Jordi Casanovas

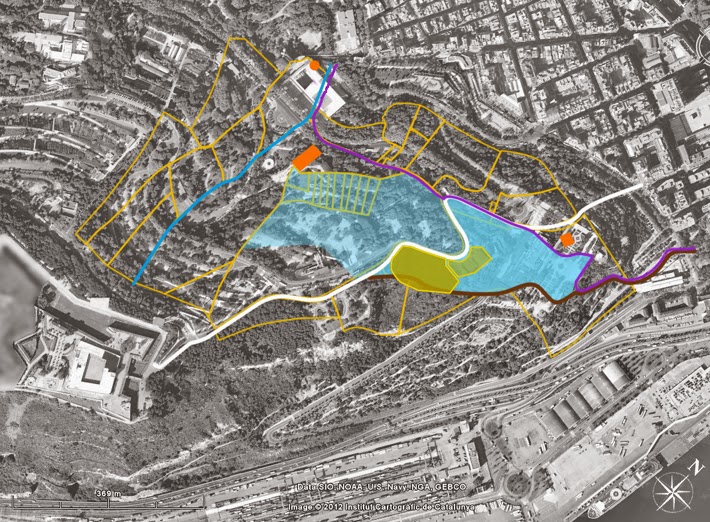

Source: An investigation extends the boundaries of the old Jewish cemetery of Montjuïc. Image: Dominique Tomasov

Surprisingly, once the Jewish cemetery had disappeared as a legal entity, and after intensive reuse of its gravestones as building material, the presence of large blocks with Hebrew inscriptions on them in one part of the mountain of Montjuïc still caught the attention of many people who were walking around it.

Hence the very long debate about whether the mountain was called Montjuïc due to an ancient temple dedicated to Jupiter (Mons Jovis) or to the existence of an old but more recent Jewish cemetery (Mons Judaicus).

The first vestiges

The first person to mention the gravestones was probably Luci Marineu Sícul, in about 1530-1533, when he stated: “I prefer to call it ‘Jewish’ because this is where they buried their dead and several gravestones with an inscription on them can still be seen.” Later, others such as Jorba, Pujades and Pere de Marca talked about it, also referring to “the Jewish graves that can be seen there with Hebrew inscriptions on them, although they are badly damaged after so many years”.

From the eighteenth century onwards one sees a growing interest, although in very small circles, in knowledge of the Hebrew language and the interpretation of its texts, in this case for those still on the mountain. In about 1752 Josep de Mora i Catà (1694-1762), director of the Academy of Belles Lettres in Barcelona, was the first to collect some of these inscriptions from Montjuïc in his house, and he also attempted to learn what they said.

In the nineteenth century the interest and the reasons changed and the Hebrew inscriptions went on to occupy a new space. Montjuïc with its Jewish cemetery was no longer a remote place and the incipient rambling associations organized numerous excursions to learn about the Roman and Jewish cemeteries, the flora, the minerals and the fossils.

Excursions to Montjuïc in the nineteenth century

Of all these visits to the mountain, the best known was probably the one on 12 November 1874, the report about which, made by Josep Fiter i Inglés, was first published in the magazine La Rondalla, and shortly afterwards in the Memòries de l’Associació Catalanista d’Excursions Científicas in 1878.

This excursion, very well organized, had the permission of some of the owners of the land on which the cemetery had previously stood and who later donated five gravestones found in the course of the visit.

From this same year, 1878, 6 January to be exact, we have a record of another excursion to Montjuïc with the aim of gathering fossils, molluscs and a few examples of roses (rosa catalaunica).

Hebrew inscriptions in museums

Throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Hebrew inscriptions timidly occupied a new, even more discreet place in the new museums that were being created in Barcelona. They were moreover reckoned with as an element to be taken into account in the shaping of our history. No longer was it a case of linking history and legend by any means, but of making it easier to understand with the aid of the archaeological elements to hand, a task far more complicated than was first thought.

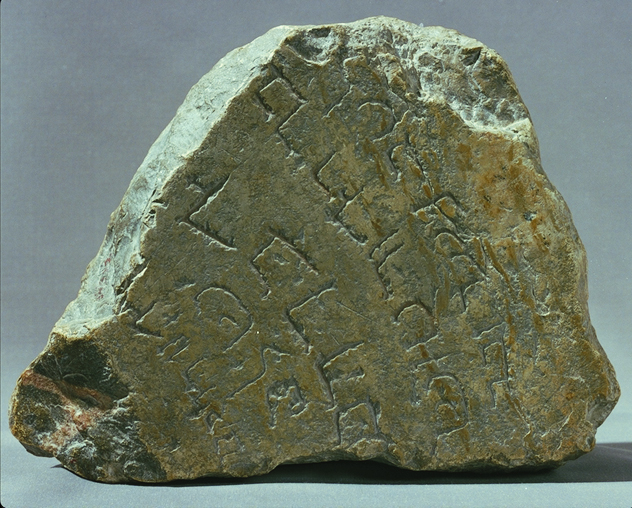

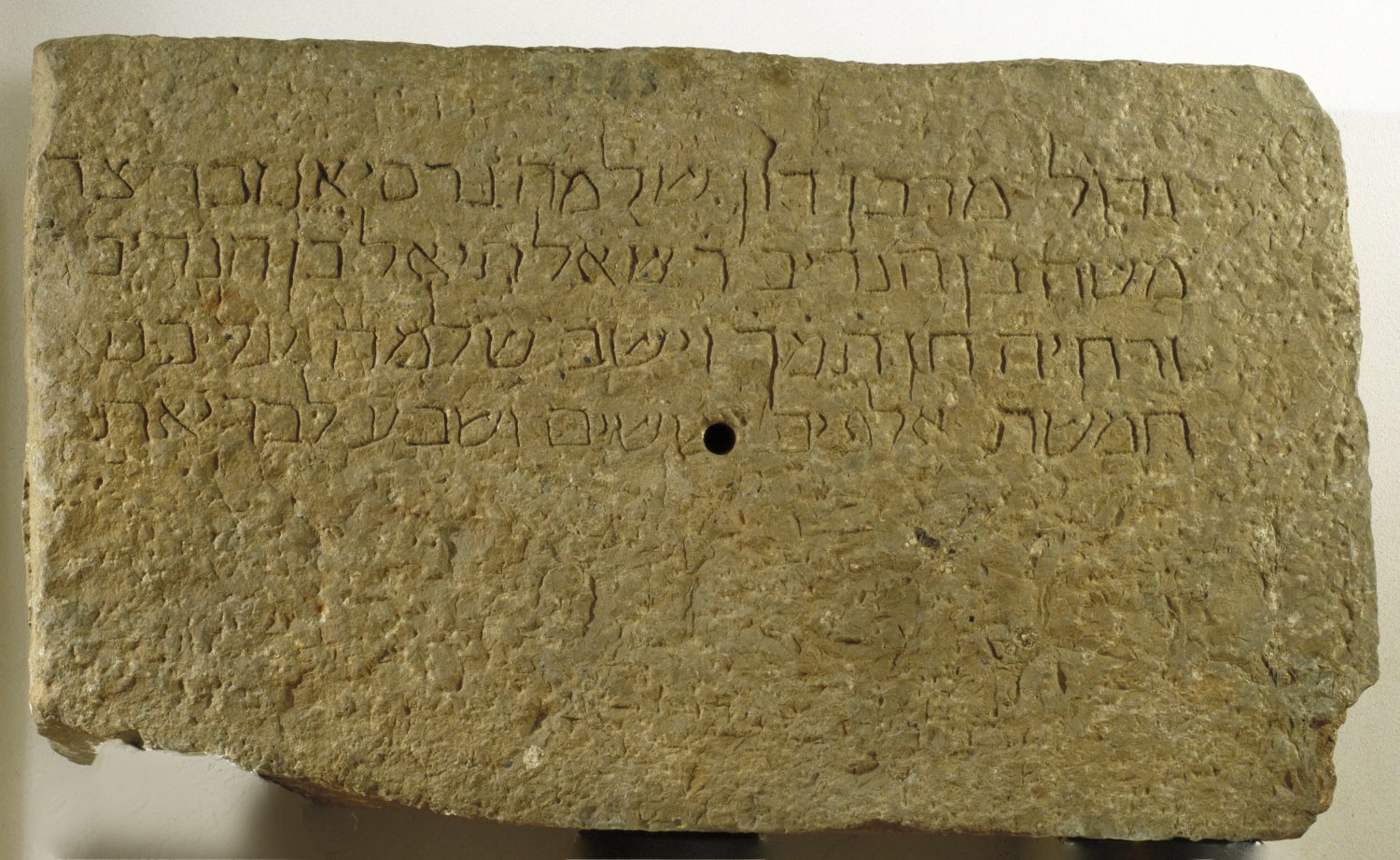

Besides the examples collected at different times on the mountain, it has been possible to record a fair number of Hebrew inscriptions in different parts of the city and the Metropolitan Area, reused as building material. Only a few have been found in the course of the two excavation campaigns in the cemetery, undertaken in 1945-1946 and 2001. On this latter dig it was possible to locate a dated gravestone (1229), still set on the original grave, something really unusual.

The reuse of old materials is a habitual practice in every period and place and it should not always be understood as a solution to the scarcity of materials from the quarries. It is the consequence of a very active market in reused materials, resulting from the many demolitions, and the agents tasked with putting them into circulation.

In our museum the presence of Hebrew inscriptions has been a phenomenon that we might describe as isolated. Two of the inscriptions were later temporarily incorporated in the Romanesque and Gothic rooms in 1995 and 1997 respectively for the purpose of explaining the importance of the Jewish presence in medieval society. The inscription placed in the Gothic room was probably the best-documented epigraphic element in the entire collection. It is a large piece with the epitaph of a personage well known from the documentation, Salomó Grasià, who died between 1306 and 1307, data that very seldom appear. Both inscriptions are now in the MUHBA, Museu d’Història de Barcelona, one of them exhibited in the ground in Plaça del Rei.

Difficulties due to incomplete documentation

At the present time in Barcelona there are 109 Hebrew inscriptions recorded, of which only 19 were complete or almost complete and 90 were fragments of varying sizes, something indicative of the state in which this material reaches us and the difficulties with studying it.

If we add that only 14 inscriptions have the date indicated explicitly we realize that it is very complicated to achieve any kind of systematization. Of these 109, 17 have disappeared but some mention of them, a documentary reference, a drawing or a photograph, is conserved. In very few cases are they sufficiently representative fragments; most of them have scant epigraphic significance, with few data to make it possible to reliably record their reuse and the date when it took place.

This lack of precision with regard to the mechanisms of reuse also makes it hard to set guidelines to make new locations possible, since even with a clear record of the use of materials from the Jewish cemetery in a particular place it might not be possible to identify any fragments, whilst in other cases it has been possible to find new ones without any prior documentary reference to hand.

Examples of finds

There are four very representative examples that are most useful for explaining this situation. They are the Portal Nou and the chapel of Nostra Sra. de la Canal, the excavations of Baixada de la Canonja, the Lieutenant’s Palace and the Palace of Valldaura.

King John I made a donation, in 1395, for the building work on the chapel of Nostra Sra. de la Canal, of 30 stones from the Jewish cemetery of Montjuïc. We know that by the beginning of the seventeenth century the chapel was already half in ruins. Restored, it would seem, in about 1607, the gateway and the chapel were badly damaged as a consequence of the events of 1714, and for this reason they were demolished in 1854. In this case we have been unable to record the real presence of Hebrew inscriptions in their construction.

In the course of several excavations with the aim of finding the body of Saint Peter Nolasco made between 21 April and 30 August 1788 in Baixada de la Canonja, several objects, columns and piles were found near the Cathedral plus a Hebrew inscription of which only a transcript of the text on a sheet of paper and an odd translation have been conserved. The aura of legend that surrounds this work and the fact that the gravestone has not been conserved make it difficult to draw conclusions.

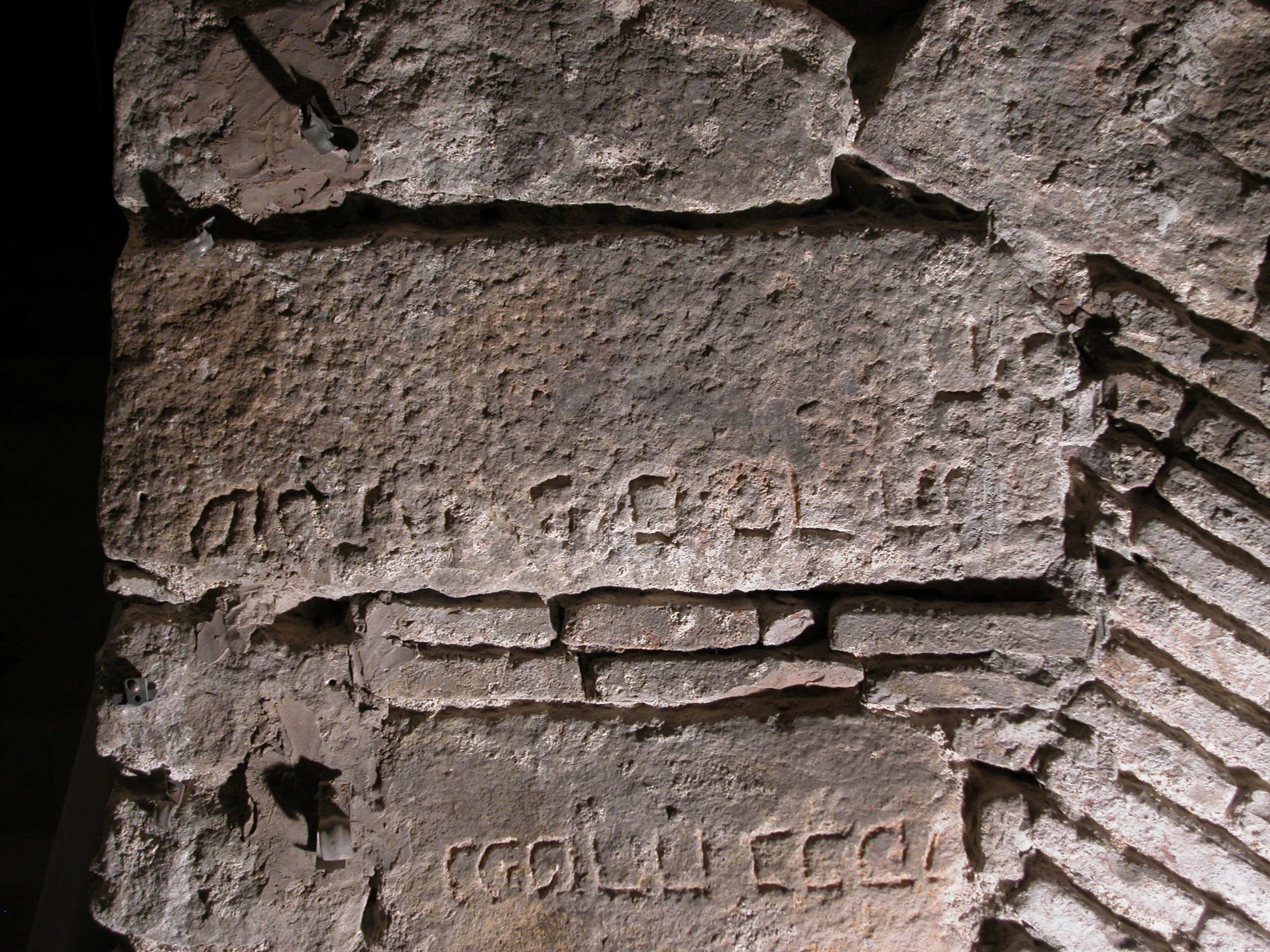

Up to now the most representative example is the Lieutenant’s Palace, a sixteenth-century building between Plaça del Rei and Carrer dels Comtes de Barcelona where it has been possible to locate 33 fragments of Hebrew inscriptions from Montjuïc that had been reused in different parts of the building.

Last identified fragment in this same front during the intervention in 20002, which corresponds to the square top of the previous image

Finally, in the place where the Palace of Valldaura once stood we have identified six more fragments. This palace was built on the site of an earlier Cistercian monastery, Santa Maria de Valldaura (1150-1169), on Collserola inside the modern-day municipal boundaries of Cerdanyola del Vallès, becoming a place of rest and a hunting ground of the kings of the Crown of Aragon from James II (1291-1327) to Martin I (1396-1410). King Martin I enlarged and embellished this property between 1400 and 1407. During its long decline, in the fifteenth century, specifically in 1475, ownership was transferred to private individuals as a royal donation. In this case we have no documentary references mentioning the reuse of stones from the Jewish cemetery, despite the presence of these six fragments; nor do we know in what part of the palace ruins they were located.

The 61 fragments found in the city of Barcelona are mostly concentrated around the Cathedral, the Episcopal Palace, the convent of Santa Clara and excavations in Plaça del Rei and Carrer Comtes de Barcelona, as the most representative core. Beyond this point there are some isolated finds in nearby places, the most recent being that of a fragment in the roof of the church of Sants Just i Pastor or the one that was found in the old convent of Sant Josep, where the Boqueria market now stands.

All these now decontextualized materials appear either clearly reused, or they are invisible with the inscribed side out of sight unless the wall or the surface where they are found is dismantled. Their reuse as ashlars, parts of doors or windows, voussoirs in an arch, paving stones or simply as visible or invisible filler material allows us to conclude that there was no wish to destroy or hide them, but simply to make a profit from them in the easiest way possible.

Related links

The Jewish Cemetery of Montjuïc in BarcelonaCenter of Studies ZAKHOR, 2008 (pdf, 214 Kb)

Registre i investigador d'inscripcions hebrees