Albert Estrada-Rius

Why am I writing this post? The reason is to complement, from a personal point of view, the exhibition that can be visited until 1 March in the vestibule of the Joaquim Folch i Torras Library about the figure of Francesc Paradaltas i Pintó (1808-1887). The idea is to return to some of this blog’s original objectives. That is, not to focus so much on presenting content produced by the museum, but rather, in an exercise of transparency, to share a singular look at what lies behind the research and to one’s personal experience of preparing the activity or project. Therefore, what better than to share the series of circumstances that leads one to embark upon the construction of a biography of a virtually forgotten man from Barcelona?

View of the free exhibition dedicated to Francesc Paradaltas in the vestibule of the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library, in the Museu Nacional (photo by the author).

The basis of what we might formally call the “Paradaltas project”is a small collection of documents conserved in the Museum. It is well known that museums, archives and libraries are an inexhaustible source of information and inspiration for researchers and scholars and for conservators and archivists. The latter two have the duty to catalogue the collections in their care and to thus facilitate their dissemination and study. After safeguarding and cataloguing the heritage, the ultimate aim is always to share it and make it available to the public.

In this case it is a collection of personal documents. A few pieces of the jigsaw puzzle of our protagonist’s life. Among the documents, we find, for example, an appointment as the assayer of the Barcelona mint, a passport to go from Madrid to Segovia, some accounting notes and an enigmatic handwritten text about the Spanish monetary reform.

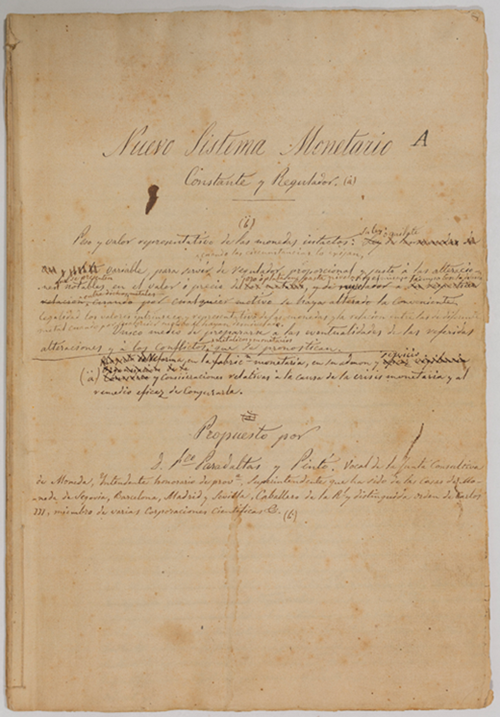

Front page of the unpublished handwritten text by Francesc Paradaltas, signed in Seville in 1864, in which he returns to the subject of monetary reform.

Behind the few, at first sight, dry documents there are, however, some unique beautiful data that open a window onto the life of a flesh and blood figure, until recently virtually forgotten in the encyclopaedias. So, who was Francesc Paradaltas? For some numismatists, a surname recalled only by the initial “P” struck on some Barcelona coin issues.

Isabella II. 1 peseta of Barcelona, 1836. On the front, the initials of the two assayers, the guarantors of the issue. The “P” corresponds to Francesc Paradaltas.

Only the numismatists Anna M. Balaguer and Miquel de Crusafont had had the good grace to mention him in a brief paper at the National Numismatic Conference held in Saragossa in 2002. In this pioneering work they shed light on this figure who played an important role at the Barcelona mint and to whom we owe a couple of published books that are also conserved in the Museum library. It is a fact that Paradaltas himself made it his business to widely disseminate his Tratado de monedas (Treatise on Coinage, 1847), and it is therefore on record that he had several copies sent to the Congreso de los Diputados, the lower house of the Spanish Parliament in Madrid, as well as one dedicated to the Minister of Finance and, among many other contemporary figures, to Queen Isabella II herself.

For some, he was merely a minor figure on the stage of the zarzuela of Isabelline Spain. That may be so, but these days we demand that the story be written by the whole of the citizenry, and that of the public administration, beyond the major figures of ministers and heads of government, is sustained in time by these “minor” figures who, when they are studied, prove not to be so minor. In short, studying these unknown profiles is also a historiographical decision to which I have committed myself.

Paradaltas’s two main published works. Memoria acerca de la antigüedad y utilidad de la casa de moneda de Barcelona, Barcelona, 1845, and Tratado de monedas y proyectos para su reforma, Barcelona, 1847.

Having weighed up the importance of the man and the little that was known of him, it was clearly necessary to shine a light on such a singular, hidden museum collection. No sooner said than done, the documents were the subject of two initiatives in the framework of the 17th Hispanic Monetary HistoryCourse promoted by the Numismatic Cabinet of Catalonia in 2013 on the subject of The Industrial Revolution and Coinage Production: The Barcelona Mint and its Context. First, an inventory and a description in the publication of the aforementioned course and in an article with an updated revision of the author’s biographical notes. A necessary step of cataloguing, study and dissemination.

The second step was to search for further information with other sources outside the Museum. The search for descendants and relatives, usually so useful in other biographies, has in this case turned out to be very frustrating. Except for a photograph that was published at the time there seemed to be nothing left in the possession of his descendants who, with the loss of the surname, had also forgotten about him. What a shame! Let us hope that with the exhibition and this post other sources and information in the hands of private individuals might appear! I am sending out a call to all the possible descendants whose surname is Alabau i Solà!

Photograph of Francesc Paradaltas, provided by one of his descendants (Alabau Family Archive).

Very often, in the Museum the task of the conservator ends at this point. Projects have to be concluded and the need to initiate new ones means that promising investigations are cut short once a series of results has been presented to the public. This is not the case here because historical research is often like a viper with a bite that inoculates one withan addiction to discovering the truthand, why not, to assuming a certain feeling of doing historical justice. And this has been the case with the study of the figure of Paradaltas. It is difficult to explain to people who are not well versed in research. A personal bond is established with the subject of the research that goes beyond one’s professional obligations. In short, a personal undertaking is created with the research, such that the investigation does not end and is resumed at the first opportunity.

The figure’s relationship with the Barcelona mint, the start of the excavations in some of the rooms in this establishment and the appearance of new traces in the industrial renovation of the building in 2014-2015, related to Paradaltas’s reforms, once again called for more in-depth research into the figure’s work. In this blog I reported on these new developments associated with our protagonist in two posts about the Barcelona mint.

Two testimonies of industrial archaeology in the Barcelona mint. Archaeological work in the machine room with the bases of the presses and the chimney erected in 1858 (photos Albert Estrada-Rius).

At this point, the search made it necessary to follow the figure’s trail in the newspaper and periodicals library and in the archives of the institutions with which he was associated. This has involved consultations in, among others, the National Historical Archive, the archive of the Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts and that of the Societat Econòmica Barcelonesa d’Amics del País, but also in the Civil Registry, the Archive of the City of Barcelona and the Historical Protocols Archive of Barcelona, in the Municipal Archive of Esplugues, or in those of the French institutions where he studied. In some archives the prospections have been fruitless while in others they have produced results. These are moments of frustration or euphoria in which the involvement of the archive and library staff is essential and this is a good time to thank them for their priceless task of support and guidance. The information piles up and patience and tenacity are two essential companions along with logic and intuition.

Medal no. 1 of the number one academic of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts held by Francesc Paradaltas and award medal of the Barcelona Economic Society of Friends of the Country. Photos by the author of the pieces preserved, respectively, in the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts and in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

There still remained the study of his published works (in 1845 and 1847) and the unpublished one (1864), which are now exhibited in the Museum, and other works that were written in the form of reports and handwritten opinions for internal use in the bodies of which he was a member, both on his own initiative and by order. In the course of research work there are always surprises. On this occasion, the discovery of an announcement in the press with the opening of the public subscription for the 1847 book has clarified the provenance of some decontextualized sheets of coin illustrations in the collections of the Museu Nacional. In the announcement the imminent publication of the well-known work was advertised and a public subscription was opened for the second part, made up of about 50 sheets with illustrations of coins from all over, of which it was claimed that there were already five engraved. The public subscription was a failure and the planned second volume never saw the light of day except for the five sheets that are conserved in the museum and which have now been restored with the rest of Paradaltas’s documents and properly contextualized as galley proofs of the unpublished work.

Sheets identified as being by Francesc Paradaltas. The one on the left is a galley proof of sheet 1 from his 1847 treatise. The one on the right is one of the five unpublished sheets of the plan for 50 copies of the second volume, never published, of the work announced in the press.

In this long, patient itinerary, personal and work-related administrative data were being collected that placed him in a professional career and a family life. His liberal economic and decentralizing ideas also surfaced and also details that shed light on his enterprising and enthusiastic nature. tackling someone’s biography always entails trailing the figure rather obsessively. And not just in the papers conserved in the archives. It also involves focusing on the real scenes of his life and even getting to the place where he was buried. Why? It is a case of putting oneself in the protagonist’s shoes as far as is humanly possible. Any detail could supply a new investigative lead. Historical research is more like detective work than you might think and it ranges from contacting particular individuals who have information, and it is necessary to obtain their permission for the consultation, to visiting the places where he lived and worked. The historian interprets the content of the papers but he also wishes to make the silences meaningful.

A new phase – that of the dissemination of the collections in an exhibition – is thus completed in the life of the Museum and also of the researcher. It is one of the results of the research that I hope may one day culminate with a biography that once and for all rescues Paradaltas from oblivion and gives him his rightful place in the gallery of Catalan entrepreneurs who were the protagonists of the Industrial Revolution in the turbulent years of Isabelline Barcelona.