Martí Casas

Have you ever wondered why we Catalans fem dissabte (clean the house on Saturday)? Or why we eat bunyols (fritters) for Lent? Or why we make slaughtering the pig, an essential source of food in our cuisine, a big public event, but not slaughtering the lamb or the calf, animals that are also part of our traditional gastronomic corpus?

These are some of the examples that the poet and Hebrew scholar Manuel Forcano shared with us last April in the museum’s Gothic Art galleries. He spoke to us about the persistence of the Jewish legacy in Catalonia, despite the fact that the Jews were expelled more than 500 years ago, and he guided us through the evidence of it that has survived in art.

The history of the Jews in Catalonia

According to some sources, the history of the Jews in Catalonia dates back to the first century AD with the arrival of the first communities. Whether it was then or later, what is beyond doubt is that the Jews settled in Catalonia before Catalonia and Catalans existed as such. Their presence was solid and stable. It spread to almost all parts of the country and lasted for practically 1,500 years. It was hardly ever, however, a calm existence: from the moment when Christianity became the hegemonic official religion, the Jews were viewed with profound suspicion. In most periods they were tolerated at best, and even though they were not persecuted they would never be completely accepted, nor would they be allowed to fully integrate in society.

Everything suggests that the first centuries were peaceful, so much so that Judaism gained adepts and generated a considerable number of conversions that annoyed and worried the Catholic Church. The two religions, with an important common root, were not so different then, and changing from one to the other was easier.

To begin with, the arrival of the Visigoths in the fifth century did not affect the Jews because the new invaders were Arians, an eastern Christian denomination. But when they were eventually converted to Roman Catholicism, the Church and the State began a first period of repression and persecution of the Jews, who were saved by the onset of the Moorish invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711.

Detail of James I in the Mural paintings of the Conquest of Majorca, 1285-1290

Living in Catalonia under Muslim rule was one of the happiest times for the Jews. The Arabs respected their faith and allowed them to practise it freely. Later, in Catalonia under the rule of the counts, and during the reign of King James I, the circumstances were also favourable for the Catalan Jews in Christian territory, with the notable presence of many illustrious members at court as advisers in the service of the king.

This period of tolerance, on both sides of the frontier during the Reconquista, encouraged literary and intellectual creativity and made it possible for great figures of Jewish culture to flourish in Catalonia. Forcano mentioned the poet and mathematician from Tortosa Menahem ben Saruq, the author of the first Hebrew dictionary, and the rabbi Shlomo ibn Aderet, the director of the Talmudic academy in Barcelona, who has bequeathed to us more than 3,000 answers to doubts and consultations that were addressed to him by Jews from all over the world.

Despite James I good treatment of the Jews, at the end of his reign not even the king himself was able to prevent the imposition of increasingly coercive measures against the people of David. It was the prelude to the XIV century, the most terrible in the history of Judaism in Catalonia. Even before the beginning of that century, Jews all over the Principality were forced to wear specific clothes or badges to distinguish them from Christians. This mark, either a hooded cloak as in Barcelona, or whatever was decreed in each city, encouraged the stigmatization of the Jews and made their everyday lives enormously difficult.

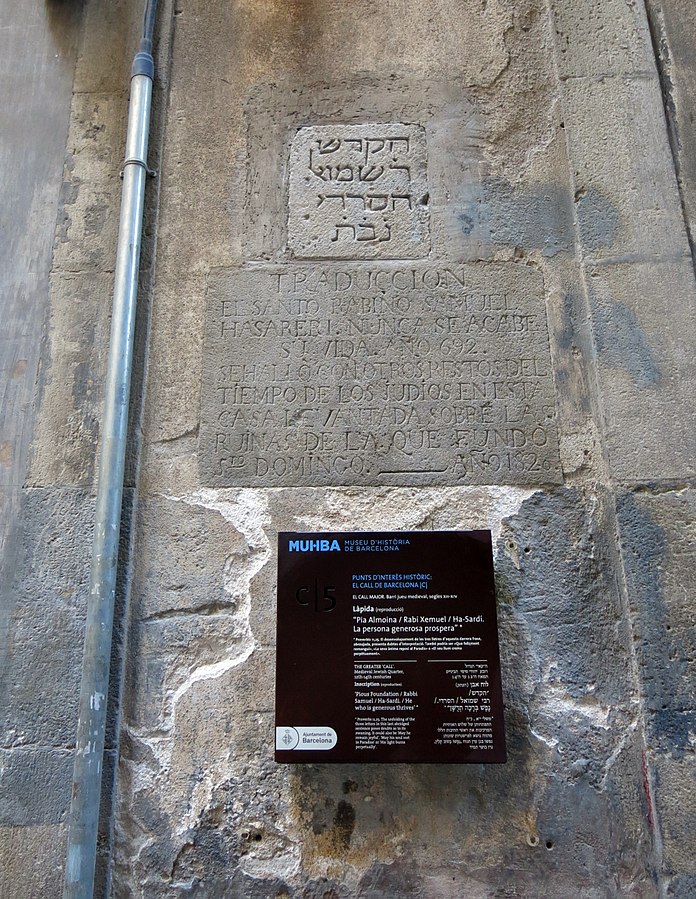

Marlet Street at the junction with Sant Domènec del Call, Barcelona. Font: Wikipedia

Moreover, after decades of economic and social expansion, the XIV century was a time of crisis and disasters, with a series of plagues, epidemics and earthquakes. The Jews were blamed for all these ills and anti-Semitic hatred grew in Christian society, fanned by part of the Church and the orders of preachers. This anti-Semitism came to a head in 1391, with a huge wave of massive attacks in calls (Jewish quarters) all over the kingdom, which, despite the king’s attempts to stop them, seriously and irreversibly decimated the aljames (Jewish communities).

After these attacks, the XV century witnessed the death throes of Catalan Jews. Many Jewish quarters disappeared, and few families remained, because the majority had either died, gone into exile or had converted to Christianity. The decree of expulsion of 1492 was merely the coup de grâce that certified the official end of the Jewish presence in Catalonia. Forced conversions of many of the communities, however, did not reduce the threat of violence towards converted Jews (conversos). Instead of seeing their sacrifice rewarded, they were perpetual suspects that had to be watched over carefully.

The accusation of Jewish practices, formulated maliciously by anyone near them, could bring down the implacable cruelty of the court of the Inquisition on the head of any Christian, converted or not. This was the origin of certain social practices with which the people most likely to be accused of false conversion wished to proclaim publicly that they did not practice the Jewish faith or observe its traditions. This is the reason for cleaning the house ostentatiously and more intensely on a Saturday, the Jewish holy day, so that everyone can clearly see that it is not a holiday. And fritters are eaten for Lent, so that everyone realizes that on the days close to the Jewish Passover nobody is eating unleavened (Azim) bread, as ought to be the case. And a big show is made out of the slaughter of the pig, inviting relatives and neighbours, so that everybody in the locality can see that in this house there is no prohibition to consume pork, as stipulated by Jewish law. And centuries after the official end of Judaism in Catalonia we still preserve and perpetuate traditions born out of the profound fear of being accused of being a Jew.

Jewish women with hood and roll on the head, fragment of the Altarpiece of the Saints John, circa 1435-1445

Graphic evidence in the collection

A walk around the museum’s Gothic Art galleries allows one to see that practically all artworks prior to the expulsion of the Jews were addressed to Christian worshippers. Many therefore offer an especially negative image of the Jews and Judaism, with the wish to “debase” them and show them as a group totally different to Christians, which concentrates and accumulates the worst defects: ugliness, filth, ridiculousness, and so on. In many of these works the Jews appear characterized according to the physical stereotypes that began to spread at that time.

Anonymous, Beam of the Passion, circa 1192-1220

As Forcano noted, this distinctive representation of the Jews was never extended to Jesus, the Apostles, or to any of the holy figures of Christianity, although to all intents and purposes they were all Jews as well. Only the Jews that appear in the Holy Scriptures who did not convert to the new religion were differentiated. Figures who, in many cases, are the main antagonists of Christ, like the priests in the Temple.

This different treatment of the Jews appeared very early in Catalan art. One of the oldest testimonies conserved in the museum is the Beam of the Passion, on which the Jews appear with completely black faces, as if they were Africans, according to an old Byzantine tradition. This peculiar racial code for Jews may well have been in use until the end of the XIII century, as in the paintings of the conquest of Majorca a black figure appears at the top of a tower where a flag with the star of David is hoisted. Although this symbol was not then associated exclusively with the Jewish people, the crucial role that the Jews of Mallorca played in the conquest might reinforce this identification.

Master of the Conquest of Majorca, Mural paintings of the Conquest of Majorca (detail), 1285-1290

The passing, at the end of the XIII century, of the first dispositions in which the Jews were obliged to wear one or more distinctive elements every time they left the Jewish quarter would make racial distinction in art unnecessary: it was enough to show them with the clothes and roundels that they were forced to wear in public places all over Catalonia. In the majority of Gothic panels of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in the museum, the Jews appear dressed in the clothes that were obligatory in the city of Barcelona: the full cloak, which covered the entire body and had a hood. We can see an example of it in the scene of Jesus among the Doctors in the Altarpiece of the Virgin, from Sixena.

Jaume Serra, Altarpiece of the Virgin (detail), circa 1367-1381

Continuing with the visit, the artistic treatment of the Jews in Catalan Gothic art got worse as time passed. In works of the first half of the fourteenth century they are still depicted in a way that we might almost call “neutral”, despite the fact that we find them in scenes highly critical of Jews. It is a fact that they wear the clothes that stigmatized them, particularly the full cloaks, but this is the way that Christians of the time, painters included, were accustomed to seeing them in the street, outside their own quarter. Besides the distinctive element of the clothes, the faces and features of the figures identified as Jews have a treatment and details comparable to those of Christian figures. The Jewish figures that appear in the altarpiece and the altar frontal of the Corpus Christi bear witness to this.

Master of Vallbona de les Monges (Guillem Seguer ?), Altarpiece of the Corpus Christi, circa 1335-1345

Master of Vallbona de les Monges (Guillem Seguer ?), Altar frontal of the Corpus Christi, circa 1335-1345

This apparent equality between Christians and Jews in the depiction of faces changed drastically from the middle of the XIV century onwards. In the works of the Serra brothers, for example, the facial features of those identified as Jews are starting to acquire the stereotyped traits attributed to them: big hooked noses, a prominent chin and long bushy beards. Their facial expression became more disagreeable. There thus began a tendency that was increasingly accentuated and reached almost grotesque extremes.

Jaume Serra, Altarpiece of saint Stephen (detail), circa 1385

By the turn of the century, the faces of Jewish figures were completely caricaturized, with the aim of showing the maximum physical debasement of the community they represented. Forcano mentioned several significant pieces of evidence. One of them is the panel of the Resurrection of Christ from the high altarpiece of Santes Creus, by Guerau Gener and Lluís Borrassà, in which one of the soldiers watching over the tomb of Jesus appears with pig-like features, an unusual but by no means accidental choice if we bear in mind that this is an animal that Jews are forbidden to eat, and that eating pork was one of the social characteristics that most clearly distinguished Christians from Jews.

In the scene of the Kiss of Judas, by the Master of Retascón, the supposedly Semitic physical features of both the famous traitor and the soldiers that arrest Christ can very clearly be seen: an ashen complexion, a large hooked nose, a prominent chin. Our attention is also drawn to the look of profound hatred that the painter has shown in the eyes and the features of all these people. The only thing that slightly excuses the artist is that in this case, curiously, the figure of Jesus also seems to reproduce the physical stereotypes habitually attributed to the Jews.

Besides observing the gradual degradation of the artistic depiction of the Jews, Manuel Forcano also mentioned the harshness of the deeds that are ascribed to them in the scenes in which they appear. The members of the people of David mainly appear, clearly and explicitly, in two types of scenes: theological disputes, which obviously always end with the dialectical victory of the representatives of Christianity, and the Jews’ alleged sacrilege against the Christians’ sacred symbols, chiefly the consecrated host. The prominence of these two themes is significant, because both of them reflect very topical realities in the Middle Ages in Catalonia. In the Crown of Aragon various theological disputes were instigated and several trials are recorded of Jews accused of having profaned Christian symbols. Gothic altarpieces, therefore, simply reflect and echo situations that generated debate and controversy in Christendom at the time.

The theological disputes depicted in the museum’s Gothic altarpieces are not contemporaneous with the works, but they reproduce religious debates that appear narrated chiefly in the New Testament, associated with the life of Jesus or that of Saint Stephen. In the rooms there are several examples. The Young Jesus’ dispute with the Doctors is a scene that usually appears in iconographical cycles of the life of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, and it is well represented in the museum by the Altarpiece of the Virgin from Sixena.

The most common scene is Saint Stephen’s dispute with the Sanhedrin, an episode described extensively in the Acts of the Apostles and which ends with the saint’s martyrdom, since the priests, furious because they cannot defeat him dialectically, order him to be stoned to death. In most of these scenes the Jews appear in very aggressive poses, covering their ears or tearing up the scriptures as a sign of disapproval. In others, as in the panel by Ferrer and Arnau Bassa, we find on the other hand some Jews looking clearly grief-stricken, as if they felt they had been defeated by Stephen’s theological arguments.

Ferrer and Arnau Bassa, Saint Stephen’s Dispute with the Jews, circa 1340-1360

Although they are New Testament episodes, the Christians of the time saw in these scenes a clear reference to the different disputes or controversies that took place in Catalonia in the late Middle Ages, in which the arguments of an important Jewish leader were always contrasted with those of a Jew converted to Christianity. Two stand out especially: the one in Barcelona in 1263, in which the Jews were allowed to speak freely and for many of those present they won the dialectical argument, the reason why the speaker, Nachmanides (Bonastruc ça Porta), had to go into exile. And the one in Tortosa in 1414, far less balanced, which the Jewish rabbis were forced to attend. After 67 sessions, they were made to sign a document in which they acknowledged their mistakes, and in many cases they were forced to convert.

With regard to the depiction of the supposed sacrilege committed by Jews against the sacred elements of the Christians, Manuel Forcano pointed out especially the two panels dedicated to the Corpus Christi attributed to the Master of Vallbona de les Monges. In it we find a series of defilements by Jews of the consecrated host, which according to Christian beliefs became the body of Christ during Mass. In various scenes one sees how a Jewish moneylender acquires a consecrated host from a Christian woman in return for pardoning her debts, and subjects the sacred form to a series of attacks to try to profane it and thus mock Christianity and the dogma of Transubstantiation. Despite being stabbed, stuck on the end of a spear and boiled, the host remains miraculously intact but bleeds profusely, something designed to show that it is the body of Christ.

Guided by Manuel Forcano, we have learned of details and aspects of altarpieces that usually go unnoticed, in a very complete study of the numerous Jewish references conserved in the Gothic works of art exhibited in our Museu Nacional.

Related links

“Adversus iudaeos” paintings in the Gothic art collection, Cèsar Favà

Amics del Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya