Pablo José Alcover

and Rosa Mayordomo

Bread, a brief history

From prehistory to the Middle Ages, bread played a decisive role in food. So far, the oldest bread remains have been found in an excavation in Israel. They are 22,500 years old, that is to say, from the Upper Paleolithic period. These prehistoric loaves would be rounded, without yeast and flat. Visually they would remind us of the current pita bread from the shores of the Mediterranean, and the Maghreb, and that are now very popular in our country.

The ancient Phoenicians and Greeks also made bread similar to prehistoric ones. The consumption of Λαγάνα (“lagana” a Greek flatbread), unleavened traditional Greek bread, flat and with the surface decorated with sesame seeds, which would be documented from the 5th century BC.

There were many types of bread in Roman times. One of the most popular was the panisplebeius (“bread of the people”), which could include yeast, or not. Remains of popular Roman bread in good condition have been found in archaeological excavations in Italy. The study of these pieces has provided some data: they were about 20 cm in diameter, had a large volume and had a crust all over the surface. In addition, the top was scratched in the form of radii that formed portions. These facilitated the partitioning of the bread with the hands in as similar quantities as possible. One of the best preserved pieces of Roman bread today comes from the Pompeii site and is preserved in the Museum of Boscoreale.

In the Crown of Aragon, professor Antoni Riera estimates that an adult of the working classes ate between 400 and 700 grammes of bread daily. This daily bread was often round and did not have portions like in ancient Rome. This was because it was usually cut, as it is done today.

Medieval bread was a food with two realities: the everyday and the divine. We explain the first one in the introduction. The second is analysed later on.

The medieval preacher from Girona, the Francisan Francesc Eiximenis, describes in this way the diet of Catalans as himself: “contracten la carn ab les mans a cada vegada que·npreñen, e posenles davant en un poch de pa, e solament se’n hi posen un bocí, e han a posar la sal en altre poch de pa, e sullen lo pa e la tovalla per força en son menjar”. (loosely translated this meant, “they would pick up the meat, and each time they did so, they would be given a small piece of bread, they would forcibly soak the bread on a towel on their food ”) Therefore, a meal without bread was not understood.

Eiximenis also provides data that dismantles negative clichés of the Middle Ages: the “towel” was used. In fact, it was common to use a napkin on tables.

This is the fascinating and complex story of bread.

The representations of breads in a Gothic panel of the Museu Nacional

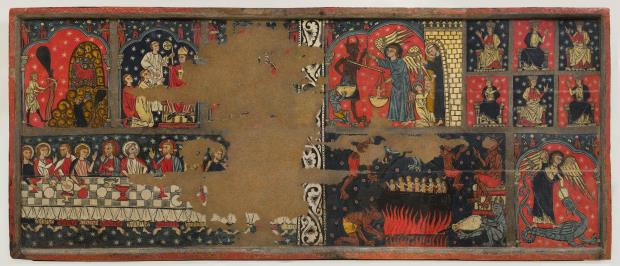

One of the Gothic panels of the Museu Nacional with a presence of bread is the Panel of Saint Michael, from the church of Sant Miquel de Soriguerola, dated to the last third of the 13th century. This work of art includes some of the most frequent scenes of the archangel St. Michael, such as the weighing of souls and the fight against the dragon. In addition, it highlights the Last Supper now detailed below.

The Last Supper is one of the most repeated episodes in Christian images since its inception because it expresses the institution of the Eucharist. Bread is essential to Eucharistic representations as it is a central element of it. In all cases, the loaves should be smooth (without yeast) because they were those of biblical Easter time.

There are several versions of the Last Supper in the Bible. The Gothic panel in the Museu Nacional seems to represent the version of the Gospel according to Saint John (Jn. 13: 21-30). Jesus was meeting with the apostles to celebrate the Passover when he announced that one of those present had betrayed him. Then “the disciples looked at one another, because they did not know who he was. One of the disciples, whom Jesus loved, was at the table beside him. Simon Peter signals to him because he asks him who he is talking about. He leans over Jesus’s chest and says, “Lord, who is it?” Jesus answers, “He is the one to whom I will give the piece of bread that I will now soak.” Then he soaked the bread and gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. At that moment, behind the piece of bread, Satan entered inside him. Jesus said to him, “What you are doing, do it quickly.” […] He took the loaf and went out at once. It was night. “

In the scene of the Last Supper of Soriguerola, the starry dark background could refer to it being night. The attendees are seated at the same table. They are all represented with a halo turning round their head, a symbol of holiness. The central character, Jesus, is the only one with a particular halo, called a crucifix, because it has a cross inscribed inside. There are no chairs represented. We can count 24 feet below the table. If initially the diners at the Supper were 12 apostles plus Jesus this adds up to 13. 24 feet represents 12 people. One is missing, who would it be? Possibly Judas, the traitor, who would have already left.

Most of the attendees look at each other and point to each other to see who the traitor was. Peter, sitting next to Jesus Christ, would be waving his hands to find out who the guilty one was. Unfortunately, the representation of the hands is not preserved. If so, we would probably see some fingers of Peter’s hand pointing at Christ.

Another version of this biblical episode can be found in the Gospel of St. Mark (Mark 14: 17-26). Here is more information about the food to celebrate the Passover: “While they were having supper, Jesus took the bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them. And he said, “Take it. This is my body.” Then he took a glass, said thanksgiving, gave it to them, and they all drank it. He said to them, “This is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for all.”

In the scene of Soriguerola we can see that Jesus makes the gesture of blessing with his hand. How do we know this? The two fingers, the little one and the ring finger, closed on the palm of the hand would refer to the double human and divine nature of Jesus, while the three outstretched fingers (thumb, forefinger and heart) would symbolize the Trinity. What is he blessing? Two foods mentioned in the Bible are on the table: bread and wine. Look at the loaves: they are round as the medieval ones usually were. The artist probably represents the most common form of bread in the 13th century to make it easier for the faithful to quickly identify this object on the table.

Therefore, the bread was also the body of Christ, one of the two substances of the Eucharist, as St. Mark’s version of the Last Supper points out. The divine side of the bread was one of the reasons that made him king at the panels of Christians, both in the Crown of Aragon and throughout Europe.

In the representations of the Last Supper of the time we also find this round shape of the bread. Three examples: a mosaic of the Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice, a mural of the old chapel of Santa Catalina of la Seu d’Urgell Cathedral and a Florentine panel preserved in the Little Palace Museum of Avignon.

Otherwise, in these three works we can observe the presence of knives and sliced round loaves that represent the communion of the apostles who eat the bread / body of Jesus. In the case of the mural painting of La Seu d’Urgell we see how Judas Iscariot, separated from the rest of the apostles, eats the piece of bread dipped by the hand of Christ.

Here ends our journey through the art of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya and the history of bread.

Let’s eat bread. As they say in Menorca: “a casa sense pa, a juliol fa fred” (At home without bread, it’s cold in July).

Question: Why do fish appear on the Panel of Saint Michael and on the mural in the old chapel of Santa Catalina in the Cathedral of La Seu d’Urgell? We will find out in a future post.

Pablo José Alcover

and Rosa Mayordomo

Dr. Pablo José Alcover Cateura and Rosa Mayordomo i García are food historians. Dr. Pablo José Alcover Cateura is a researcher at the Food Observatory (ODELA), a consolidated research group at the University of Barcelona. His research revolves around medieval food (12th-15th centuries) in the Crown of Aragon. His thesis is the first study of the “mostassaf”, a medieval official who acted as a defender of the current consumer, which has as his space all the kingdoms and territories of the Crown of Aragon and the period of time the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Rosa Mayordomo i García is an academic at the Catalan Academy of Gastronomy and Nutrition (ACGN). She obtained the “Research Sufficiency” with the thesis “Textile Symbology in the Tiwantisuyu” focused on pre-Hispanic research. She is currently working on her doctoral thesis in Food History on the introduction of corn in the Iberian Peninsula and its expansion into the territories of the Spanish Monarchy (14th-18th centuries). This thesis is directed by the professor of Modern History, María de los Ángeles Pérez Samper.

E-mails: Pablo José Alcover Cateura [email protected] and Rosa Mayordomo García [email protected]