Francesc Quílez

The artist’s workshop: a multi-faceted space

Ending this digression and getting back to the connecting thread of my discourse, I wish to demonstrate how this phenomenon of versatility allows me to make different approaches, and to take a very detailed look at the various facets presented by the motif to which I am referring. Really, though, the existence of a great variety of types, and the limits, or the dividing lines, that ought to separate them, are characterized by their permeability, and they crystallize in the appearance of an eclectic, hybrid workshop model.

Concerning the theme of workshops, and their owners, the artists, my interest is focused on the existence of a very large group of productions in a time span dating from the early nineteenth century to the 1930s. The virtual study shows us the importance, throughout this period, of the ecosystem of artistic production.

The focus on the artist v. the focus on the creative surroundings

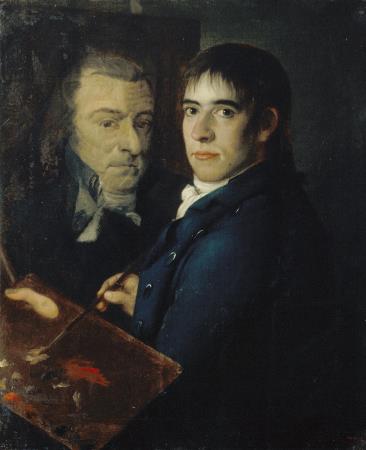

From beginnings still governed by the persistence of the inertia of the eighteenth century and the influence of academic models, in which the artist is the protagonist, captured while adopting a serious, self-important, fake pose, the iconography evolves towards a gradual interest in the natural habitat in which he works. To use a photographic simile, let us say that the painters widen the lens and show us a broader view, in which the interest is no longer limited to just their own face, but it broadens the range of their interests and takes the necessary distance and perspective to also include their creative surroundings.

In reality, both approaches complement one another. In both cases, the painter/author writes his pictorial autobiography, and in this self-referential view the protagonist of the story is as important as the surroundings that help him to assert himself, to boost his self-esteem, and this gives him a certain social status.

The artist’s workshop, or atelier, as a sign of distinction

The notable presence of the workshop emerged from the 1870s onwards, the moment when it ceased to be one-dimensional, a space used to accommodate creative work, especially that associated with doing physical tasks, a sort of place with connotations of prosaic and functional implications, and became a place of public projection: a sign of distinction, a material indicator of the social status acquired by the artist. In short, a display case in which to exhibit himself.

In this respect, the appearance of studio-houses, despite the existence of important historical precedents – think for example of the house where the painter Rubens lived in the city of Antwerp – that fulfil the dual function of a place in which to live and to work, constitutes a model, originating in France, that spread very rapidly and very successfully all over Europe from the 1870s onwards. The atelier is configured as a hybrid type of workshop that demonstrates the artist’s eager wish to imitate and see himself mirrored in the bourgeois system of values. The ostentation, the sumptuousness, the large size, the luxury, the wealth, and above all the ability to show it off, to make this idealized space visible, become aspects that are sublimated by proprietors aspiring to satisfy the idea of comfort, to achieve high purchasing power and to occupy the same place on the social scale as the bourgeoisie.

In line with this model of recognition and social triumph, many ateliers took the form of mausoleums, of large mansions, that oscillated between eccentric chambers of wonders and the reflection of the ideas of the museums of the Enlightenment. In the case of pictorial representations, or photographic images, one clearly sees how these references culminated in the appearance of a sub-genre, the collector’s atelier, turned into a sanctuary devoted to fetishism and the veneration of the patrimonial memory. On many occasions the urge to collect, having become a form of cultural behaviour in that period, resulted in disorderly, unsystematic accumulation, not corresponding to any criteria of erudite knowledge, which never got beyond a leaning towards simple amateurism. The phenomenon of horror vacui was quite common and often generated images of cluttered spaces packed with a jumble of all kinds of objects, with no wish to construct a rigorous historical narrative. Notwithstanding that, we also find many examples in which there is a tendency to monothematic specialization that generally depends on which genre the artist developed: orientalism, historicism, genre painting, and so on.

Related links

Scenes of creation: artists’ workshops / 1

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats