Montse Frisach

In recent years, archives have taken on a predominant role in contemporary artistic practices. Many artists often work with archive materials or even with the idea of the archive as the central argument of their works. Furthermore, museums and artistic institutions have also become aware that their archives should not just be simple deposits and repositories of documents but that their activation, whether by curators, researchers, artists or the archivists themselves, generates new knowledge and cross-cutting semantic relations that broaden the vision that existed until now about these spaces. Institutions are also increasingly questioning how to bring all these activations of the archives to their visitors through exhibitions, so that the exhibition is not just a simple set of papers locked in glass display cases. Archives, therefore, have ceased to be passive storage spaces, but are now understood as sets of living documents, fully integrated into the dynamics of artistic institutions.

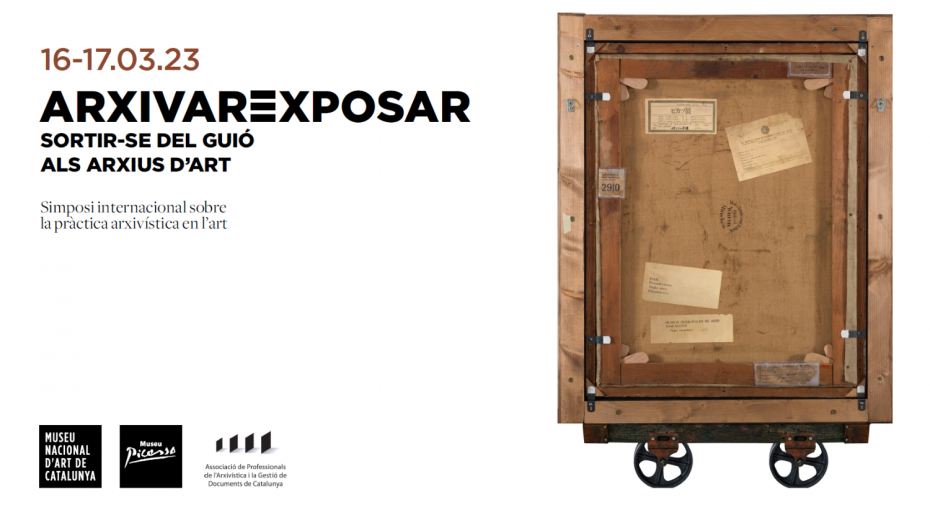

This was the theme of the international symposium Archiving. Exhibiting. Going off script in art archives, organised thanks to the alliance between the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC) and the Museu Picasso of Barcelona and which took place on 16th and 17th March at their two venues. The symposium had a totally interdisciplinary approach and brought together archival experts, curators, artists, historians and researchers from all over the world who highlighted the importance of archives as living and dynamic organisms and where the boundaries are increasingly being diluted between the tasks of some professionals and others.

The title of the symposium also alludes to the theme that in this new and changing perspective, there is a constant mutual exchange on how to archive and how to exhibit. Therefore, today it is impossible to disentangle art from archives. A theme that was present throughout the two days of the symposium, which was very well received by the public, with 400 registrants, both in person and online.

On the first day, which took place at the Museu Picasso, Eric Ketelarr, emeritus professor of Archives at the Universiteit van Amsterdam, was in charge of opening the symposium with a talk on the relationship between artists and archivists. Ketelarr noted that “in contemporary art, the archive has become the dominant cultural form”. When the artists approach the archives, they highlight the fact that the act of storage itself, marked by the rules of archival practice, is absolutely arbitrary: “Rearranging becomes an interpretative and creative act”. The archive, therefore, should never be seen as something “static” since subjective decisions about how things are archived generate different results and condition the future. “Archives are not so much to do with the past as with the future”, stated Ketelarr. Today, immersed in the complexity of the digital world, the dilemma is to decide which items on the network need to be dispensed with, destroyed or transferred to another system.

The major challenges of technological change for archives was precisely the topic of the intervention by Laura Millar, independent consultant in documentation, archives and information management. At a time when the circulation of fake news is the order of the day, archivists, who traditionally assumed the role of collecting authentic evidence of historical events and facts or documenting the authenticity of a work of art, now have to make decisions more actively so as to preserve “the truth”. One of the urgent needs of the digital world is to protect and validate authenticity so that repositories are reliable. In this sense, the work of the archivist is being transformed at high speed and, according to Millar, frequent collaboration with experts in other fields such as technology, deontology and legal aspects is necessary. The job of the archivist, therefore, must be to “facilitate reliable evidence so that everyone can use it at the service of the truth”.

Some participants in the symposium described some practical cases of activation of both historical and artistic archives in museums, which have played a reparative role. The archivist and historian Michael Karabinos who has recently devoted himself to research in colonial archives, focused his intervention on how art and design museums can reactivate historical archives with examples that have expanded the narratives of museums in the Netherlands. In the Van Abbe museum of Eindhoven, an art museum founded thanks to the donation of a cigarette manufacturer in the 1930s, Karabinos investigated the family and business archive kept by the grandson of the founder. In this way, he was able to connect the cigarette company’s colonial past and integrate this history into the museum’s permanent collection. With this new information, which had remained hidden until now, the archive has served to shed light on a past that now acts as a “restorative force”.

Beatrice von Bismarck, professor of art history and visual culture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig, referred in her presentation to the way archives open up to new narratives from the moment they are involved in an exhibition. She cited some examples of how artists also use archives to develop critical analysis of the construction of history. One of them is the installation that the French Canadian artist Kapwani Kiwanga put on at the South London Gallery in 2015, in which, through archival material, fabrics and plants, she deconstructed the official version of two moments in the colonial history of present-day Tanzania.

With the same role of reparation and historical revision, the Portuguese artist Catarina Simão, explained her artistic and mediation project called Sala Colonial, still in process, based around a collection of 288 African objects belonging to the old Liceo Nacional de Lamego, which is now in the custody of the museum of this city in northern Portugal. The school and the students are involved in the project. The artefacts, poorly inventoried, devoid of information about their exact provenance, were exhibited for decades at the institute that owned the pieces in a room where they were used for educational purposes but with a marked colonial ideology. “What we intend with the project is to deactivate objects that were used for colonial propaganda”, said the artist.

Archives with an artistic theme can also be central protagonists of exhibitions, Debora Rossi, head of the historical archive of contemporary arts of the Biennale di Venezia explained how the immense documentary legacy of the event, in all its branches, has become the basis of activities, research projects and exhibitions. In fact, the archive is called the “seventh muse” of the Biennale. The activity that marked a turning point in the use of the archive was the special exhibition The disquieted muses. When the Biennale di Venezia meets history., which was organised in 2020 to replace the cancellation of the event’s activities due to the pandemic. Instead, all sections of the Biennale came together for the first time to build a single exhibition on the history of the event, based on materials from the archive.

The two museums organising the symposium also shared recent exhibition experiences about their own archives. Sílvia Domènech, Head of the Museu Picasso’s Knowledge and Research Centre, and Núria Solé, the museum’s archivist, explained how the exhibition about the Brigitte Baer archive was created, specialist in the graphic work of Picasso, which took place in the summer of 2022. Since 2011, when the exhibition Picasso 1936 was organised, the museum considers that “documentation is also part of the language of art”. In this sense, Brigitte Baer’s archive, which entered the museum thanks to the donation of the expert’s nephew, David Leclerc, is a fundamental source for the museum. Baer was in charge of completing the catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s graphic work when only two volumes, drawn up by Bernhard Geiser, had been published. She inherited Geiser’s documentary material, completed it and finished the catalogue with up to seven volumes. In the Museu Picasso, Baer’s archive, constituted as an essential corpus for the study of Picasso’s engravings, has been organised as in a “sediment of strata”, in a division by eras, from Geiser’s working materials until the final era when Baer continued to add information to her worksheets after the publication of the catalogue, so that one can follow the journey through time to complete a huge scientific task.

In the MNAC, on the other hand, the exhibition Anglada Camarasa. The premeditated archive, from 9th February to 7th May, 2023, is dedicated to the archive that the painter built up throughout her life and that was donated to the museum in 2020 by her daughter Beatriz. As the title of the exhibition makes clear and Pilar Cuerva, head of the Research and Knowledge Centre of the MNAC, explained already at Friday’s session at the museum of Montjuïc, this is an archive with a consciousness of lasting on the part of Anglada Camarasa herself, who devoted herself to diligently saving material about her life and work, from her birth certificate to press dossiers, personal documents, catalogues, scrapbooks, photographs and notebooks.

Fortunately, the artist’s daughter has taken charge of all the material with great dedication and care, which has made it possible for the archive to be in very good condition. This can be seen in the exhibition which, curated by Cuerva herself and Eduard Vallès, recreates in its museography the aspect of an archive. “We were clear that we wanted to museograph the archive, but without it becoming a theme park or boring”, explained Cuerva.

The second session of the symposium opened with a more general presentation on the profession of archivist with a contemporary archival history in Catalonia, Ramon Alberch, currently Coordinator of the Cultural Dynamization Work Group of the Archives of the Association of Latin-American Archivists (ALA-GTDCA). Alberch referred to the “polyhedral archives”, in the sense that the plurality of contents that treasure the archives and the diverse views of the researchers give rise to equally plural interpretations. Alberch gave a dynamic vision of the profession and the archives, far from the historical visions and clichés that have spread literary and cinematographic fictions, giving the archives attributes of power, mystery, nocturnality or secrecy. Instead, he referred to current realities and dilemmas about whether or not to keep social networks, with the cost of preserving digital memory or about the need or not to archive documents considered “insignificant”, which sometimes can become keys to solving court cases or denouncing political and social injustices. As there is no such thing as an innocent or objective archive, Alberch believes that archives must go beyond the intention of preserving “officialist” history and emphasised the importance of “social archives”.

For his part, PhilippeArtières, history researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, of France, also emphasised during his intervention the dynamic and social nature of archives, as “living objects that we manipulate”. In his own practice as a researcher and biographer, Artières defended the recovery of stories through almost domestic materials such as the practice of scrapbooking or even tattoos, which are like an autobiography written on the body. In an extended vision of the archive, he himself incorporates performance practices into his research method. Thus, to investigate what had happened to a relative of his mother, the Jesuit, Paul Gény, murdered in 1925 in the streets of Rome, he lived in the city for five days dressed in a cassock in a kind of character reconstruction. In 2017 Artières also personally collected people’s memories about the Centre Pompidou, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the institution, in an “Office of Popular Archives” that the visitors found at the entrances to the centre. “The archives are now outside their walls thanks to the artists”, he concluded.

Precisely, an artist and writer such as Perejaume contributed to the symposium a critique-poetic reading, entitled La vida de les obres (The life of the works), around the accumulation of works of art, which in a way was a provocative counterpoint to everything that had been said at the symposium up to that point. In his text, Perejaume questioned to what extent it is worth keeping all the works of art that are generated and have been generated in the world. “The collective effort for the accommodation and permanence of the works is huge and the number tends to infinity. All the works that we intend to bring to life is overwhelming”, he said. All this when it turns out that everything is destined to disappear. The desire to last beyond the death of the artists, however, is too powerful. On the other hand, Perejaume praised loss as another expressive element: “The perfume of flowers is the putrefaction of the petals”. The artist sees in loss, a gain, and that perhaps there are works made for memory and works made for oblivion. Paradoxically, he himself is also ordering and spreading through the network an archive of his work, but for him “the model is not one of accumulation because the world is also a dumping ground for culture and culture also pollutes”.

Ernst van Alphen, professor emeritus of the University of Leiden, made a defence of artistic archives because they “overcome the contradictions of the official archive”. Van Alphen cited some examples of artists who have used their own and others’ archives to build open and restorative narratives. In the case of many current artist books, the format is usually archival. For example, the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng collected photographs, in the book the Black Photo Album, of black middle-class families, taken between 1890 and 1950. The artist Inge Meijer collected photographs and documents about the plants that decorated the exhibition rooms of the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam from 1945 to 1983 in the book The Plant Collection, with an also archival format and which constituted a research, on the one hand, about botany, and on the other hand, about part of the buried history of the museum. Likewise the photographer Mathieu Pernot has compiled the photographic history of French gypsy families and Pablo Lerma “inspects the homogenising effects of the archive” in a compilation of images about the stereotypes of gay culture, including photos that break away from with these stereotypes.

The last presentation of the symposium presented a research on the presence of documents in the paintings of the National Gallery of London which was carried out expressly for this conference by the professor of the Faculty of Documentation and Communication Sciences of the Universidad de Extremadura, José Luis Bonal. In the online collection of the London art gallery, Bonal found, among 2,600 paintings from the 14th to the 19th centuries, 226 works in which documents appear and has classified them by genre, also studying the role that the document played in the scene. Eighty percent of the paintings with documents are from the 15th to the 17th centuries, especially religious paintings, those of the traditional genre and portraits. The functions of the document in the scene are very diverse, from identifying the person or people portrayed to conveying a message, through the appearance of scores in musical scenes, commercial documents or papers on which the artist signs. Bonal’s research, in addition to having a component of fun, is a good exercise that helps to look at the paintings in a museum in a different way and at the same time emphasises the importance of the document throughout history, seen through artworks.

The closing of the symposium offered a live example of the direct relationship between archives and contemporary artistic practices with the performance entitled Into Sugar we could have turned), by Mireia c. Saladrigues, which took place in the MNAC’s Oval Room. The action is related to the research that Saladrigues carried out for her doctoral thesis on the attack on the finger of Michelangelo’s David, which took place in 1991. Based on her research in the police and judicial archives, documents on the restoration of the work, press articles and even with an interview with the aggressor, Piero Cannata, Saladrigues activated some of the documents used during her research, with interpretations and representations of that iconoclastic event and gave voice to the dust generated by the hammering on the iconic sculpture. It was a poetic closure to two days, which in the future will have a publication that will gather together the entire symposium.