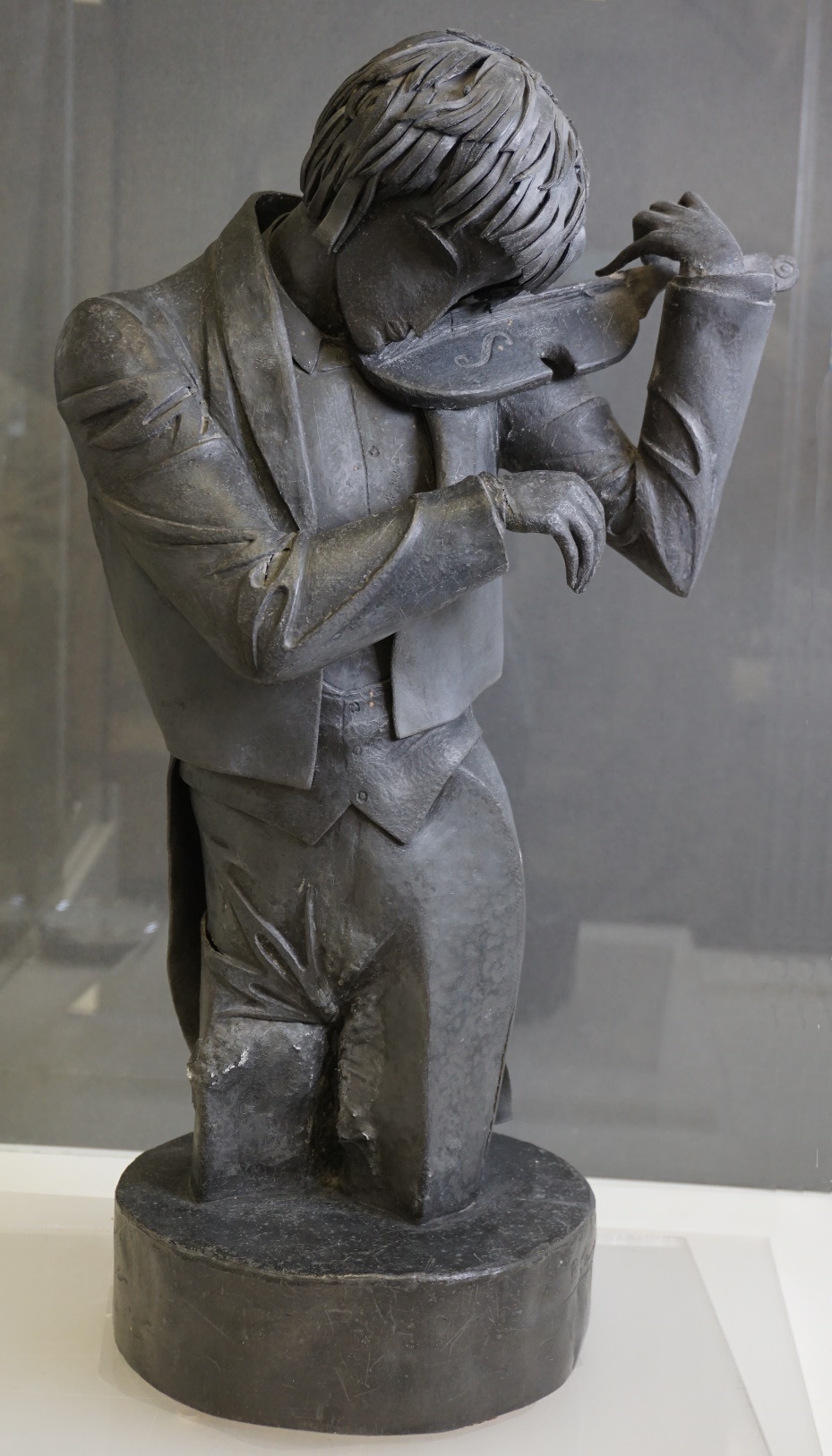

Pablo Gargallo’s sculpture The Violinist is suffering serious deterioration due to the incompatibility of the materials with which it is made: a wood armature covered with lead. For this reason, the Friends of the Museu Nacional have started a crowdfunding campaign Lets Save theViolinist. Conservator Àlex Masalles explains the details of the sculpture, the study process and the restoration needs.

At the museum, which has a large sculpture collection, Pablo Gargallo is heavily represented with works in marble and in metal.

Did you know that sculptures in public places in Barcelona such as, among others, the Olympic Horsemen at the Montjuïc Olympic Stadium, the Olympic Charioteers at Can Dragó, the Shepherd with Flute and the Shepherd with Eagle and Lamb in Plaça de Catalunya, or the sculpted scene of the Ride of the Valkyries on the arch over the front of the stage at the Palau de la Música Catalana are all by Gargallo?

Gargallo, a key artist in the history of modern Catalan sculpture, incorporated some of the ideas of the sculptural avant-garde into his production, for example the use of space and void as a constituent element of the work, and experimentation with new materials. Notwithstanding his modern approach, throughout his career Gargallo never abandoned the Classicist style, often related to Modernisme and Noucentisme, which he developed from his earliest days. Attracted by sheet materials, such as copper or lead, he sought new technical solutions and new formal approaches, although he continued making sculptures with traditional materials.

Pablo Gargallo in his workshop in Avenue du Maine in Paris (1928). © Fototeca.cat

Between 1920 and 1923, Gargallo worked with lead, incorporating this dense, ductile material into the construction of his sculptures, given its great malleability and the ease with which the pieces could be welded together. He created a total of nine sculptures experimenting with this metal, but The Violinist – the first of the nine – is the only one that has a wood armature inside it.

The Barcelona Museums Board purchased the sculpture in 1920 and the piece has been exhibited ever since. Successive generations of visitors have been able to see it in the city’s museums.

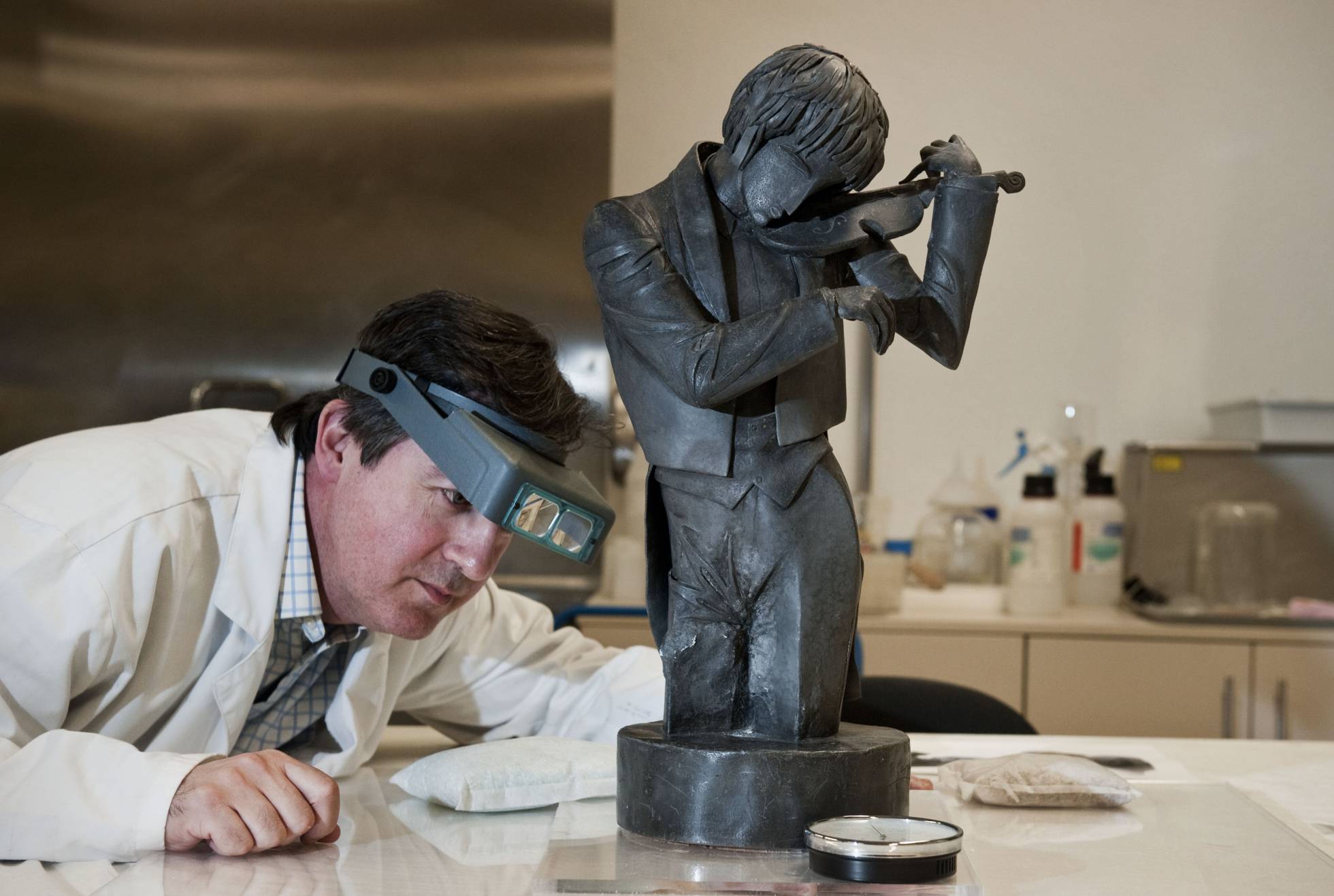

About twelve years ago a small swelling in the lead on the legs was observed for the first time. For a few years the changes in the sculpture were periodically monitored until, due to a gradual worsening of the condition of the lead, in 2010 it was decided to remove it from the galleries of the Museu Nacional’s permanent collection and place it inside a glass case in the inorganic materials restoration workshop, in controlled relative humidity conditions of less than 39% in order to try to slow down the changes as much as possible

Once in the workshop, we carried out an exhaustive, in-depth visual examination of the sculpture’s state of conservation, in order to diagnose the damage it was suffering and what the causes were. Besides the blisters appearing on the external surface of the lead on the legs and other parts of the sculpture, it was found that some welded seams had broken and the lead had been deformed. Some gaps had opened up through which the wood inside could be seen.

The presence of wood was obvious at the bottom of the base where the cylindrical block of pine that acts as the sculpture’s stand could be seen, and also behind the right-hand tail of the dress coat. The shape of the rest of the internal structure, hidden by the sheets of lead, was however unknown.

A study comparing contemporary black-and-white photographs – both those conserved at the museum and those lent by Mr Jean Anguera, Gargallo’s grandson – and the present condition of the sculpture has revealed that some important parts are quite misshapen, due either to an accident or to clumsy handling, something that considerably alters their original shape. Bearing in mind the fragility of the sculpture and the difficulty of moving it without causing deformations, it is not surprising that it has been taken out of the museum only on a very few occasions. Despite all this, however, the various moves that, during its history, the collection has had to make have inevitably included The Violinist.

The progress of the damage in the lead caused the blisters to burst. Underneath them a white substance that looked like plaster could be seen, whose composition turned out to be basic lead carbonate or hydrocerussite, the pigment known as white lead. There could be no doubt that the volatile organic vapours given off by the pine wood inside it were responsible for the corrosion of the lead through carbonation, a phenomenon that has been known for many years and which affects, among other things, organ pipes, numismatic collections and model ships.

Gargallo was obviously unaware that he was using two chemically incompatible materials: lead and wood. From the moment he finished welding the last sheet, inside the sculpture the lead began to be attacked by the volatile acids emanating from the wood, and this has continued without respite to the present day. It is a chemical reaction that has been working inexorably, even in the supposition that the wood has already ceased to emit volatile organic compounds

After doing several studies about possible treatments of the lead, using some pieces of lead from the Numismatic Cabinet of Catalonia affected by the same corrosion, it was concluded that the most suitable thing to do was to treat the lead in a cold plasma furnace in order to eliminate the products of the corrosion. A trial conducted in the plasma furnace of the IQS (Institut Químic de Sarrià) in Barcelona, on a model similar to the sculpture, confirmed for us that it was necessary to dismantle The Violinist before the treatment in order to detach the sheets of lead from the internal wood armature for the treatment to be effective.

Before this traumatic operation, not at all common in restoration work, it was necessary to learn about the materials and the construction technique of the sculpture, as well as the degree to which the inside of the lead had been affected by carbonation. The sculpture was taken to the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland where, thanks to a European research project, its entire volume was analysed with two non-destructive analysis techniques: neutron radiography and tomography.

A neutron image of The Violinist obtained at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland, in which the internal wood armature (in black) can clearly be seen

We now know that Gargallo made The Violinist with sheets of lead that were cut, cold forged, welded, and nailed and tacked onto a pine wood armature that acts as its support structure. On the head alone we have detected 22 nails attaching the pieces that form the hair. The wood armature was carved with gouges from a block of wood formed by three planks glued together and its shape is approximately that of the volume of the lead figure. You could almost say that the wood is “dressed” with a lead tailcoat.

The study with neutrons also enabled us to see how far the corrosion on the inside of the lead had gone. We estimated that 15-20% of the total internal surface area had been affected, far more than was at first thought.

Virtual 3D reconstruction in which the areas affected by carbonation of the lead on the inside of the sculpture are shown in red

With all the data obtained through the preliminary studies carried out on the sculpture we have been able to design a specific restoration strategy that will basically consist of:

- 3D scanning of all parts of the sculpture

- dismantling of the work to with minimum invasion of the original lead

- treatment of the lead corrosion in a cold plasma furnace

- elimination of the plastic deformations and repair of the losses

- replacement of the internal wood armature with a support made of an inert material, in the event it is scientifically proven that the wood continues to give off volatile organic compounds

- assembly and joining together of the parts

- construction of a tray for future handling and transportation of the work

- presentation of the sculpture in a passive conservation display case

Cost of the restoration work

It will be essential to use several industrial techniques, such as 3D scanning, computer numerical control milling, 3D digital printing and treatment in a plasma furnace in order to carry out the proposed restoration.

After studying various offers, the total cost of engaging the services of the companies that will take part in the different stages of the project is €46,000, a sum that does not include the museum’s conservation-restoration work, or the prior neutron radiography and tomography. The cost of these tests alone conducted in the Paul Scherrer Institute’s neutron reactor, necessary in order to learn about the inside of the sculpture, and to be able to quantify and locate the affected areas, would far exceed the amount calculated for the companies’ work.

We do not wish to renounce ever being able to exhibit Gargallo’s The Violinist again and so the Friends of the Museum, with their firm commitment to the conservation of the museum’s collections, have organized a crowdfunding campaign to raise the funds to enable us to pay for this complex intervention.

Enllaços recomanats

Restauració de béns culturals (vídeo del programa Arts i oficis, canal 33)

SOS para salvar una escultura de Pablo Gargallo, El País, 12 April 2016

Scientific study of The violinist by Pablo Gargallo

‘El violinista’ de Pablo Gargallo / ‘The violinista’ by Pablo Gargallo, video 04:17 min

Non-destructive investigation of “The Violinist” a lead sculpture by Pablo Gargallo, using the neutron imaging facility NEUTRA in the Paul Scherrer Institute, Physics Procedia, oct. 2014

Conservador-restaurador de materials inorgànics