Martí Casas

As the Christmas festivities approach, just about everyone at home is clear about which figures can’t be missing in a crib, just as it should be: the Holy Family, the ox and the mule, the three wise men with their pages…and of course we can’t forget the caganer! Taking a look at the collections of Romanesque and Gothic art of the Museu Nacional we can quickly catch the different visions that they had in the medieval period of some of the episodes linked to the Christmas festivities. Do you want to join us?

Serra brothers workshop, Adoration of the Shepherds, circa 1365-1375

Initially, it should be said that in the Middle Ages there were different versions about how the scenes should be represented and the characters related with the birth of Christ. Why? The main reason is that the three most notable episodes of Christianity that are linked to Christmas – the Nativity of Jesus, the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Epiphany or the adoration of the Kings- appear described in a very brief way in only two of the books of the New Testament: the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. In the first, it only says that Jesus was born in Bethlehem and then explains the visit and the adoration of the newborn child by some «Wise men from the Orient» that would have arrived by following a star that showed the way. For his part, Luke very briefly explains the birth of Christ, highlighting the fact that Maria, his mother, «placed him in the dining room as there was no room for them in the inn» of Bethlehem. After that, this book narrates in a more extensive way, the announcement of the angel to the shepherds and their adoration for baby Jesus in the stable.

The brevity in which the official texts of the Church described one of the most important moments of Christianity forced theologians and artists to resort to other sources to know more in detail about how things had really taken place. These other texts are the biblical apocrypha, very old narrations about the life of Jesus and Mary that have never been considered to be official by the Church, but neither have they been prohibited. From among them, the ones that talk of the childhood of Jesus, like the Proto-Evangelium of James or the Gospel of the Pseudo-Matthew, were used in the Middle Ages as a source of Christian iconography and everything it says helps us to understand some of the old representations of the scenes linked to Christmas.

A singular Romanesque Birth of Jesus

Master of Sorpe, Birth from Sorpe, Mid-12th century

To see to what extent the representations of the Birth of Christ have changed since the Middle Ages, it is only necessary to take a look at the singular Nativity scene that we can find in the mural paintings of Saint Peter of Sorpe, a series from the mid 12th century, of which a part is conserved in the Museu Nacional. Here we see the Virgin Mary totally lying down, at the top, while two women wash and purify the baby Jesus, who, despite just having been born, stands up on a bathtub in the shape of a baptismal font. To the left of the group, half erased, we can make out the figure of Saint Joseph, sitting alone at the end of the scene.

So, where does this iconography and these singular characters emerge from? The Nativity of Sorpe is a representation inspired by Byzantine art and based on apocryphal books. According to these books, Mary didn’t give birth in a stable but in a cave, where she entered completely alone, and gave birth without the help of anybody. When Jesus had been born, Joseph entered the cave accompanied by two midwives, called Zelomi and Salomé. The first one was marvelled on contemplating the miraculous birth of the son of a virgin mother, but the second did not believe this prodigy and wanted to make sure by touching the Virgin Mary. According to the Apocrypha, Salomé was punished for this disbelief: by touching Mary’s hand she cured her in the midst of great pain, but as she immediately regretted having doubted, she was able to heal her by taking the child in her arms.

Mosaic of the Nativity of the church of Martorana of Palermo. 12th century. Cappella Palatina. Palazzo Reale di Palermo

What is it that is surprising about the Nativity of Sorpe? First of all, the fact that Mary is lying down. This disposition between lying down and leaning of the Virgin Mary is habitual in the representations of the Birth that we can find in Byzantine art, which show Mary resting exhausted after the childbirth. This is what we see, for example, in the mosaic of the Nativity of the church of Martorana, in Palermo, built in the 12th century by Byzantine masters who expressly went to Sicily. The fact that the Virgin is lying down can also be a reference to the fact of giving birth in an underground cave, which, due to its small size, must have forced her to remain lying down.

The image of the two midwives washing Jesus after birth, which we find both in Sorpe and in most other Byzantine nativity scenes, shouldn’t shock the visitor either. This action is not narrated by the apocryphal gospels, but the bathtub of Jesus already appears from ancient times in Byzantine art, where it eventually became an iconographic theme. It would also become habitual in the eastern world to portray Joseph as an old and angry man, sitting alone in a corner of the scene with an expression on his face between sadness and anger. This image is also born from the apocryphal gospels, who show us Joseph as an elderly and ill-tempered man, displeased by Mary’s pregnancy to the point in which he planned to leave her. Only the appearance of an angel in his dreams would change his mind.

Giotto da Bondone. Nativity scene of the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi. Around 1308-1311. Source: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

The art of the Byzantine Empire took on enormous prestige in the Middle Ages and for this reason its iconographic models were spread throughout Europe for decades. In Italy, for example, some of the scenes of eastern inspiration would remain almost until the Renaissance. This is very well exemplified by the Nativity scene that Giotto and his workshop painted at the beginning of the 14th century in the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, a fresco which follows almost exactly the same model of the Nativity painted in Sorpe two hundred years before. In Catalonia, the influence of Byzantine iconography is especially felt during the Romanesque period, but some of the characters and themes which originated in the Eastern world would also not appear until the end of the Gothic period.

More Romanesque Nativity scenes

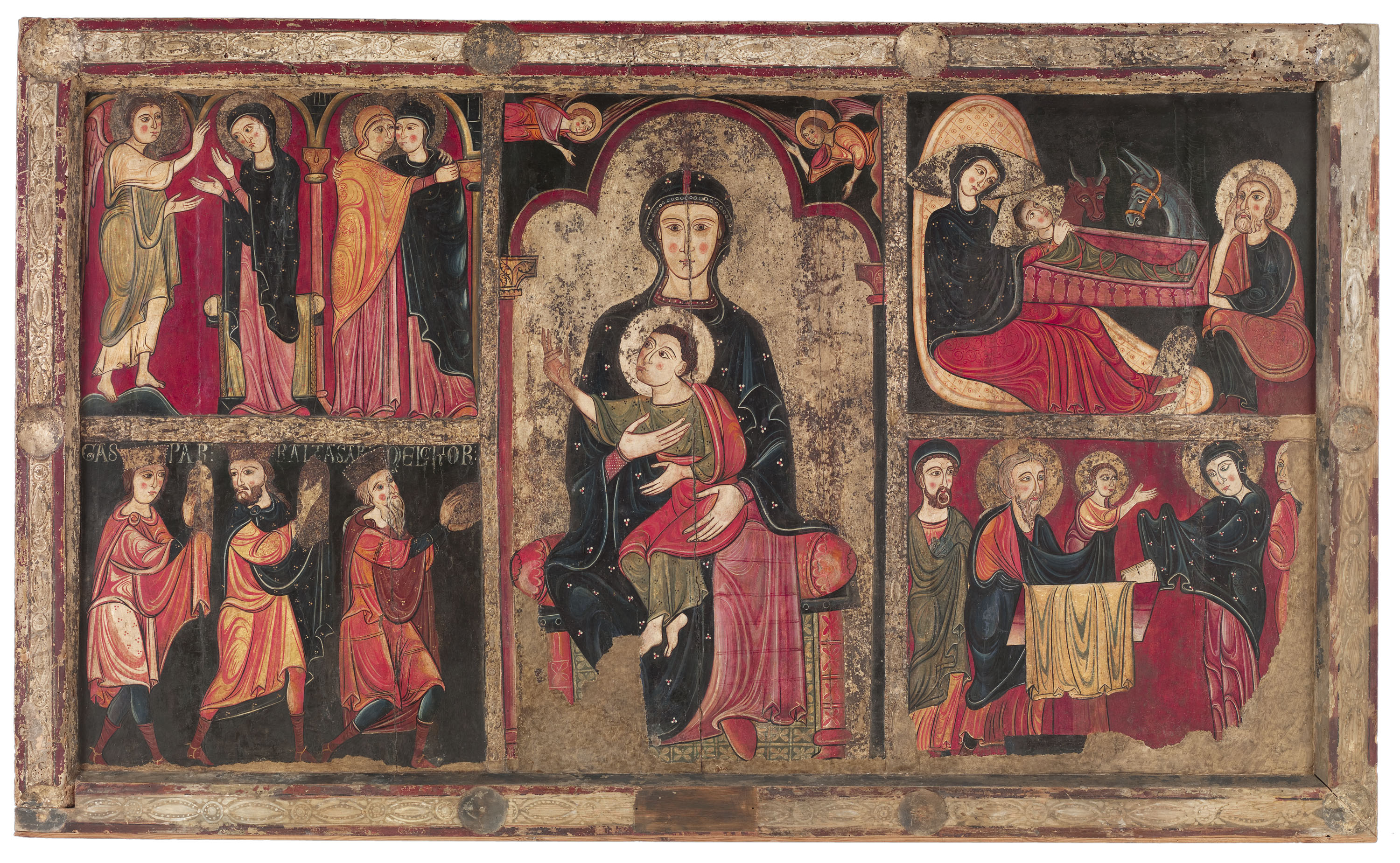

Anonymous, Altar frontal from Avià, circa 1200

Apart from the Birth of Sorpe, in the collection of the Romanesque Art of the Museu Nacional two more nativity scenes are worth highlighting: the altar frontal of Avià and the altar frontal of Cardet. In these two works, painted in the 13th century, Mary is still represented stretched out or lying down. In both cases, in addition, the Virgin can be found inscribed in a kind of bubble, yellow in Avià and black in the case of Cardet, which could be an abstract and symbolic representation of the cave in which Mary gave birth, according to the apocryphal gospels. The characters of the two midwives, however, have disappeared.

Iohannes. Taller de la Ribagorça, Altar frontal from Cardet, second half of 13th century

In the altar frontal of Cardet, at a later stage, we can see in the compartment where the birth scene appears that the representation of the announcement to shepherds was also included. These two Christmas episodes, closely linked to the narration done by the Gospel of Luke, would almost always be represented in medieval Catalan art from then on, to the point that it is very difficult to find a Nativity scene where only the Holy Family appears, without the shepherds, or a scene of the Announcement to the shepherds separately. One of the few solitary representations of this miraculous appearance is preserved precisely in the Museu Nacional, in a beautiful scene attributed to the Master of Vallbona de les Monges.

Master of Vallbona de les Monges, Announcement to the Shepherds and Annunciation, 1335-1350

Christmas in Gothic painting

In the Gothic Art collection of the Museu Nacional we can find two different models of Nativity scene, which are also the two most common ways of representing the birth of Jesus in Catalan art from the 14th and 15th centuries. The first model is the one we have seen in the Frontal of Cardet, where a representation of the Birth of Jesus is combined with the scene of the Announcement to the Shepherds. It is the scheme that we can see at the Nativity scene painted by Guerau Gener and Lluís Borrassà for the altarpiece of the monastery of Santes Creus, surely one of the most beautiful Christmas scenes that we can find in the museum. This splendid Gothic altarpiece is full of curious details, such as angels repairing the holes of the roof of the stable or the gloves worn by the shepherds to protect themselves from the cold of winter.

Guerau Gener, Nativity, 1407-1411

We can also find the same type of Nativity scene on a altarpiece sculpted in stone by the Master of Albesa for the crypt of the collegiate church of Sant Pere d’Àger.

Master of Albesa, Nativity, second half of 14th century

The other model of the Birth of Christ that we can find in the Gothic art rooms of the museum appears later in Catalan art, from the second half of the 14th century onwards. It is the representation of the Adoration of the Shepherds, an episode that is narrated in the Gospel of Luke just after the angel’s announcement and which allowed Gothic artists to unite the Holy Family and the shepherds in a single scene together. This allowed more coherence and monumentality to be given to the representation of the Nativity. In the museum we can find three examples of this Adoration of the shepherds. Two are linked to the workshop of the Sierra Brothers and offer very similar solutions: on the one hand, the isolated table that has recently entered the museum thanks to the Donation of Gallardo and that you can see at the beginning of this text, and on the other hand, the compartment of a major Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary attributed to Jaume Serra from the monastery of Sigena. The third altarpiece with the Adoration of the Shepherds is a Nativity scene from the late 15th century linked to the Lleida workshop of Pere Garcia de Benavarri.

Jaume Serra, Altarpiece of the Virgin, circa 1367-1381

In spite of the differences that can be observed between them, all three images have a similar composition: the boy Jesus is at the centre of the scene and the rest of the characters are spread around him kneeling and with gestures of adoration. Among them there are two or three shepherds, on the one hand, and the Holy Family, on the other.

Taller de Pere Garcia de Benavarri, Nativity, circa 1475

Seeing these compartments, we can conclude that the change which the Nativity scene from Romanesque to Gothic underwent is remarkable and especially significant in the case of the figure of the Virgin Mary, which has gone from lying down to recover from the effort of childbirth to kneeling beside the rest of the characters with a calm expression and great inner peace. This evolution is not by chance, but is the result of the intense theological debates that took place around the Birth of Jesus. During the Gothic period, doctors of the Church had already reached an agreement that the birth of Christ, being the son of God, had been clean and painless. Therefore, it was not necessary for Mary lie down and rest, nor for the midwives to assist the Virgin and wash the child. These two female assistants, however, would not end up disappearing completely until the Council of Trent, which prohibited their representation. In the two scenes of the Museu Nacional painted by the Serra brothers we can still find one of the two midwives, Salomé, next to the figure of the Virgin Mary.

On the other hand, in all the Births of Jesus that we can see in the Gothic Art collection of the Museum the ox and the mule always appear, two figures of enormous popularity in the nativity scenes that do not emerge from popular tradition but also originate, once again, in the apocryphal gospels.

The mysterious “wise men of the Orient”

And the Three Kings from the Orient? Keep clam, we haven’t forgotten them. As we said at the beginning, their story is narrated in great detail in the Gospel of Matthew, in such a way that in this case the apocryphal texts do not tell us anything new and would not be relevant in their representation. Even so, the New Testament does not say that there were three, nor that they were kings, or that they were magicians: they only talk about “Wise men of the Orient”. Therefore, the image we have today of these characters is the result of a long evolutionary process promoted by the Church and popular tradition.

Mosaic of the Holy Martyrs and the Holy Verges (detail). Basilica of St. Apollinar the New. Mid sixth century Source: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

The first thing that was specified was the number of «wise men of the Orient». In the older Christian representations, the kings used to be two, four or even twelve, as in the church of Syria. But since the gospels do clearly speak of three gifts, “gold, frankincense, and myrrh,” agreement was finally reached that there were three wise men. Initially they were not either kings or magicians, only wise men. In the Greek translation of the Bible, however, a term was used, magos, which can mean either wise men or magicians. Many theologians interpreted this term in the magical sense and thus it has remained in many cultures. But the Church, aware of the malicious and negative image that magic usually had, promoted its identification as kings, a condition that would not be fully consolidated in art until the year 1000, approximately. For this reason, in many ancient representations, as in the mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nouvo of Ravenna, the kings did not wear crowns but a kind of cap. This was a phrygian cap, a type of hood that from the classic Greek era was considered a typical hat of the Eastern peoples.

Master of Santa Maria de Taüll. Apse of Santa Maria de Taüll (detail), circa 1123

In the different representations of the three Kings we find in the medieval collections of the Museu Nacional, the “wise men of the Orient” already take on the characteristics that will single them out during the Romanesque and Gothic centuries. The paintings of the apse of Santa Maria de Taüll, dated around 1123, they are one of the first representations that we conserve. The three characters already appear perfectly dressed as monarchs, with rich crowns full of precious stones, and are accompanied by inscriptions that identify them without any doubt as Melchior, Gaspar and Balthazar, three names that would not be established in Western Europe until the 8th century.

The Epiphany or Adoration of the Kings was a very important event for the Catholic Church because it meant the recognition of the divinity of Christ by all the peoples of the earth. As representatives of all humanity, from Romanesque art the three kings would appear characterized as figurations of the three ages of mankind. Thus, as we can see in the paintings of Taüll, Melchior symbolizes old age, with white hair and a long beard. Gaspar, beardless, represents youth. And Balthazar, with his hair and beard still coloured, represents middle age. This characterization of the three wise men is the same as we can find in the frontals of Avià and Cardet that we have seen before.

Ferrer and Arnau Bassa. Annunciation and Three Kings of the Epiphany , circa 1347-1360

Passing from Romanesque to Gothic, the representation of the three kings hardly varies and would keep the features fixed in the previous centuries. In the scene of Epiphany, however, some new conventions would be incorporated, such as the gesture made by one or more kings, usually only Melchior, of leaving the crown at the feet of Jesus and kneeling before him as a symbol of submission, a position that clearly reminded us of the ceremony of oaths of fealty. We can see this, for example, in a fragment of an altarpiece painted by Ferrer and Arnau Bassa where we can see the three kings but we have lost the central image of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. In this scene we can see that the kings do not appear alone, but are accompanied by a page who keeps the mounts.

Jaume Huguet, Altarpiece of the Constable in the Palatine chapel of Santa Àgata (MUHBA). Photo: Amador Álvarez CC-BY-SA-3.0.

With the passing of the years, the role of the three kings on the Epiphany scene would be increasingly used as the perfect excuse for the representation of rich and luxurious clothes, jewellery and accessories, details that artists would take advantage of to exhibit all their virtuosity. In this sense, the Epiphany scene of the Altarpiece of Conestable, conserved in the chapel of Santa Àgata of Barcelona, is one of the most exuberant of Catalan Gothic.

Fernando Gallego, Epiphany, circa 1480-1490

As we can see, in the Altarpiece of the Conestable, King Balthazar is still white. In order to see a black king, one of the most significant and popular features of the current image of the “wise men of the Orient,” we would have to wait until almost the end of the Middle Ages: the first black Balthazar found in Catalan art dates from the last quarter of the 15th century. From this period, the Museu Nacional retains a beautiful Epiphany by the Castilian painter Fernando Gallego where we already saw a dark-skinned Balthazar and clearly African features.

Amics del Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya