Mariàngels Fondevila

The exhibition Xavier Gosé, 1876-1915. Iillustrator of modernity allows us to take a look at the figure of a professional profile in between the 19th and 20th centuries, linked to media interests. And, at the same time, it allows a tour to be made of some of the aspects of the Belle Époque accompanied by a cicerone of exception, Xavier Gosé.

The magazines: the new exhibition room

The technological advances and the new systems of mechanical reproduction, without forgetting the enactment of the new press law, helped to foster the increase in the illustrated magazines which benefitted from a certain climate of freedom of expression. The satirical French magazines, which could be bought in the newsstands of the Rambles and reached the Quatre Gats, “livened up the artistic life from the end of the century in the midst of the torment and academic routine of the school of La Llotja”- in which Gosé studied with Nonell, Torres-García or Joaquim Mir- and the illustrations of Toulouse- Lautrec or Steinlen were, according to witnesses, the “trophies they kept in their pockets”. Very soon, the Barcelona, Madrid, French and German magazines would feature a treasure trove of images of Gosé: on the covers, on the centre-page spread, on the back covers, coinciding with the artists mentioned above, as well as with Cappiello, Juan Gris, Kupka, Marcel Duchamp, Van Donguen, Valloton, Caran d’Ache, Pau Roig, Juan Cardona, Galanis, Paul Iribe, Leon Bakst or Georges Lepape, amongst others.

Dandy versus Rapin

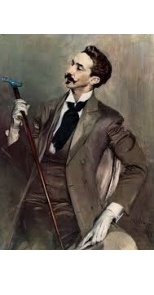

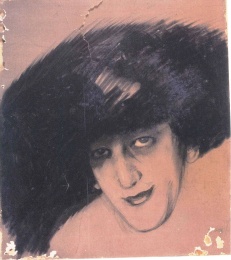

Different testimonies from the Quatre Gats, where in 1899 Gosé put on his first exhibition of charcoal drawings and watercolours of proletarian aesthetics, where a young promise would auger well, being remembered as distant artist: “He was more likely to be taken for a store assistant for women’s clothes than as an artist!” For sure, the portrait that he did of Ramon Casas pointed more towards the ways of a dandy of Montparnasse, where he would live from 1900 to 1900, than a rapin with a baggy corduroy jacket from Montmartre. The neighbourhood began to stop being the legendary refuge of the eccentric bohemian artists: the cravats and long hair were no longer prestigious. Strictly speaking, Gosé wasn’t either of the same style of his contemporary exhibitionist and provocative dandies such as, for example, Jean Lorrain, for whom he illustrated a book, Gabrielle d’Annunzio or Robert de Montesquieu.

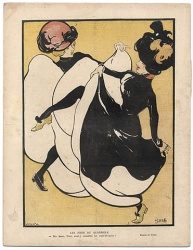

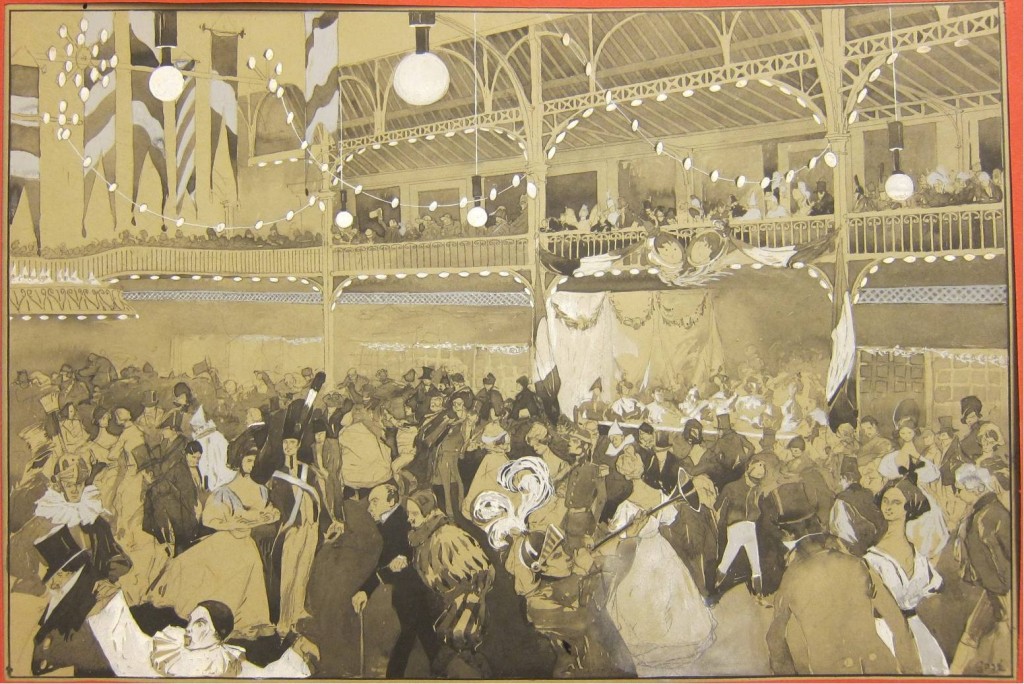

Moulin Rouge

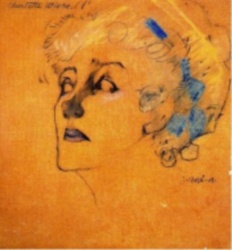

Xavier Gosé lived the nightlife of the Moulin Rouge to the full, and contributed to perpetuating its memory. In 1902 Oleguer Junyent explained in a letter to his elder brother Sebastià, at that time in Barcelona, that he had been to a party dedicated to the nineteenth century artist Gavarni with Gosé and that they had gone in fancy dress. The two artists had arrived home exhausted after singing and dancing until the early hours of the morning in that famous venue run by a Catalan, Josep Oller. His first drawing published in Le Rire presented two dancers in the peak moment of the dance, the can-can. He also dedicated portraits to the dancer Charlotte Wielhe and did a series set around Spanish dancers who made a successful debut in the venues of this famous uproarious temple.

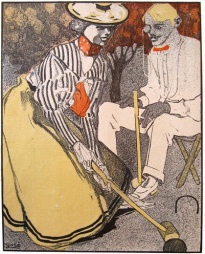

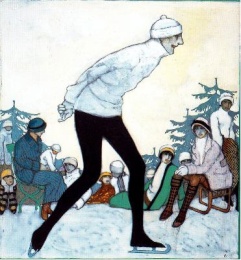

Les sportsmen

As well as portraying women swallowed up by the indolence, the dolce far niente and disturbing teenagers, Gosé depicted the dynamic life of the sportsmen in Los Deportes, Pèl i Ploma, Femina and ridiculed them in the monographic L’Assiette au beurre. On the occasion of his illustrations in this magazine, which was famed for not paying, he received payment in kind in the form of a bicycle.

Once back in Barcelona, Gosé would continue the cycling fashion, and, like Pere Romeu (who practised fencing) or Ramon Casas (the tandem), he was a sportsman. He was a friend of the footballer André Puget who would become a second-class soldier and who died in combat in the Great War.

Furthermore, Gosé captured the spirit of the new icons of modernity, such as the automobile industry; the heroes of aviation (Bleriot, Wright or Santos Dumont). And we shouldn’t forget the horse racing of Longchamp, sanctuary of the gallop and the backdrop for the promotion of fashion; the Palais des Glaces (The Ice rink) in the Champs Elysées, full of elegant young ice skaters, as well as new dances such as the Black American dance, the cakewalk or the Tango, imported from the suburbs of Buenos Aires by the nouveau riche who had settled down in Paris, and that provided Gosé with his best snapshots.

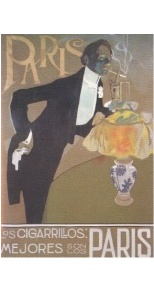

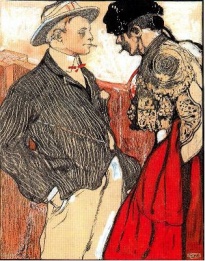

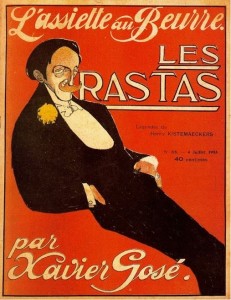

Les rastas

In the cosmopolitan Paris of the Belle Époque, pell-mell of nationalists, the rastas were those individuals of an exotic race, often Latin Americans, who lived a high level lifestyle, and of whom their origins or means of their existence are unknown. In the venue Ambos Mundos (Both Worlds) of Barcelona, frequented by Gosé before leaving for Paris- as remembered by an anonymous writer of La Vanguardia– you could already find him having dinner each night with champagne with some nouveau riche doing everything he could to relate with the high society.

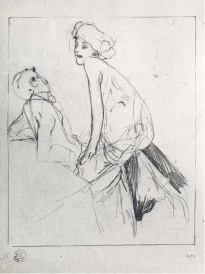

Cocotte

During the 3rd Republic, Paris was a tolerant city which was proud to exhibit scantily dressed women and venal love from the Bella Otero, Lilian de Pugy or Cleo de Merode. The prefecture of the police registered a total of 24,000 prostitutes, an extreme that could be seen in one of the dark sides that Gosé would capture in his watercolours. Gosé would take care to represent the prostitutes de luxe in the search for new sensations: the cocottes, the grisettes or the demimondaines, the expression behind which you can find the origin of the work of Alexandre Dumas, son, Le Demi-Monde. Opium and cocaine, moreover, circulated in the artistic circles of the workshops of Montparnasse.

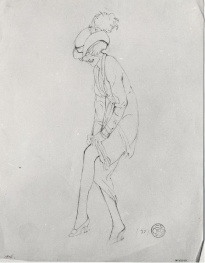

Fashion

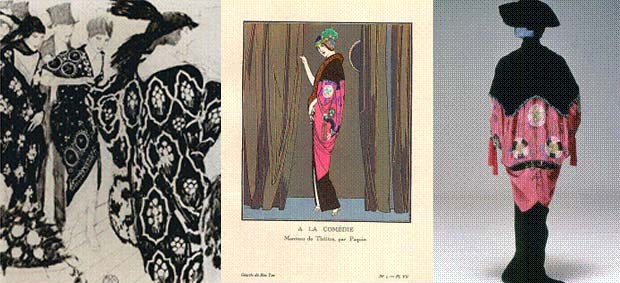

The critic, Vauxcelles, considered Gosé to be an illustrator with very good taste, with a major fantasy and a sense of the silhouettes of the women of the time. From 1912 onwards, the Gazette du Bon Ton, a precedent of the American Vogue and Le journal des dames et des modes, were the fort of his tall and slim mannequins that would prefigure the Art Deco, which would be dressed in the clothes of Jacques Doucet; the English and sports fashion of Redfern; Worth, who didn’t conceive producing a dress devoid of opulence; or Madame Paquin. At the same time, Gosé published his own fashion designs which were permeable to the oriental fashion of the fascinating couturier Poiret, who catalysed the spirit of a whole era through fashion and the decorative arts.

Tuberculosis

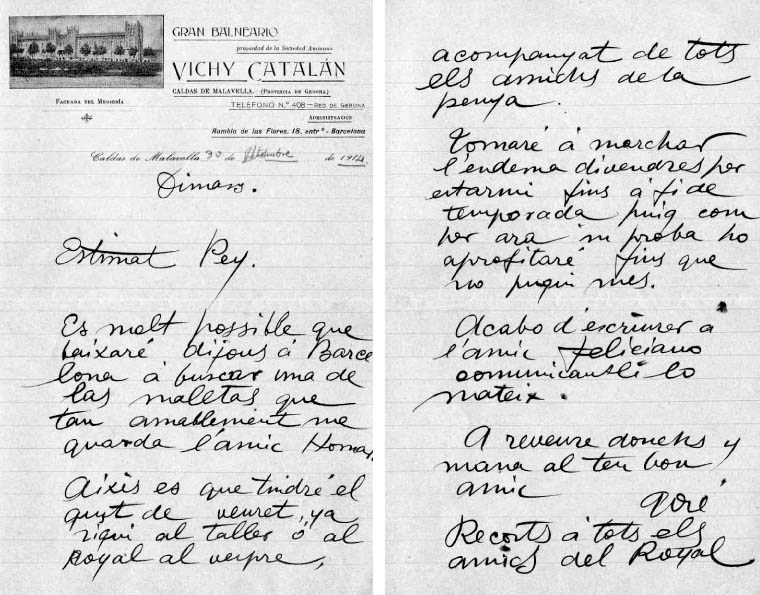

Gosé was affected by the most deadly illness of the 20th century: tuberculosis and, for this reason, spent long periods in the spas such as the Grand Hotel du Parc in Vitel or the Vichy Catalan Spa of Caldes de Malavella, where he went in 1914. There he hoped to get over his illness by means of rest and the purifying thermal waters, which unfortunately didn’t work given that he would die in Lleida just a few months later. In 1911 the South American writer and artist, Abraham Valdelomar, wrote a disturbing story, entitled La Ciudad de los Tísicos (The Tubercular City), which took as its starting point the work of Gosé.

Art Modern i Contemporani