Montse Gumà

Saint Michael

Up to now I have mentioned few names because, of all these celestial creatures, the only ones that have one are the archangels, a class apart among the celestial cohorts and, from the point of view of the iconography, the richest. Although there are seven of them, a sacred number, there are four whose names coincide in the different sources, Michael, Gabriel, Raphael and Uriel, and three that vary, but which according to Orthodox tradition are called Barachiel, Jehudiel and Selaphiel. Of the seven, in 746 the Lateran Council limited worship to the first three. And it is these three to whom important feats are attributed in the story of the Salvation, and who have a varied iconography associated with their acts, especially Saint Michael, the one with the most clearly defined personality.

Altar frontal of the Archangels, second quarter of the 13th century

Four episodes are depicted on this altar frontal in which these three archangels are the protagonists, Michael especially. In the first of the four compartments, Raphael and Gabriel carry the soul of a dead man, naked and sexless, wrapped in a white sheet, up to Heaven. In the compartment next to it Michael, armed with lance and shield, fights the dragon, the embodiment of the devil, whom he will defeat. In one of the other compartments Saint Michael weighs the good and bad acts while a black demon tries to cheat, and in another the miracle of Mount Gargano appears, in which the archangel appears to a hunter in the form of a bull. The hunter’s arrow doubles back on its course and comes back to hit him in the eye, to clearly show Michael’s wish that a sanctuary be built to him on this Italian mountain. In the battle with the dragon, the weighing of the souls and the apparitions on Mount Gargano, Mont Saint-Michel and in Hadrian’s mausoleum in Rome, these are the most frequently depicted iconographic themes associated with Saint Michael.

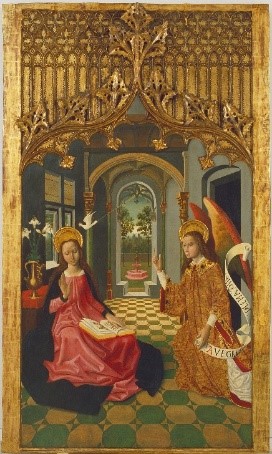

Joan Mates, Altarpiece of Saint Michael the Archangel, first quarter of the 15th century

On this altarpiece, dedicated exclusively to Saint Michael, we are immediately surprised by the archangel’s appearance. In earlier depictions, as we have seen up to now, like his companions Gabriel and Raphael he wears a tunic or dalmatic. But here his dress has changed and he appears as a medieval warrior-knight, clad in armour and armed with a lance. With regard to the scenes in which he appears, in the one in the middle he fights the dragon, in this case a seven-headed monster. On the right, two episodes that we already know: the miracle of Mount Gargano and, below it, the weighing of the good and the bad acts of the dead. On the left we see the fall of the rebellious angels, Saint Michael fighting once again, leading the divine armies against the rebellious angels, shown with zoomorphic forms, and the subsequent division between Heaven and Hell. At the top, and on either side of the Crucifixion scene, an Annunciation with the archangel Gabriel as the protagonist, whose appearance is nothing like that of the prince of angels.

I shall now show you different examples from the collection, from different periods, in which Saint Michael fights the dragon and emerges victorious. The dragon’s presence sometimes has to be sensed, as it is not explicit. We shall see him dressed in a tunic or dalmatic, as a medieval knight, and from the Renaissance onwards as a Roman general, but always armed with a lance and fighting against evil.

As we have already seen in the Frontal of the Archangels, Saint Michael is also the protagonist of the scene of the weighing of souls, where he appears weighing a soul on some scales while a devil tries to cheat, tugging at the scales to tip them towards his side. It is an episode that is often shown in depictions of the Day of Judgement, as in the paintings from Santa Maria de Taüll, although, as in the case of the altarpiece by Joan Mates that I commented upon, it accompanies a Mass in aid of the living to rescue souls from purgatory.

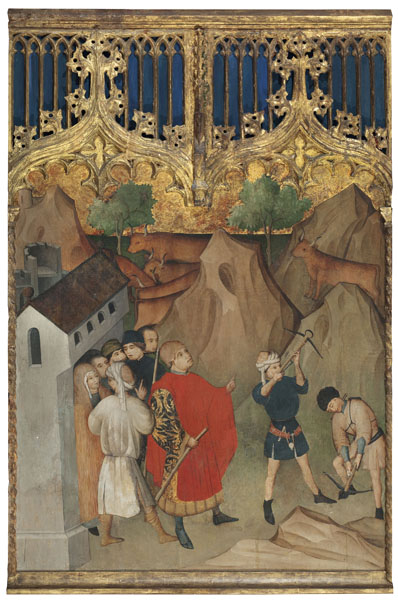

I have already said that according to Christian tradition Michael appeared on Mount Gargano, one of the most famous miracles of all those attributed to him. In this fifteenth-century panel, a group of figures has just seen the shepherd Gargano shooting with a crossbow at the bull that has strayed from its herd, and the bolt has miraculously turned round and hit the crossbowman in the eye. Due to the bewilderment caused by what has just happened, Saint Michael eventually appears and announces that this miraculous event is his work, and that he wants a sanctuary dedicated to him to be built in this place, a wish that is fulfilled. Despite being a recurrent theme in Gothic art, in the museum we can find two of the earliest depictions of it in Catalonia to be conserved: the Frontal of the Archangels and the Panel of Soriguerola.

Nicolás Francés, The Miracle of Mount Gargano, about 1440-1450. On permanent loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya, Gallardo donation, 2015

Master of Soriguerola, Panel of Saint Michael, late 13th century

Saint Gabriel

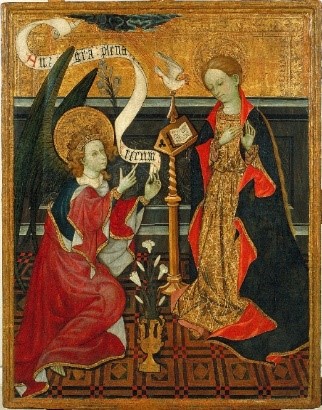

With regard to Saint Gabriel, up to now we have found him as the advocate of the Day of Judgement next to Michael and Raphael in Romanesque paintings, and accompanying a dead soul to Paradise, along with Raphael, in the Frontal of the Archangels. However, in his capacity as God’s messenger archangel he is one of the principal actors in the scenes of the Annunciation to Mary. In this respect, although he is shown many times, because he appears in all the Annunciations, his iconography is not as varied as that of Saint Michael. He is depicted as a winged figure, young and often androgynous, dressed in an alb or dalmatic, holding a sceptre in his hand.

Altar frontal from Mosoll, first third of the 13th century

The sceptre is often replaced by a white lily, the symbol of the purity of the Virgin Mary. Although he normally holds it in his hand and offers it to Mary, the flowers may also appear in a vase in some part of the scene, set in an interior that we could call domestic. On other occasions the lily is added to the sceptre.

Apart from the lily, Gabriel may hold a phylactery or sign on which is written his greeting to Mary at the time of the Annunciation: Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum, or “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee”. It can be seen in this anonymous early fifteenth-century painting from Valencia, on the sixteenth-century bride’s chest, or on the two previous panels of the same scene.

The hands are usually in a position of greeting, although he sometimes points up towards heaven with his finger, indicating that he is carrying out a divine order. He also appears with his hands crossed over his chest as a sign of respect.

Gabriel is also the protagonist of other scenes, which are however not as popular as the Annunciation to Mary. In the case I shall now show you, also as God’s messenger he was given the task of announcing to Zacharias, while he was officiating a mass, that his wife Elisabeth was pregnant and that she would be the mother of Saint John the Baptist. We can see this in a scene from Santa Maria de Taüll, in the top right-hand compartment of the Altarpiece of the Saints John by the Master of Santa Coloma de Queralt, and in the drawing by Josep Bernat Flaugier that you see here.

Saint Raphael

As with Gabriel, we have seen Saint Raphael as the advocate of the Day of Judgement in Romanesque paintings and accompanying a dead soul to Paradise on the Frontal of the Archangels. But the story that is associated with Raphael, in which he is one of the main characters, is the one about Tobias and his pilgrimage in search of a pious wife. Raphael, sent by God, accompanies the young man on his journey and helps him achieve his goal. The archangel, sometimes wearing a tunic or dalmatic, at others dressed as a pilgrim, tells Tobias to catch a fish and to remove its entrails and burn them. This will help him to scare off the devil that is in love with the young man’s bride-to-be, and it will break the spell that makes the girl a widow every time she marries. As well as this Tobias heals his blind father, using the bile of the fish. This is why Raphael often appears also with a fish or with a pot of ointments and remedies.

It is the story of an angel doctor, who heals the father’s blindness, and at the same time a guardian angel who accompanies and guides young Tobias, but it may also be that of an archangel sacrificed in artistic depictions, because painting three archangels breaks the symmetry of the scene. If you remember – going back to the beginning – in the paintings from Àneu, while Michael and Gabriel appear on the apse ceiling, Raphael is relegated to the intermediate register next to the seraphim. It is also a fact that his cult was not as popular as that of Saint Michael and that the life of Tobias was not painted as much as the Annunciation to Mary.

Francesc Pla Duran, el Vigatà, Tobias, the Archangel Raphael and the Dog Come to the River Where he has to Wash his Feet, between 1780-1784

After reading this article, you will have learnt to identify some angels through certain elements that appear associated with their depiction and you will even understand and be able to tell some of the stories expressed in the works of art. If you are interested in the subject don’t miss the virtual route Who is who, where we show you other saints and the attributes that identify them.

Related links:

Not all angels are the same: art shows us this / 1

Projectes digitals