Dr. Xavier Sierra i Valentí

This text is an extract from the article «The altarpiece of Saint Anthony the Abbot, ergotism and the Antonians» that Xavier Serra i Valentí published in Gimbernat: Revista d’Història de la Medicina i de les Ciències de la Salut, 2021, vol. 75, p. 169-180.

Altarpiece of Saint Anthony the Abbot, by the Master of Rubió. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

In the Gothic art rooms of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya you can find the Altarpiece of Saint Anthony the Abbot, by the Master of Rubió. The author is an anonymous and enigmatic artist, active in Catalonia in the last third of the 14th century, who was given this name due to his most outstanding work: the Altarpiece of the Church of Santa Maria de Rubió.

The Altarpiece of Saint Anthony, dated between 1360 and 1375, is a work of Italian Gothic style, of unknown provenance, which was acquired by the museum in 1948. It has dimensions of 173.5 x 176.3 x 11.5 cm and is painted in tempera and gilded with gold leaf on wood. Only the body of the altarpiece is preserved; the predella and the dust cover have been lost.

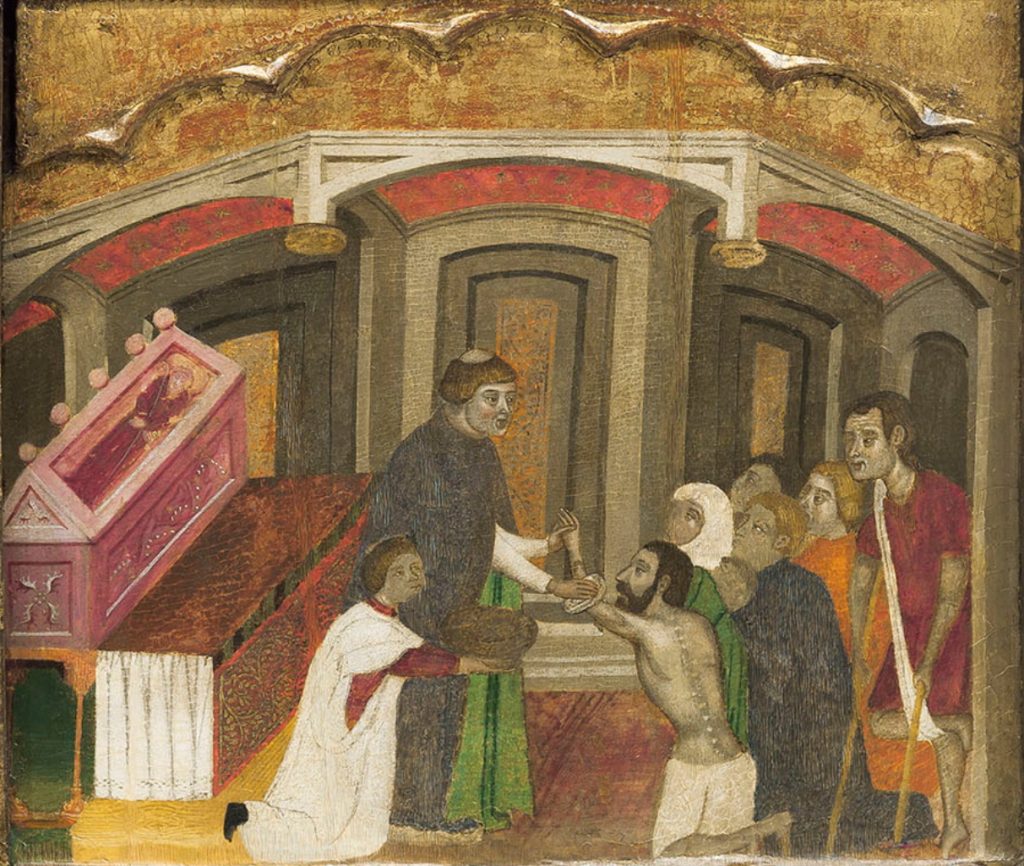

The work is dedicated to Saint Anthony, represented in the central panel and on a larger scale compared with the rest of the panels. The saint appears standing, toned and with a long beard, dressed in a black habit (probably in reference to the habit of the Antonians) and holding a book in one hand. In the other, he carries the abbey staff, a symbol of his ecclesiastical dignity. Above this central panel is a Crucifixion. The side panels refer to various episodes of the life of the saint; we can see a young Saint Anthony giving alms to the needy, the temptations he was subjected to during his retirement in the Thebaida Desert, the demons hitting him, Jesus indicating the way to follow or the joint preaching with Saint Paul the Hermit. But the scene we are most interested in is that of the lower compartment of the right-hand panel, in which a priest is represented (toned and dressed in liturgical clothes) treating the sick suffering from the disease, the so-called Saint Anthony’s fire, to whom we will dedicate this comment. One of those waiting to be attended is carrying crutches, which indicates that the lower limbs are affected.

Saint Anthony’s fire was the name given to the Middle Ages to ergotism, also known in some places as the holy fire, a name with which it appears in many Medieval Portuguese Galician songs. Ergotism was an intoxication caused by the moldy rye, a parasite fungus of this cereal (claviceps purpurea), and a very common pathology in the Middle Ages. The word ‘ergotism’ is derived from the French word ergot, which is used to designate the rooster spur, and indicates a long and conical shape, like a horn. The spikes of the parasitic rye have a small black horn.

Claviceps purpurea (left); An ergot body that has germinated to produce lever structures that release sexual spores (right)

Black bread, made from rye or mixed with other cereals or acorns, was the main food of the lower classes, while white bread was reserved for the upper classes. By grinding the mouldy rye, you get a dark reddish powder that goes unnoticed when mixed with the dark flour of the cereal. The alkaloid that causes the poisoning is ergotamine (from which lysergic acid is derived), which caused hallucinations, convulsions and arterial vasoconstriction that could lead to tissue necrosis and the appearance of gangrene in the extremities, with the consequent amputation of the limbs.

Since ancient times, mouldy or contaminated rye, ergot of rye, has also been used to cause abortions. In the mid-nineteenth century, the active alkaloids of the fungus began to be known and it was observed that they could be used pharmacologically, because due to vasoconstriction, the hemorrhages of the birth could be stopped. Dudley and Moir isolated ergometrine in 1932 and showed that it had uterotonic agents.

Lower right-hand panel of the Altarpiece of Saint Anthony the Abbot, by the Master of Rubió. On the left, you can see the tomb of the saint, over an altar. A clergyman cures the sores of a patient while others wait their turn.

There is evidence of various epidemics of ergoticism, documented from the 9th to the 17th century, which generally coincided with bad harvests and with periods of famine. In these circumstances, farmers had a very poor diet, which was probably limited to some polluted black bread croutons. The last major epidemic of ergotism in Europe took place in France in 1951.

Clinically two forms of ergotism can be distinguished:

- Acute ergotism, characterised by strong spasmodic seizures in limbs with paresthesias. This form is more documented in northern Europe.

- Chronic ergotism, in the dominant aspect, is an intense peripheral vasoconstriction. The disease began with a sense of intense and sudden cold in the limbs, which later becomes a sense of internal burning. It is for this reason that it was also called the disease of the burning or internal fire. The ischemia of the legs could lead to the dry node with thrombosis or in vasculopathies in the extremities, such as ears, nose or fingers. The necrosis of the affected area was generally over-infected and could entail amputation.

In all cases, ergotism was accompanied by high fever, complemented by strange views and hallucinations. Among the alkaloids of claviceps purpurea have been isolated substances related to the lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which explains this disorder. Other symptoms that can be observed in some cases of ergotism are sedation, hypotension, hypotony, vomiting, headaches, paraplegia and, occasionally, heart attack. Death occurs in 10-20% of the cases.

Apart from the altarpiece we discuss, many other works of art represent cases of ergotism. In other altarpieces dedicated to Saint Anthony the Abbot, such as in Pere Garcia de Benavarri, 15th century (Harding Collection in Chicago), we find mutilated characters with leg prostheses (probably a reference to ergotism).

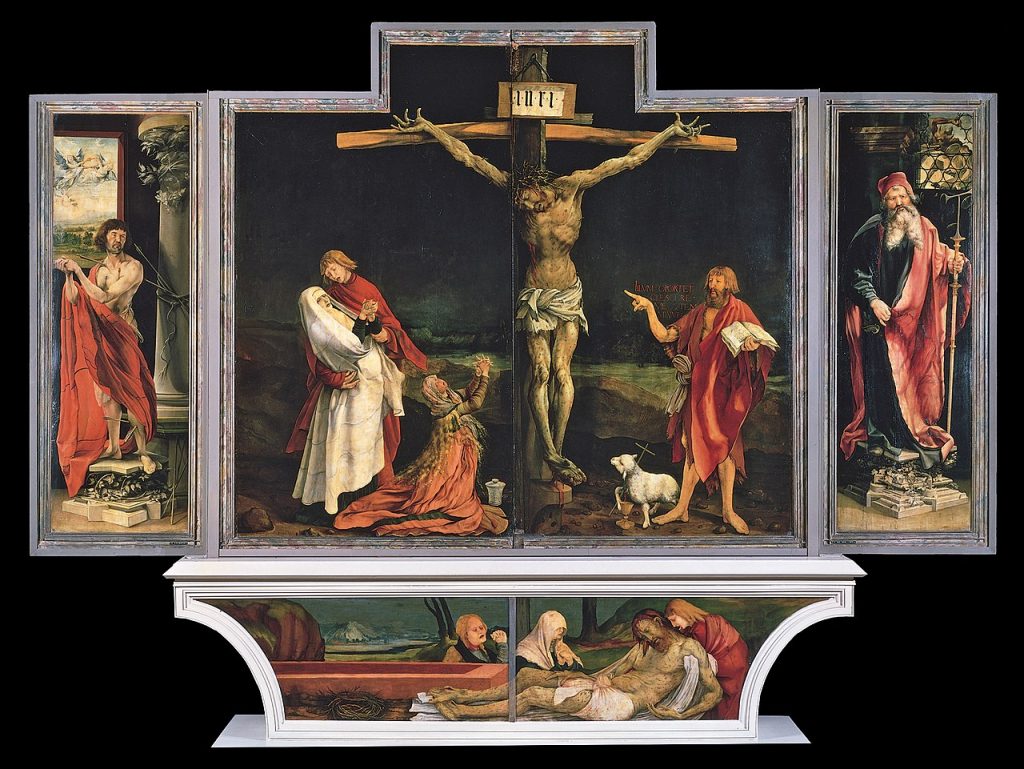

The contractions typical of this pathology have also been represented in various works of art. Among them, it is worth mentioning The Crucifixion of Christ by Mathis Grünewald, from the Antonian convent in Issenheim, where you can appreciate the skin lesions and the characteristic dystony in one of the characters. On the other hand, the figure of Christ, twisted like those suffering from ergotism and with a terrible expression of pain, is probably inspired by the patients who were taken care of in the hospital of the Antonians.

Issenheim Altarpiece, Mathis Grünewald, 1512-1516

The painting by Hieronymus Bosch has been repeatedly studied to represent cases of ergotism; Several mutilations appear and the use of crutches.

Photo of the Temptation of Saint Anthony by Hieronymus Bosch, 1501

We also find allusions in ergotism in the Cantigas de Santa María (The Canticles of Holy Mary) by Alfonso X of Castile and the miniatures that illustrate this text in the Rico codex. In Romanesque times, we can also see ergotism in the modillons of some Romanesque churches, such as Javierrelatre, which make an allusion to amputated limbs as a result of this pathology.

The order of the Antonians

Returning to the altarpiece of Saint Anthony and in the scene of the priest who is healing a patient suffering from Saint Anthony’s fire, it is necessary to comment on something about the order of the Antonians, the clergy who were engaged in curing people suffering from ergotism.

It is for this reason that it is necessary to go back to the arrival of the body of Saint Anthony in Europe. The remains of the saint were transferred, first of all, to Alexandria from the Thebaid desert (the place where the saint lived and died) in the late 6th century and, about a century later, in Constantinople. In 1070, Jocelyn de Châteauneuf and her brother-in-law Guigues Disdier, a native of the Delfinat, took them to his hometown, a village that was then called “The Motte-au-Bois”, halfway between Grenoble and Valence. Pilgrims would soon arrive at the saint’s tomb, following the custom of that time to pilgrimage to places where relics of saints were worshipped to ask to be thaumaturgically cured. It was disseminated that the saint would cure what in France they called the illness of burning or Saint Anthony’s fire. So much was the influx of sick of this disease that the Benedictines of the Monastery of Montmajor (near Arles) were commissioned to found an abbey in the village, which has since changed its name and was called Saint-Antoine-l’abbaye (Saint Anthony the Abbot).

In 1095, the young French nobleman Guérin de Valloire, who suffered from Saint Anthony’s fire, promised to devote himself to the care of the sick if he managed to be healed. Once the miraculous grace was obtained, he and his father Gaston founded a small community of lay people, “the company of the Brothers in alms”, under the protection of Saint Anthony. Grouped in a hospital, they cared for the sick who suffered from this disease.

The order was approved that same year by Pope Urban II, taking on the name of the Order of the Knights of Saint Anthony (Canonici Regulares Sancti Agustini Ordinis Sancti Antoni i Abbatis), popularly known as the Antonians or Antonites. Their habit was black with the blue tau letter on the chest; and some authors believe that, this letter, which appears everywhere as a symbol of the saint, referred to the crutches used by the sick of ergotism.

Thus, the first Antonians were a community of lay people and were linked to the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Antoine-L’Abbaye until in 1218 they were recognised as a monastic order by Pope Honorius III. In 1248 they adopted the rule of Saint Augustine and in 1297 Boniface VIII recognised their own canons, by the papal bull Ad apostolicae dignitatis. From that moment on, the community took on the name of the Order of Saint Anthony or Canons Regular of Saint Anthony of Vienne. But the relations between the Benedictines of the Sanctuary and the Antonians had been clouded and often conflicting, so the Pope decided to resolve the differences by expelling the Benedictines from the monastery, forcing them to settle in the Abbey of Montmajor and granting them the exclusive custody of the sanctuary and the relics to the Antonians, who had to pay a rent to the Montmajor abbot of 1,300 pounds per year as compensation.

Habit of the Canons Regular of Saint Anthony of Vienne.

And this is precisely what the Master of Rubió’s altarpiece represents: an Antonian canon who, with the help of a schoolboy, washes and cures the wounds to a sick person suffering from Saint Anthony’s fire, during the course of a ritual in front of the saint’s tomb, which appears on the left, in reference to the relics of the home of the Order, in Saint-Antoine-l’abbaye.

Expansion of the order of the Antonians

Shortly afterwards, the community expanded and opened more hospitals in various places in France, Italy and, especially, in Flanders and Germany. They also opened houses in Sweden, Cyprus, Constantinople and Athens. The congregation had a great boost during the fourteenth century, when it also had to attend to bubonic plague, or Black Death, patients, as the community, in addition to the cases of ergotism, served many other diseases, especially Erisipela, which was often confused with ergotism. By the 15th century they had 370 hospitals and orders, with more than 10,000 monks, and some prominent ecclesiastical personalities came out of the order. Among their privileges was to look after the sick of the Roman Curia.

The Antonian hospitals were very austere. They usually had a kitchen with refectory or a place to make meals, a bedroom, the chapel and some service facilities. They were used to lodge pilgrims and patients, but over time, the care of patients ended up being the primary task of the establishments.

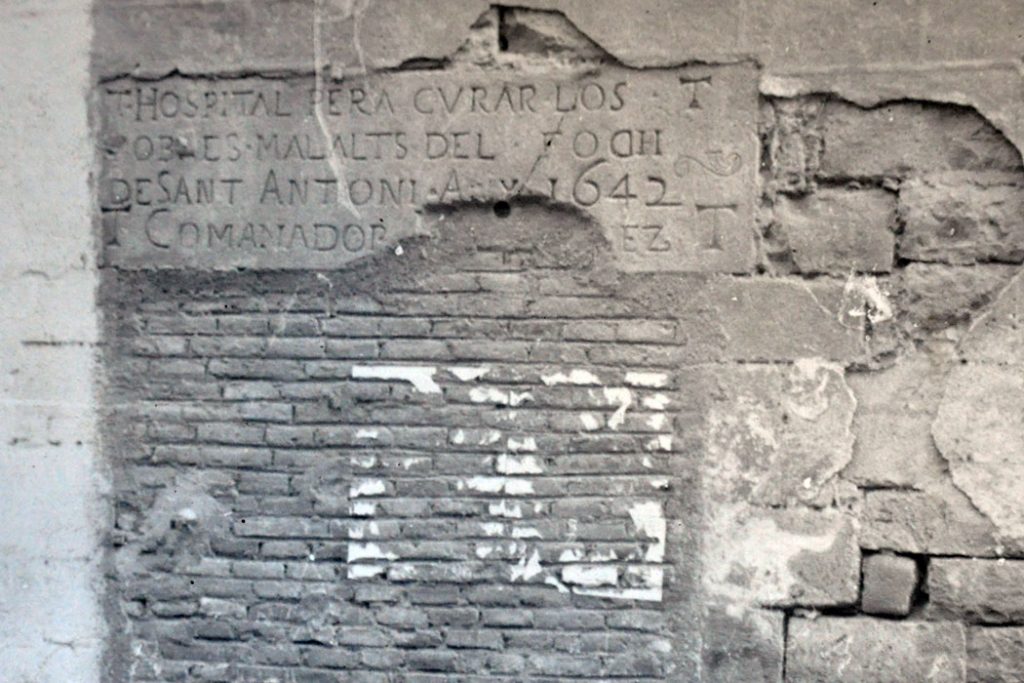

In the Iberian Peninsula they had already been established since the 12th century in various towns of the kingdoms of Castile and Navarra and along the Camino de Santiago de Compostela (St James’ Way), highlighting that of Castrojeriz (1146), that by privilege of Alfonso VIII was granted to the pilgrims, and which was the headquarters of the Commanding Major and General Preceptor for the Crown of Castile, Portugal and, later, of the West Indies. Gradually, hospitals were opened in many other cities in the kingdom of Castile. In Navarre, in 1274 the order of Olite was opened, the convent-hospital that was the seat of the General Command of the kingdoms of Navarre and the Crown of Aragon. In the Catalan lands, the Antonians founded hospitals in Cervera, where they arrived in 1215, and, later, in Lleida (1271), Tàrrega, Valls (1313) and Perpinyà (1319). The last establishment was in Barcelona, in 1430.

They also founded hospitals in Valencia and Oriola. The community of Mallorca settled in the city the same year of the conquest, since King Jaume I gave them some houses on Carrer Sant Miquel and other possessions in Inca. In the 15th century, the church of Sant Antoniet de sa Porta (so named because it is located next to one of the gates of the wall) came under the control of the community of Antonians.

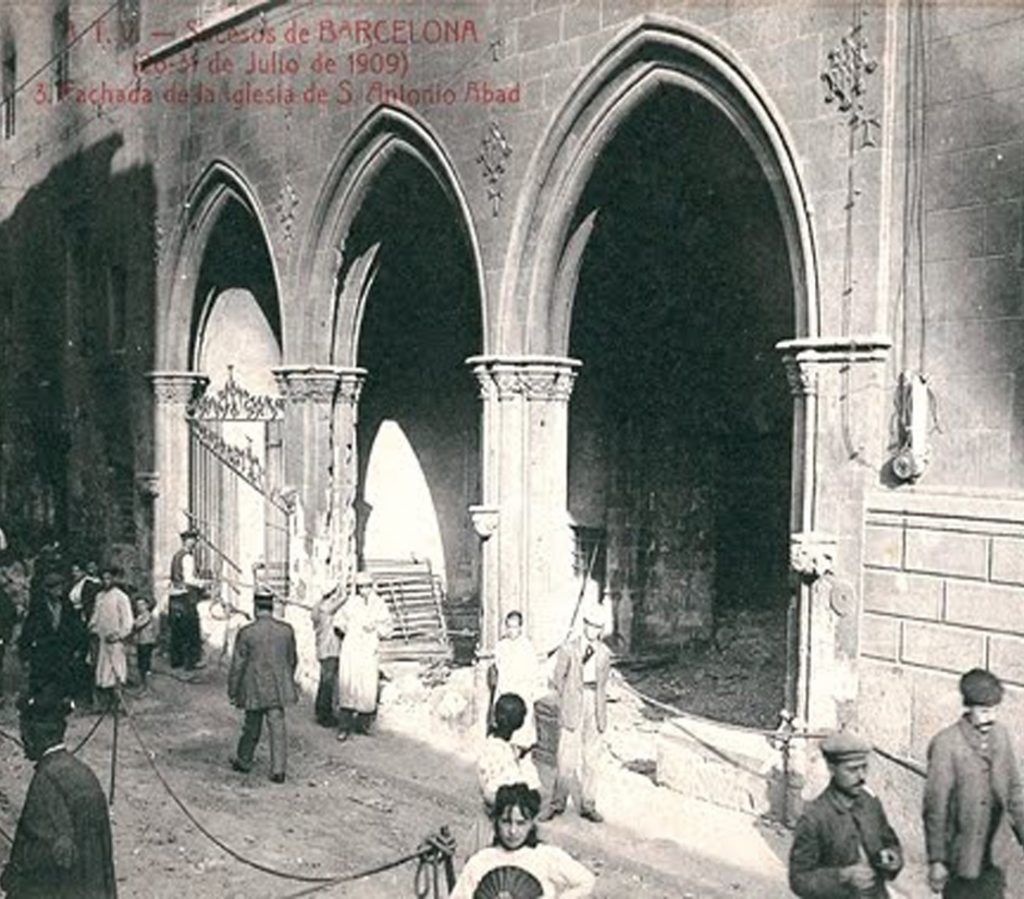

The Antonians did not arrive in Barcelona until the 15th century, and settled near the portal of the western wall, where they built a hospital, a church and a convent in 1430. They were in charge of health control of strangers arriving in the city. The one in Barcelona was the last convent in operation on the Peninsula as a result of a decline in the order, starting in the 17th century, when the origin of ergotism began to be linked to mouldy rye. In the Spanish kingdoms, the order had disappeared in 1791, when Pius VI dissolved it at the request of Charles III: the goods and income of the order went to the hospitals, churches and town halls of the places where the foundations lay. Pope Pius VII later integrated the Antonians into the Order of Malta.

Even so, some Antonians remained in the Barcelona convent until 1806.

Portal of the old church of Sant Antoni Abat in Barcelona, after the fire of 1909. (Photo: Àngel Toldrà Viazo).

Lintel of the Hospital Antonià in Barcelona. (Source: Provincial Archive of the Escola Pia de Catalunya).

Curing the sick of Saint Anthony’s fire

When a patient was admitted to one of the hospitals, the Antonians proceeded to carry out various rituals and treatments.

The first thing that was practised was a ritual washing, and then the anointing of the wounds with pork lard. This is probably the scene represented by the altarpiece of the master of Rubió. The schoolboy holds a container of lard, with which the Antonian anoints the wounds of a sick person. This hygienic care acted as an emollient and reduced the risk of superinfection of the necrotic areas. The use of pork lard was linked in such a way to the practices of the Antonians, that soon the pig became an emblematic animal of the saint, which appeared in the iconography, always accompanied by this animal, and here also derives the name of Sant Antoni del Porquet (Saint Anthony of the Piglet) still very much alive in our country.

Detail of the schoolboy with the recipient

In the representations of Saint Anthony, apart from the pig, you can find other attributes allusive to ergotism, such as amputated limbs or flames (in reference to the burning pain caused by the disease) and, above all, the tau or the cane in the shape of a tau, turned into the quintessential symbol of the saint. Another attribute was the bell, which we sometimes find hanging from the staff of the saint, and which was a kind of amulet or charm used to ward off demons.

A fundamental aspect of treatment was the diet. The Antonians gave the sick bread made only from wheat flour. As they fed on wheat bread, which could not be contaminated by the rye parasite, the sick got better. We have known about Saint Anthony’s bread, always marked with the tau symbol, since the 11th century. Even today, it is ritually distributed in many churches on the day of Saint Anthony the Abbot, 17th January.

The sick also received the holy wine, which was kept in the cellars of the hospitals. It was a wine that had been in contact with the saint’s relics on Ascension Day. All Antonian establishments possessed some of these relics. The holy wine had a high alcoholic strength and also contained expensive and exotic added ingredients, such as myrrh, gold or sugar. In addition to being ingested, the wine was used topically for the skin lesions of the sick and must have had a certain antiseptic and epithelialising action.

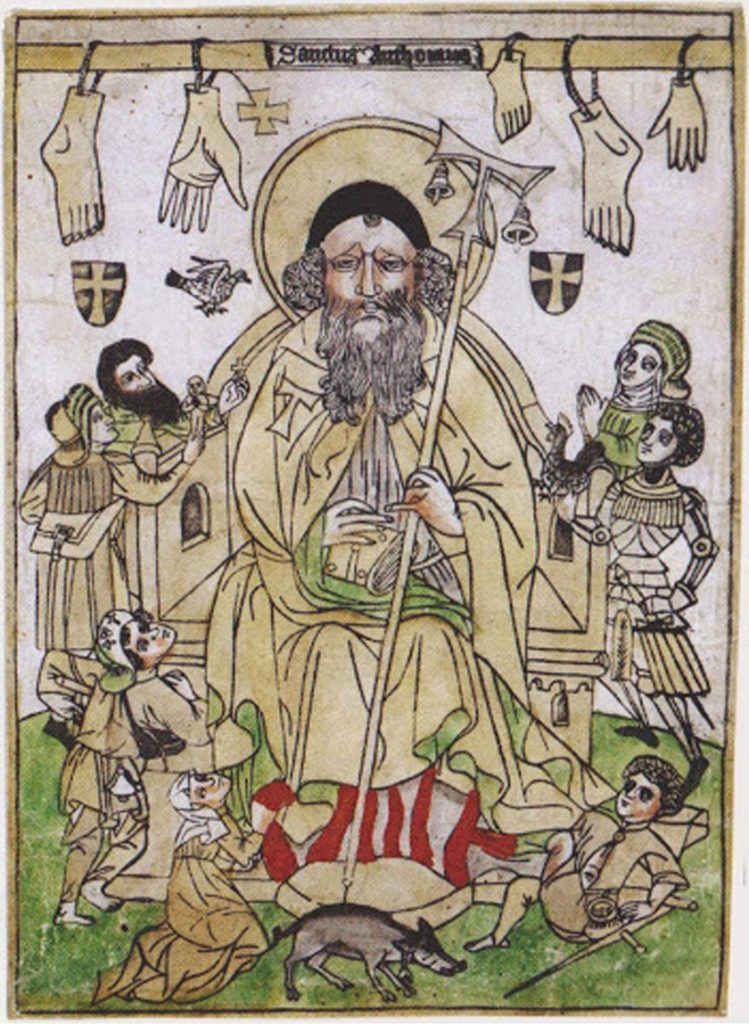

Engraving representing Saint Anthony the Abbot with his attributes: amputated limbs, hanging at the top; ergotism patients mutilated or with crutches; the tau of the staff and of the habit; bells (on the staff or carried by the sick). At the bottom, flames are schematically represented (a reference to the burning pain of the “Saint Anthony’s fire”) and the pig. Some patients bring offerings or votive offerings. German woodcut of the 15th century (Source: “Santos sanadores”. Barcelona: Laboratorios Ciba, 1948).

Finally, the Sant Antoni hospitals had expert surgeons who collaborated there. The Antonian monks, however, could not carry out these interventions directly, since according to the provisions of the Council of Tours (1163), the clergy could not practise medicine and, even less so, surgery and bloody acts. One of the techniques usually used was the sawing method, which was performed with a hot saw on the affected limb. The amputated limbs were desiccated and displayed at the doors of the hospitals, which gave them the name “hospitals of the dismembered”, with which they were often known. The Hospital of the Canons Regular of Saint Anthony of Vienne, well into the 17th century, had an abundant collection of limbs, some bleached and others blackened by necrosis, as a votive offering of the patients who had received assistance Since necrotic limbs – which could also be used by amputated patients – were affected by dry gangrene, they did not rot, and it is for this reason that the beggars, who when they left the hospital were bent on begging, exhibited them to move people and thus get more alms. This can be seen represented in some works of art such as the The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch or in the March of Saint Martin tapestry (16th century) preserved in the Escorial.

Coloured German xylography depicting an amputation by the “sawing” method.

In short, the Saint Anthony altarpiece by the Master of Rubió illustrates an interesting chapter in the history of a disease, ergotism, which wreaked havoc for many centuries, and constitutes a visual, artistic and historical document of role of the Antonians in the treatment of those suffering from intoxication by mouldy rye.

Museu d’Història de la Medicina de Catalunya