Georges Didi-Hubermann

The following text is an excerpt from the opening lecture of the exhibition Uprisings on view at our museum from February 23 until May 21, 2017. The video of the talk (in French with subtitles in English) is now available at the end of this post.

Manel Armengol, Demonstrations of 1 February 1976. Call for: ‘Llibertat, amnistia, estatut d’autonomia’ (Freedom, amnesty, statute of autonomy), 1976 (printing 2003). © Manel Armengol, 2017

There are “righteous furies”, rages which are justified. But how do we discern the rightfulness of a rage, or the act of justice which it claims? How can we justify the uprisings and passionate outbursts which they invariably imply? How do we regulate these rages? What do we mean when we call them legitimate? What are, therefore, grounds for an uprising? In 1795, in Jacquot, Paris, a pamphlet of five pages appeared which was entitled Insurrection en faveur des droits du peuple souverain. It featured the thirty-fifth article of the Declaration of Human and Civil Rights : “When the Government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is for the people, and for each section of the people, the most sacred of their rights and the most necessary of their duties.” Meanwhile, either in 1792 or 1793, the “Enraged Ones” of the French Revolution published their writings, addresses or pamphlets which were, eventually, brought together under the title Notre patience est à bout (Our patience is at an end).

Much later, at the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam in 1907, Emma Goldman arose during the second to last sitting. She proposed that the assembly adopt a text in favour of the droit de révolte (the right to revolt), which her peer Max Baginski had also signed. She read: “The International Anarchist Congress declares itself to be in favour of the right to revolt by the individual as well as by the mass as a whole. (…) Acts of rebellion (…) are the result of the profound impression made upon the individual’s psychology by the awful pressure from our unjust society, (…) (and) can be characterised as the socio-psychological consequences of an intolerable system: and as such, these acts, along with their causes and motives, are more to be understood rather than lauded or condemned.”

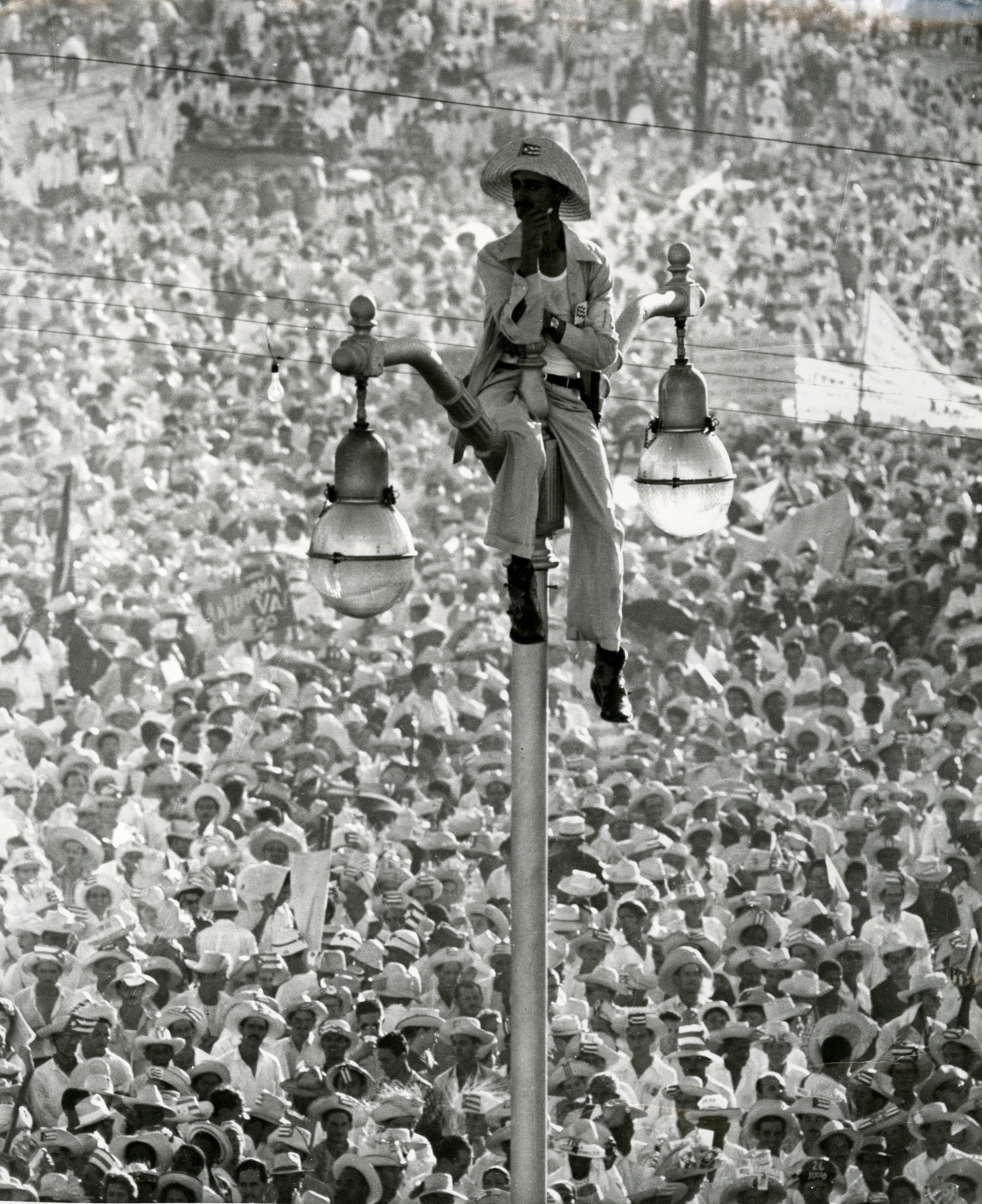

Alberto Korda, El Quixot del fanal, Plaza de la Revolución, L’Havana, Cuba, 1959. © ADAGP, París, 2017

When put to the vote, this declaration was unanimously approved. And yet, the “psychological point of view” which she adopted from the outset never ceased to surprise.

Therefore, there are historically just rages, and just political rages. Let us consider that the Iliad by Homer, the very first political-military chronicle of the West, in the eighth century BC, includes in the very first sentence, the word “rage”: “The rage sing, O goddess, of Achilles, son of Peleus…”

Gilles Caron, Manifestacions anticatòliques a Londonderry, 1969 (còpia moderna, 2016). Fondation Gilles Caron. © Gilles Caron / Fondation Gilles Caron / Gamma Rapho

Peter Sloterdijk, in 2006, in a book entitled Zorn und Zeit (translated into Spanish in 2010: Ira y tiempo. Ensayo psicopolítico (In English: Rage and Time. A psycho-political Investigation) controversially plays with Heidegger’s Sein un Zeit, and proposes a “psycho-political” analysis of the Western civilisation: from Homer to Lenin, therefore, it would be rage that both troubled and moved societies, although the destiny of said rage is only to find its form in a “project”. But does not rage coupled with a project result in vengeance and resentment? It is as though every rage can only find its “political economy” within what Sloterdijk calls the “world bank of rage”, which represents the revolutionary project itself.

The impression that this very general description leaves us with is that rage, scarcely recognised in its historical power, is immediately refuted, as it is propelled backwards towards dark intentions or dark destinies — vengeance, resentment, paranoia — which will fatally channel it. So, where does the anger go?

Psychological tradition would have it that in all cases it goes badly. If there is indeed a philosophical story of the revolution, from Kant to Marx and beyond, there would be uprisings, with their attached “psychological” rages, but a disconnected series of anachronistic crises. It is as if rage itself contributes to carving the difference and, soon, the opposition between revolution and revolt.

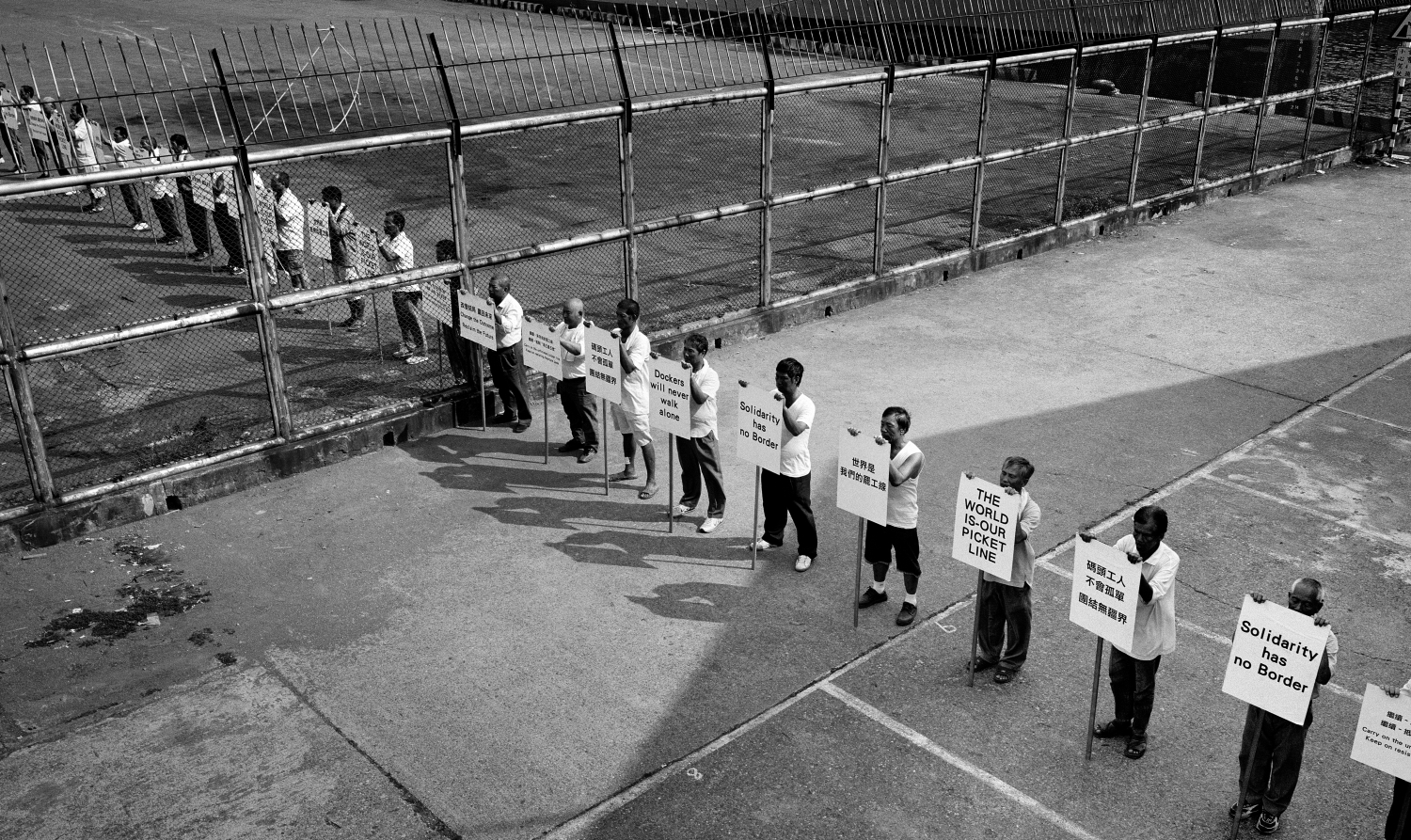

Chieh-Jen Chen, The Itinerary, 2006. Chieh-Jen Chen / Galerie Lily Robert. © Chieh-Jen Chen, courtesy galerie Lily Robert

It would occur to a political anthropologist to think rage at work in the motions of uprising: to consider the intrinsic power of the movement before imagining the project in the order of the power relations or questions of power. Could we not imagine a phenomenology of political rages?

Georges Bataille indicates an excessive movement of which the Hegelian genius, according to him, had allowed us to glimpse: when the thought itself experiences rage without letting go of its consistence and rigour. This is undoubtedly an anarchist’s point of view.

Not by chance, the texts of Mikhail Bakunin waste no time in constructing something like an anthropological equivalence between the act of thinking and that of uprising. The two faculties, both precious and concurrent, granted to the human species are therefore the faculty of thought and the faculty, the need to revolt. Bakunin concluded that, in general, revolt is nothing but another side, negatively expressed, of what is positively identified by the word “pleasure”.

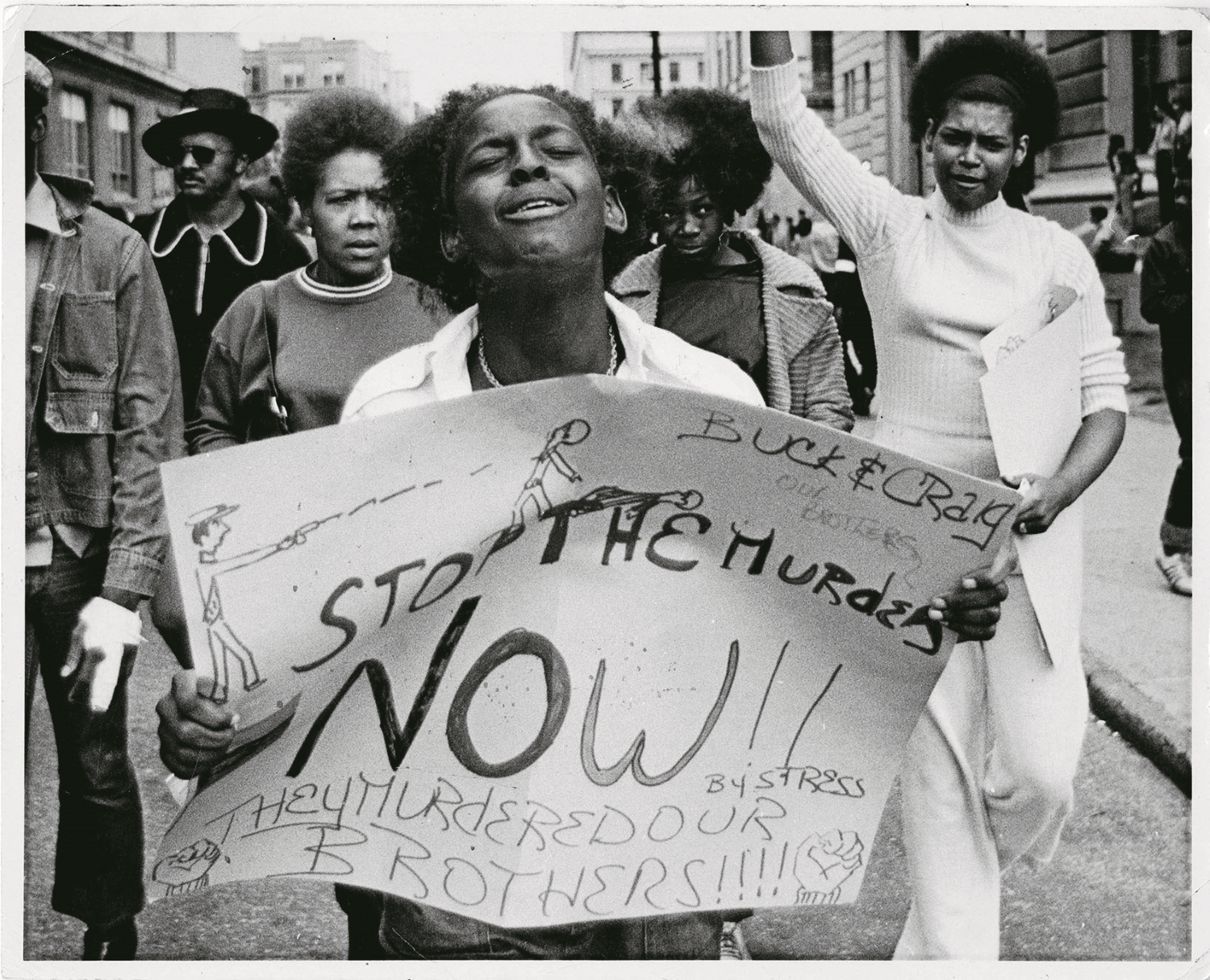

Ken Hamblin, Beaubien Street, 1971. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan, Estats Units

In 1871, Jules Vallès in turn would describe the Paris Commune from a point of view which was, amongst other things, like a mad fête. A way of saying that, in every uprising, rage itself is at the heart of the party, lest we forget that there are also piacular parties (made with collective tears), funereal parties, military parties, wild parties, etc. The festive image of uprisings belongs undoubtedly to mythology which is adopted, at the time or afterwards, by the participants in every revolt.

Therefore, festivity is intrinsically powerful. It is for this reason that Dionysus is its divine protector. It transforms rage into effusive power, even into the power of happiness. It transforms the gesture of fear or aggression into choreographic power. During periods of festivity, which appear timeless, rage become joy and violence a parody. However, states Yves-Marie Bercé, it remains indisputable “that festivities can be dangerous”, in the sense of the most trivial or immediate danger to the people. Bercé also describes how festivities sooner or later turn the signs of power upside down. Waiting to turn power itself on its head.

There is perhaps nothing better than traditional festivities, accepted by everybody, therefore permitted by the government, for expressing desires, even the catchphrases of an uprising. During the two centuries prior to the French Revolution, the political use of festivities went in two opposite directions: to establish or to undermine the existing power.

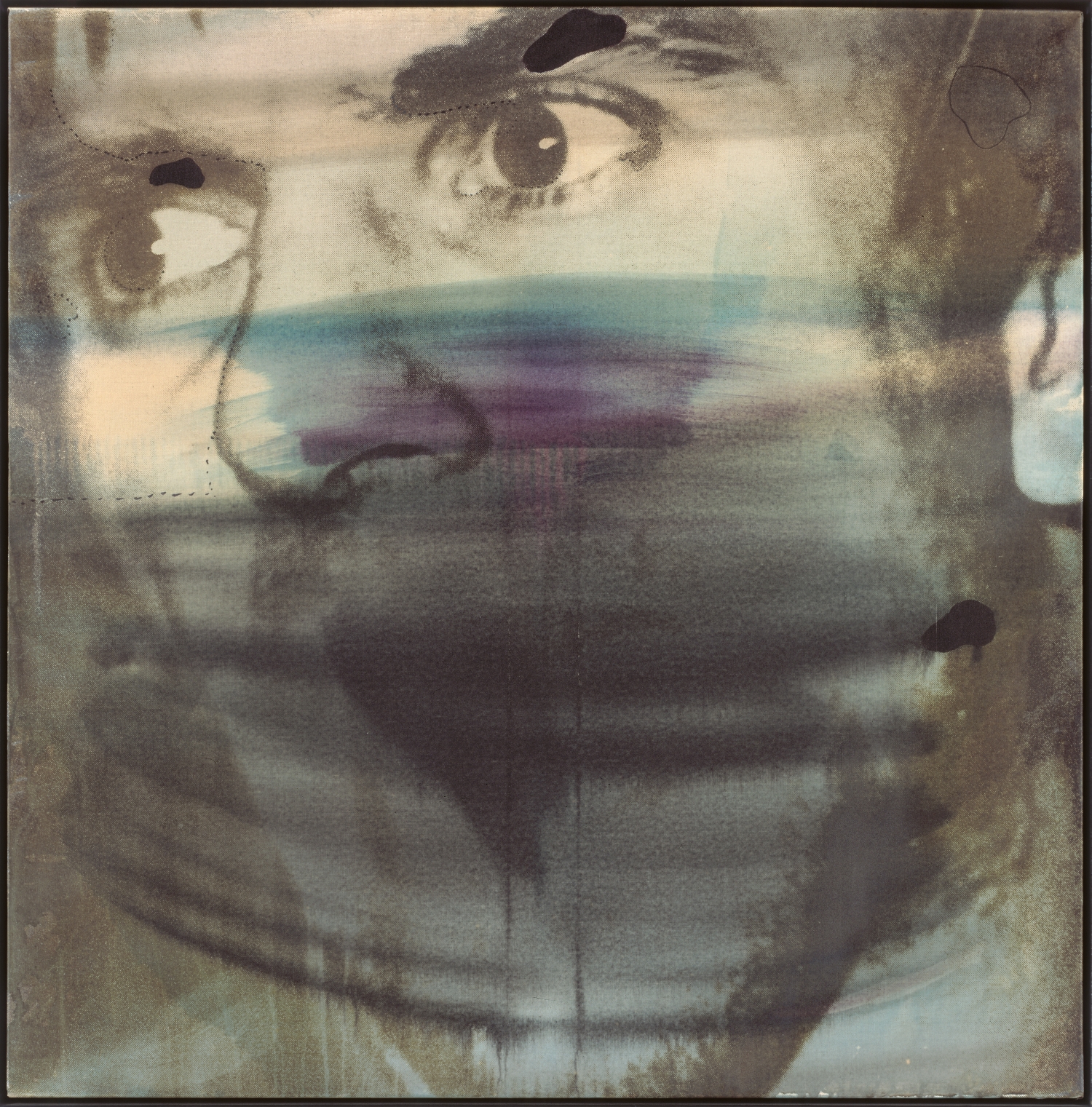

Wolf Vostell, Dutschke, 1968. Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, © Wolf Vostell, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2017

And in this manner, festivities create active violence, by a reciprocal motion to the grief experienced by the violence suffered. But violence acts in all directions: it is neither a value, nor a non-value in itself.

In his book Révoltes et révolutions dans l’Europe moderne, Yves-Marie Bercé details enough cases for us to understand the complexity of the future towards which every revolt is likely to branch. A revolt rises: it shoots up, it surges at first. It is an extraordinary occurrence, unpredictable. But afterwards? After, it may disperse from itself, die away like the cinders of a firework. Or it may be crushed by the authority that it had all too spontaneously contested. In many cases, it ends up being channelled, in other words it is contained, lead astray, halted in its own spurt. When the revolt becomes organised or ordered, this often means that it is subjected to devices and often ends with the subsequent submission to a power, whatever that power may be. Or it gives in to being seduced, steered towards an objective which was not its starting point.

Are there not other destinies for the anger of nations than submission on one side and resentment on the other? It is true that a book like that of Barrington Moore on Les Origines sociales de la dictature et de la démocratie incites the thought that revolts have indiscriminately lead to both the worst and the best.

Maria Kourkouta, Idomeni, March 14, 2016. Greek Macedonian Border, 2016. Producció Jeu de Paume, París. © Maria Kourkouta.

This serves, in any case, to warn us that the words “uprising”, “insurrection” or “revolt” are unable in any way to provide the keys — such as the magic words — to everything concerning desires of emancipation and, in general, to the constitution of the political field. We still have a long way to go (modesty will therefore be necessary). So, where does the anger go? It’s a question that doesn’t unilaterally depend on the strength with which its torrent gushes. It is a dialectical question, or one which calls for a dialectical answer. Bertolt Brecht gives us an insight which is both very simple and very subtle as, in his Journal de travail dated the 28th of June, 1942, he reflects upon the paradox that “hatred is not especially necessary for modern war”. So where is the anger in warlike totalitarianism? “Fascism, responds Brecht, is a government system capable of enslaving a population to such a point that they can be used to enslave others.”

And don’t tell me that this only refers to the past.

Georges Didi-Hubermann

Curator of the exhibit Uprisings

Related links

Où va donc la colère ?, Georges Didi-Huberman (Le Monde diplomatique)

Uprisings. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona. Exhibition curated by Georges Didi-Huberman, 24/02/2017-21/05/2017

Soulèvements. Jeu de Paume, París. Exposició comissariada per Georges Didi-Huberman, del 8/10/2016 al 15/01/2017

Interview to G. Didi-Huberman, Radio Web Macba, 2015, audio 21 min.