Alícia Cornet

Joan Martí, Portrait of a newborn baby, circa 1860, detail

Most of us associate post-mortem photography with a custom belonging to other cultures, other countries. We see it as a distant practice, which was performed beyond our frontiers. Nothing could be further from the truth. Photographers here took this kind of portrait photograph too. It is true that the photography of the deceased originated in Victorian England, but this practice spread all over Europe and America during the nineteenth century. In Barcelona, the most important photographers of the time, such as Napoleon, Rafael Areñas, Antoni Esplugas, Manuel Moliné, Rafael Albareda and Joan Martí Centellas took post-mortem photographs.

I wish to talk about this practice with a primary objective: to make readers stop seeing photographs of dead people as the result of a morbid, macabre act, and see them for what they really were: an act of love and affection.

Federico de Madrazo, Portrait of the Prince of Asturias. Palacio Real de Madrid

The reason for post-mortem portraits

It is now difficult for us to understand the reasons why someone might ask for a portrait of a dead relative to be taken, and why they would put it in their bedroom, or in a photograph album next to others. Nowadays it would be unthinkable to find, in our albums, the photo of a deceased relative next to our most important ones, those of weddings, the births of children and anniversaries. What led people to demand this kind of picture in the nineteenth century? To understand, we will have to go back in time.

In the nineteenth century, death was not a taboo subject, as it may be now, but a far more visible and familiar matter. Remember that the infant mortality rate was very high and life expectancy was much shorter. People died and their family and friends kept vigil over them at home – funeral parlours did not exist; the first funeral parlour in Spain opened in 1975, in Irache, Pamplona – and once they had been buried there was nothing to physically remember them by. With the passage of time, the loved one’s face was forgotten and, precisely for this reason, so as not to forget, the post-mortem portrait came into being.

Josep Piquer, Dead infante, 1855. Museo del Romanticismo de Madrid

It is a fact that the fear of forgetting and making portraits of the deceased is not something exclusive to the nineteenth century. Mortuary depictions in sculpture and painting have existed throughout history, but it was in that century when a series of important transformations took place concerning the concept of the family, the appreciation of childhood and the treatment of death, which led to the proliferation of this kind of image. It was also in the nineteenth century when, as a consequence of the change in the way of dealing with death and funeral rites, images of dead people were given pride of place in the bedrooms of people’s homes and ceased to be displayed exclusively inside churches and cemeteries, as had previously been the case.

The Spanish royal family contributed to the spread of this kind of image by ordering portraits of their dead children. On 12 January 1850, Isabella II gave birth to a stillborn child, which had been asphyxiated. Because of this, the royal family dispensed with protocol and openly displayed their feelings. They commissioned Federico de Madrazo to paint two portraits of the dead child. Four years later, the infanta Maria Cristina died at just three days old. The queen and her husband, Francesc d’Assís, commissioned the sculptor Josep Piquer to make a wax death mask of the girl, which years later he used to make two sculptures of the infanta. Madrazo also used it, to paint two portraits.

Antoni Caba, The Child Josep Maria Brusi on His Deathbed, 1882

The museum conserves a large number of portraits of the dead, for example The Infant Josep Maria Brusi on his Deathbed, painted by Antoni Caba in 1882, The Dead Miss Riquer, made by Alexandre de Riquer Inglada in 1887, and the death masks made by the sculptor Jeroni Suñol of the painter Marià Fortuny, among others.

The best known is the portrait of Miss Del Castillo on her Deathbed, painted by Marià Fortuny in about 1871. She was the daughter of the owner of the Los Siete Suelos inn in Granada, where Fortuny and his family took lodgings for part of their visit to the city. The owner had no portraits of his daughter made during her lifetime and asked the artist to make a pencil sketch of her. The result, however, was an oil painting of the young woman in her coffin.

Marià Fortuny, Miss Del Castillo on her Deathbed, Granada, 1871

Until the second half of the nineteenth century, having a portrait of oneself made – sculptural, pictorial or photographic – was expensive and, therefore, limited to a well-heeled clientele. The high price was one of the reasons why the majority of families had no pictures taken of the relative when they were alive. The post-mortem portrait was the only picture the family would keep to remember them by. We must also remember that many of those conserved are of children, something that makes the commissioning of this kind of picture even more understandable. To have one gave parents consolation and helped them to mourn, as we may read in an article published in the magazine La Fotografia in December 1904: “The portrait of the dead child is the only memento that cures the grief of the parents who lost him or her; thanks to it, they have the feeling that they can still see them: the portrait of the object of our love sometimes receives as many kisses as our own beloved.” Or in another article entitled “Conveniencia de tener retratada á toda la família” (The advisability of having all the family photographed), published in the same issue of the magazine, where it talked about the grief of a banker with an immense fortune upon realizing that he had no pictures of his 15-year-old daughter who had just passed away.

Photographing the dead: three different ways of portraying them

The first photographic portraits of dead people appeared with the Daguerreotype, but the high cost meant that only a wealthy minority could have portraits taken. With the innovations introduced in the photographic process during the 1850s – wet collodion, calling card size and albumen prints – the costs of the photographic portrait were reduced considerably and demand for them increased in general. The production of post-mortem photographs also increased, and it became a habitual occupation of most photographic studios in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Portrait of dead baby, Moliné i Albareda Studio, one of the most prestigious studios for the quality of their portraits. Private collection

The portrait of a dead person was more expensive than an ordinary portrait and it represented a financial sacrifice for some families. The photographer had to go with all his equipment to the home of the deceased and resolve the problems of light and space that awaited him there. Moreover, although the family cleaned and dressed the deceased, it was the photographer’s job to apply make-up and prepare them to be photographed. And this, in many cases, was a complex unpleasant task, especially when the assignment was to photograph the deceased as if they were alive. Various contemporary accounts talk about it. J. F. Vázquez mentions two representative ones.

- the one written by A. A. Eugène Disdéri in 1855: “I have made a large number of post-mortem portraits, but in all honesty I must say that I do not do it without feeling repugnance.”

- that by the French photographer Nadar: “If there is one arduous task in professional photography, it is the forced submission to these funerary calls.”

For a time, the deceased could be taken to the photographer’s studio, especially if it was a child, but it was more usual for the photographer to go to their home. Even so, in the early years of the twentieth century a law was passed that, for health reasons, prohibited taking the cadaver to the studio, whatever the age.

Broadly speaking, we find three types of post-mortem portraits according to the way in which the deceased was portrayed:

As if they were alive, with eyes open and accompanied by their relatives. In this first type, predominantly from the 1840s and 1850s, the deceased was usually placed in the centre of the composition, surrounded by family or friends. These would be the most complicated to take for the photographer, who had to keep the cadaver standing up or sitting down with the aid of specific implements, and with eyes open or for it to seem that way, painting them onto the eyelids in the photograph. Retouching the print by hand helped them, in some cases, to achieve the desired effect.

Cantó y Cía., Family portrait, undated

Pretending that they were asleep. This was the gentlest type and the most commonly chosen to photograph infants and babies, which photographers normally placed on a sofa or in their parents’ arms. It was the predominant type of picture from the 1860s to the 1880s, and of which we have most examples.

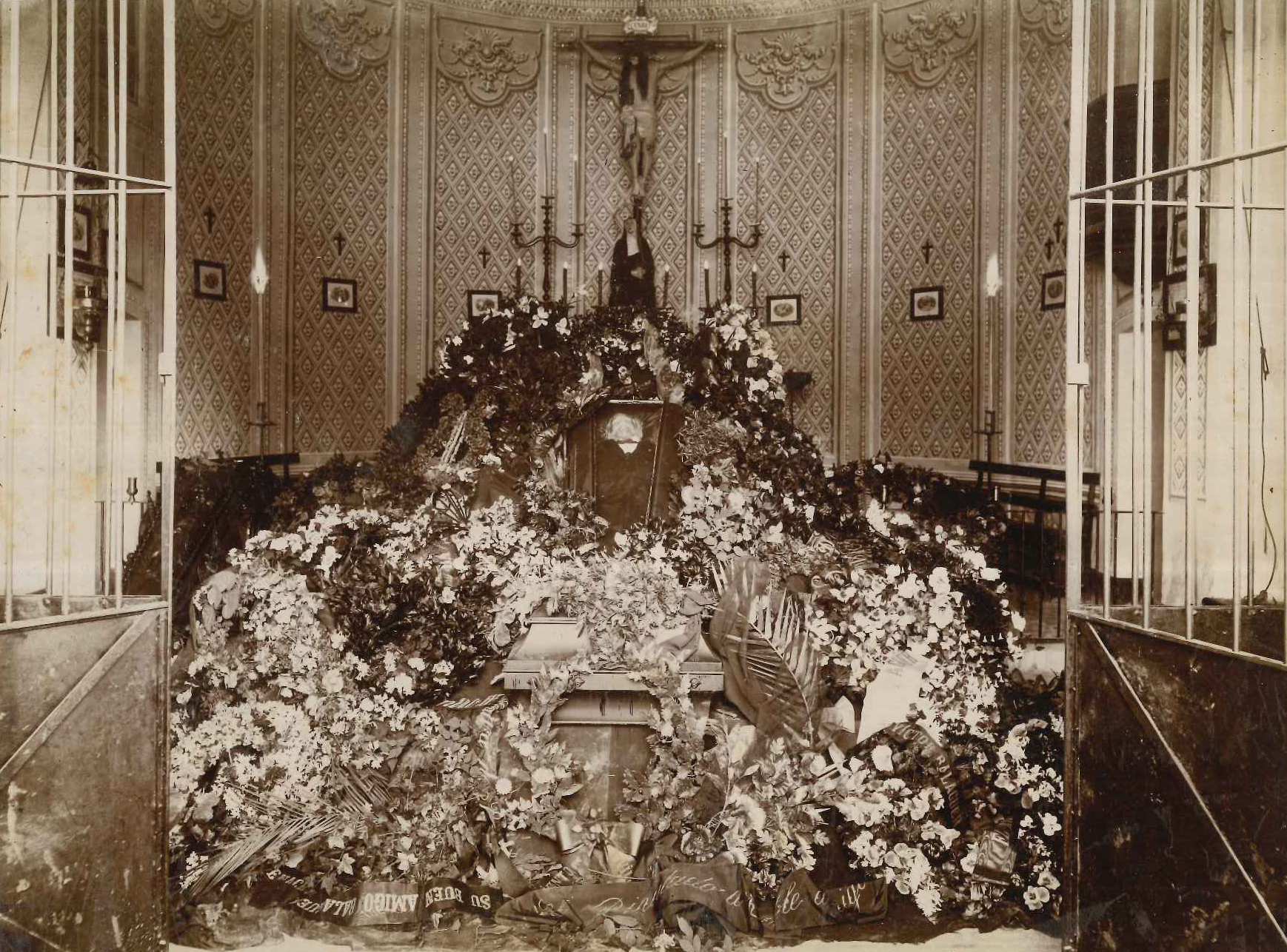

Lying dead in bed, without hiding the state of the subject. This type is the most popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and, unlike the previous two, it signified a clear acceptance of death. In many of these cases, flowers were placed to accompany the deceased, as we can see in this portrait of the son of the photographer Rafael Areñas Tona and Margarita Quintana, who died a few days after he was born.

Post-mortem portrait of Rafael Areñas Quintana, Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

Towards the end of the century, the bed was in many cases replaced by the coffin, as we see in the photograph of the writer Víctor Balaguer, from 1901, which is conserved in the museum’s archive.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, post-mortem photographs were still being taken, but the First World War contributed to reducing production. Wars in general led to a new change in the way of dealing with death and in funeral rites. Photojournalism spread very grim images of wars and society wanted to distance itself from the horrors experienced and from everything to do with death.

Nowadays, as we live in the world of the image post-mortem photography would make no sense. We have multiple photographs and videos to enable us to remember our loved ones when they are gone. But there is one case in which the Victorian tradition would make sense: perinatal loss. When a child is stillborn or dies soon after birth, the parents have no photographs to enable them to remember it physically and to help them to mourn. For the purpose of comforting these families, various NGOs and websites have been created presenting post-mortem photography projects.

In the USA, since 2005 the NGO Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep has been organizing free photographic sessions in which the parents pose with their dead babies. The service it performs has been so well received by families that the NGO is already present in over 40 countries around the world and is working with more than 1,700 volunteer photographers.

In Barcelona, the photographer and psychologist Norma Grau has created the StillBirth project, devoted to families that have suffered the loss of a child. Through her photographs, Grau accompanies them in their grief. The great consolation the images provide for parents can clearly be seen from the long waiting list the photographer has.

Almost two centuries have passed since the first post-mortem photographs, but, as we can see, the reasons that led our forebears to commission them in the nineteenth century is essentially the same as in the twenty-first century: the fear of forgetting.

Recommended links

Deceased young girl, V&A Museum

Death and the Daguerreotype: The Strange and Unsettling World of Victorian Photography, Creators, 2016

Documentació