Albert Estrada-Rius

Everything that has to do with collectors and the formation of collections is generating more and more interest in our home. We have an excellent example in the project Repertoire of Collections and Collectors of Art and Archeology led by academics Bonaventura Bassegoda and Francesc Fontbona from the Institut d’Estudis Catalans. This project enables, among other goals, a rigorous approach to the creators of many of the collections held by the Museu Nacional. Let’s not forget that the Museum is, after all, a collection of collections and behind each of them is a life story that deserves to be remembered and disseminated. In this post we will take a stop at one very recent and unique example.

Museums, like all institutions, are subject to the changing demands and needs of the society that sustains them. The functions that have been asked of them have changed over time around the essential premise of conserving heritage assets, cataloguing them after studying them, and making them available to the public and scholars. Each of these basic missions has been developed in a process that continues today. Our Museu Nacional provides us with many testimonies when adding new pieces to the collections and is aware that it not only enriches the public artistic heritage and fulfils an increasingly broad social goal, but also assumes an intangible heritage that is intimate, personal and inherent in the objects acquired.

A complete series of 20 German banknotes

Prussian Province of Berlin , 50 pfennige, 1921

More than a year ago now, the Museum received a complete series of 20 German banknotes as a donation to the collections of the Numismatic Cabinet of Catalonia, of 50 pfennige, issued in 1921 during the time of the Weimar Republic. It should be noted that after the end of the First World War (1914-1918) there was a lack of metal and, therefore, the values had to be made on paper as a kind of emergency or necessity currency that numismatics called obsidional money. Despite the difficult economic circumstances, which in the following months would lead to an inflationary spiral in which the issuance of banknotes with millions of figures would be the protagonists, the design of these banknotes was very carefully done.

The motifs that adorn the back of each banknote are historicist views, in the manner of old engravings, of each of the districts that in 1920 were integrated into what was agreed to be called the Greater Berlin Act. It is for this reason that the complete series is often called the eloquent tour of Greater Berlin because, in fact, it allows you to enjoy a bucolic tour of the twenty ancient towns in the palm of your hand. It is a practical and efficient way to use small notes that pass through the hands of all citizens as an instrument of propaganda and commemoration just one year after the approval of the law on urban aggregation, but also a pedagogical and informative means of popularising the names of the new districts of the capital among its inhabitants. The banknotes were also numbered on the back, which made their ordering and collection much easier, as if they were trading cards. The front of the note, with the face value, is unique to all banknotes and shows a version of the heraldic figure of the rampant bear that to this day identifies Berlin.

The fall of the Second German Empire after the abdication of the Kaiser, the signing of the armistice, and the failed Spartacist uprising opened the door to the so-called Weimar Republic that would last until its suppresion by the Nazi regime. It was certainly an age of blatant contradictions. The Greater Berlin Act of 1st October 1920 would turn the capital of Germany into the largest city in Europe. In this way, fourteen towns around the old capital would be integrated as districts of a single large municipality that grew to twenty. In later years the capital completed its total modernisation, based on this broad territorial base, with the creation of the first motorway in the world in 1921, the inauguration of the modern Tempelhof Airport in 1923 or the construction of the radio tower or Funkturm in 1926. This was a period in which Berlin also became one of the most brilliant European cultural metropolises of the 1920s, despite the economic hardships, territorial wounds and national humiliations after the war.

The history of Adolf Linhard, the collector of banknotes

The donation of the complete series of banknotes has an obvious numismatic value to which must be added an emotional life and family story that we now share with the complicity of the generous donor and which must be preserved as an added value to the collection. Indeed, the donation was offered by the cosmopolitan Barcelonan José Linhard, doctor of sociology from the Free University of Berlin and Barcelona founder of the well-known Tertúlia Migdia, who kept them as a memory of his father, Adolf Linhard (1902-1954).

The latter, born in the lands of the old Danubian monarchy of Austria-Hungary, settled in Berlin in a prosperous position and there, like other Berliners, collected them at the time they were issued. We deduce this because the series of banknotes is complete and composed of new uncirculated notes. He also kept them together and accompanied him throughout his life after leaving Germany in April 1933 on witnessing the rise to power of Adolf Hitler. Hitler, as is well known, had unexpectedly managed to lead a coalition of conservative forces after the election and managed to receive the nomination from President Paul von Hindenburg to be Chancellor of the Reich in January 1933.

Adolf Linhard feared the worst. Not in vain, he had read the MeinKampf (1925-1926) and assumed what the Hitler government and the Nazi party would mean for Weimar Germany with its anti-Semitic and pan-Germanist proclamations and programmes. Germany and all of Europe had not yet been able, or wanted, to assume that they were in grave danger but our protagonist saw it very clearly.

Adolf Linhard hurriedly left Berlin as well as the position, safety and wellbeing he enjoyed there, to get just to Barcelona where he didn’t have any contacts. In the city of Barcelona, he waited for his wife to arrive with the aim of continuing his journey by sea, whenever possible, to the United States. The outbreak of Spanish Civil War on 18th July, 1936 he completely frustrated this project and forced them to remain stateless in the city. The situation was further aggravated after the end of the Civil War with the triumph of the national side, which, let us not forget, at that time fraternised with the Axis forces which had contributed so much to their victory. Despite the initial difficulties, the family eventually settled permanently in the city and, after the end of the Second World War and the nightmare of Nazism, they recovered their passports as fully-fledged German citizens, although they did not return.

The donation of the banknotes by José Linhard

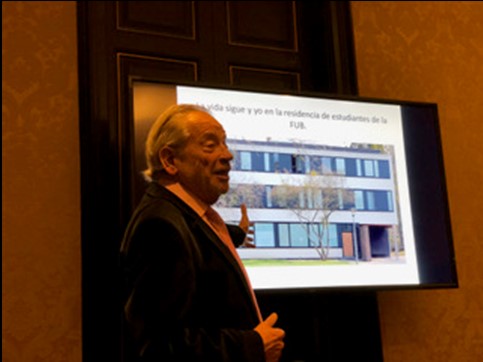

In May 1939, the generous donor of this series was born in Barcelona with both numismatic and human interest. Once the family memory was recovered, he did however return to Germany in 1956 in search of his origins and remained there for more than thirty years in which, from the protocol office of the Western Sector, he was a direct witness to some of the historical episodes in the recent history of the city such as the raising of the wall from 13th August, 1961 or the visit of President Kennedy on 23rd June, 1963.

José Linhard in Berlin in the 1950s while working in the city’s protocol office

But that, as they say, is another story that we hope to be able to read soon in the memoirs he is writing. For the time being, we are left with the intimate story that the series of banknotes holds of the tour of Greater Berlin that now, as everyone’s heritage, remains in the Museu Nacional as a sign of reconciliation on the centenary of their issuance.

Gabinet Numismàtic de Catalunya