreover, in thematic terms, both productions show the same wish to depict street scenes, in which figures appear who seem to have been abandoned to their fate, whose poses highlight their resignation to the vicissitudes that fate has in store for them. They are therefore highly costumbrista and, from an orthodox point of view, we could define them as genre paintings and even examples of nineteenth-century pintoresquismo, even though they are far removed from the traditional stereotypes. We also see coincident formal aspects, as, in both cases, the painter achieves the optical effect of three-dimensional space, using light and colour as constructive elements. He moreover uses a wall as a habitual instrumental resource in his figurative repertoire, an identical solution, to enclose the composition

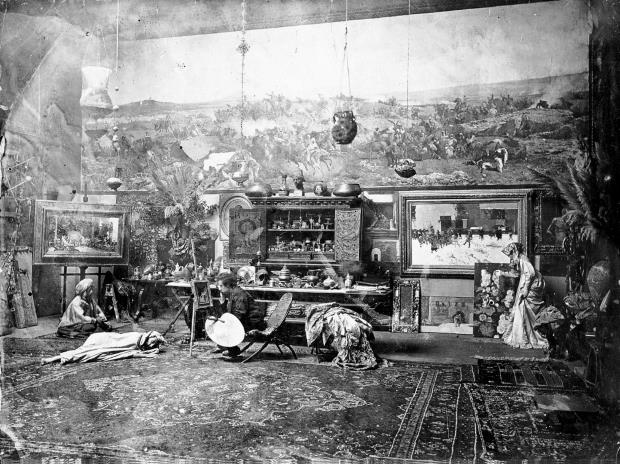

Fortuny’s journeys to Morocco, crucial in his work

However, aside from these coincidences, the element that differentiates them is the language. Moroccan Street is an extremely luminous production, a style for which Fortuny always felt a great predilection and on which he worked continuously. Incidentally, and on a curious note, it should be said that this work entered the museum as an element that was part of the painter’s work table, thus accentuating its nature as a mere divertimento. In this respect, although it may be a recursive cliché, the fact is that Fortuny’s journeys to Morocco, from 1860 onwards, were decisive for enriching his language, transforming his palette into a rich repository of colour and openly revealing his indebtedness to a landscape that irradiated an intoxicating light.

Although we do not know when this orientalist work was made, we can point out that, due to its shortcomings, observed in both the clumsiness with which he unevenly and rather unsuccessfully distributes the light all over the surface of the painting, revealing limitations most unlike him, and due to the rather unconvincing way in which he paints the human figures, which lack the firmness and gravity typical of him, it must have been made at an early stage of his career, somewhere between 1860 and 1862, coinciding with his first stay in Morocco, the experience of which was so crucial for his growth as a painter.

Fortuny’s gallery of outcasts and paupers

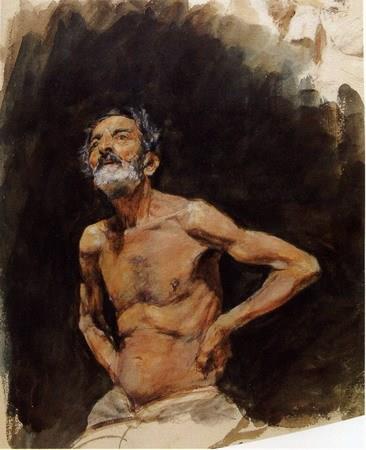

If we turn our attention to the object of my study, we can see a large number of differences, ranging from a far more sombre atmosphere to a skill for creating chiaroscuro effects, using light and colour as the elements with which he puts together a mysterious and hypnotic composition. The misshapen, almost grotesque features of faces that adopt a highly expressionist register also contribute unquestionably to this atmosphere. I will analyse some of these details below and attempt to note some of the interpretative keys that may shed some light on the circumstances in which it was made.

Despite the distance separating both creations, I believe that the miserabilist slant of the theme is an element that helps to pair them with one another. This trait is especially distinctive in the painting we are studying, since the protagonists, two beggar women, who appear in the doorway of what could be identified as a church, form an important example of a type very much present in Fortuny’s artistic career.

In this respect, although intermittently, the artist frequently moved away from the habitual themes and allowed himself to be captivated by ordinary everyday aspects, costumbrista motifs that were part of his existential reality. Far from incurring in the folkloric or pintoresco stereotype that had characterized the Romantic painting of the 1850s and 60s, his was a more true-to-life approach, which unquestionably helped to make his compositions more realistic.

This discovery of a far more sinister world – which casts a shadow over the luxury and the sumptuousness of his most characteristic works – reflects the appearance of new social groups that disturb the conscience of the well-to-do classes. In it we see beggars, paupers, destitute figures in a state of abject poverty and want, who fill of the streets of the cities and scrape together an existence in highly precarious conditions while subsisting on the money they obtain from the charity of some of the congregation attending religious services. Nevertheless, this group of social outcasts never once attained the class consciousness that might have awakened in them a desire for social rebellion against such an unfair situation. The fact is that the city increases these situations of inequality, that it impoverishes all those who are unable to integrate in the capitalist system and makes their life precarious, because they cannot sell their labour, and so they do not earn a salary that might provide them with minimal purchasing power.

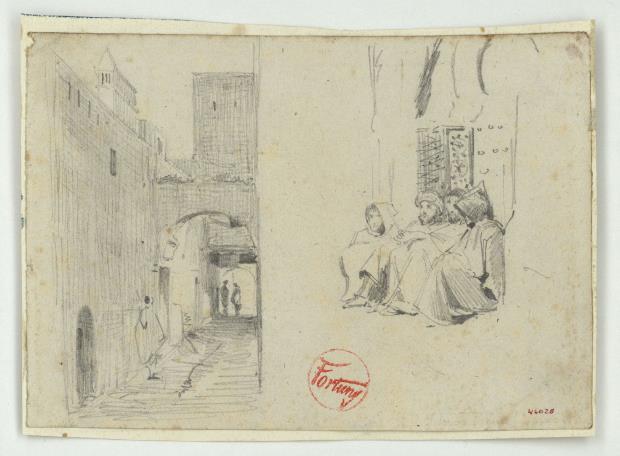

Fortuny’s experience of city life actually predated the onset of the great transformations of the late nineteenth century and therefore preceded the appearance of the social movements and working-class activism. This theme, therefore, which he assiduously developed during the years he lived in Granada, the extensive use of which is borne out by the large number of drawings he made when studying these figures, reflects the marginalization that was already part of the landscape of pre-capitalist societies, which had given rise to the appearance of groups of people who lived on the threshold of the most abject poverty.

In any case, for us the most important thing is how these motifs – because I would not go so far as to call them themes – clearly became prominent, and that, far from making them invisible or ignoring them, they fed his imaginary and nourished a large part of a figurative repertoire that habitually included nods to a type of human figure that, according to the mandatory canons, was included with the objective of providing certain narratives with greater richness and variety. In reality, the inclusion of this repertoire was merely a pretext for complementing and embellishing both the orientalist scenes, especially those set in the streets, and the costumbrista ones, including those in churches, or at the entrances to them, as was the case with The Portico of the Church of San Ginés, Madrid (The Hispanic Society of America). With respect to the former, they do present a singularity, a subtle difference, which it is necessary to mention.

In my view they include an ethnographic component, a catalogue of customs that, logically, due to their peculiarity, might be surprising. Swapping between the different disciplines, drawings, engravings and paintings, was a constant feature of Fortuny’s work, so much so that many of these figures regularly appeared copied in all three visual arts.

In the early etchings, made in the 1860s, for example Kasbah Guard in Tetouan, figurative groups emerge, arranged in such a way, with a contemplative attitude, that is very close to that of the group in Moroccan Street. These swaps also occur in some of his most famous orientalist watercolours, in which we discover nods, figurative loans that make up a visual repertoire that becomes repetitive. Indeed, productions like Faithful Friends (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore) or A Street in Tangiers (National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection) are perfect examples of the persistence of a commercial model based on these structural pillars.

Related links

«Non Finito». Fortuny and the paradox of the perfeccionist /1

Fortuny’s Carmen Bastián: problems with its reception and interpretation

Marià Fortuny: painting as the representation of a worldview

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats